|

Cartoons of

Dan McConnell

featuring

Tiny the Worm

Cartoons of

David Logan

The People's Comic

Cartoons of

John Jonik

Inking Truth to Power

|

Support the WA Free Press. Community journalism needs your readership and support. Please subscribe and/or donate.

posted Nov. 4, 2009

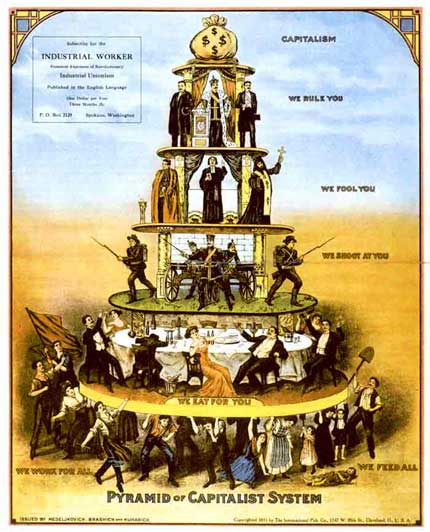

An IWW poster, published in Spokane

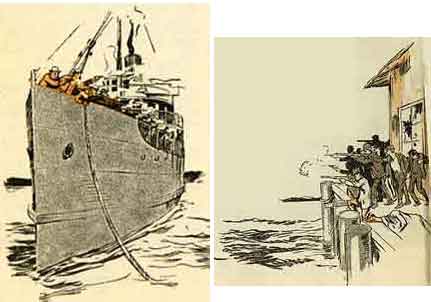

An illustration of the events of the Everett massacre. Wobblies are on the ferry Verona as deputized vigilantes fire from the shore.

The Everett, WA dock where the 1916 massacre of IWW members occurred.![]()

FANNING THE FLAMES OF DISCONTENT

Part 2: Free Speech Fights in Fresno, Aberdeen, San Diego and Everett

By Dale Raugust

Part 1 of this series (wafreepress.org/article/090903history.shtml) focused on the Spokane Free Speech Fight of 1909-1910, one of the most dramatic ideological battles fought by the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW, also known as the “Wobblies”).

The battle was essentially against the banning of labor rallies by local governments. Despite Spokane’s use of mass jailings and torture, the Wobblies, assisted by the famous agitator Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, ultimately succeeded in securing the right to assemble and organize there. But similar battles loomed ahead in both Washington and California.

The IWW and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn went to other cities after Spokane to engage in similar fights for free speech and the right to organize the workers. In Washington State, Wenatchee and Walla Walla had free speech fights in 1910, which were also victories for the IWW.

In Fresno, California, the IWW opened a union hall, Local 66, in November, 1909, about the same time that the Spokane fight was kicking into high gear. Fresno is in the heart of the San Joaquin Valley, the fruit capital of California. Men also came to Fresno to look for work in the construction and railroad fields. Within a short time the Mexican workers on a dam project had been organized and railroad workers were on strike under Local 66’s leadership. Local officials demanded that the city do something to stop the IWW from organizing.

As had happened in Spokane and other cities, Fresno officials responded by passing a ban on street speaking. Once again the Salvation Army and other religious groups were exempted from the ban. After the conclusion of the Spokane fight veterans like Frank Little came to Fresno. The fight started on August 20, 1910 with the arrest of Little. The example of Spokane was followed with the telegraphing of calls for help to every IWW Local. Thousands of men prepared to travel to Fresno.

"WE RULE YOU, WE FOOL YOU, WE SHOOT AT YOU, WE EAT FOR YOU, WE FEED ALL, WE WORK FOR ALL"

The free speech fights soon evolved into a struggle between IWW workers and vigilantes. Fresno was the beginning of significant vigilante action. On December 9, 1910, about 1,000 vigilantes attacked a group of Wobblies and onlookers attending a street speech. Several men were severely beaten. The vigilantes then advanced on the IWW headquarters, an open-air tent that was being used because the IWW had been evicted from their regular headquarters. The tent was burned down along with supplies. The vigilantes then marched to the county jail, where about 50 street speakers were incarcerated, and threatened to lynch the prisoners. Fortunately the vigilantes back off.

The jailed Wobblies received treatment similar to that in Spokane. The diet was bread and water and the prisoners went on frequent hunger strikes. The fire hose was turned on the prisoners until they were standing knee deep in water. Beating and injuries were common. The call went out for more men to come to Fresno. Rumors began to circulate among city officials that as many as 5,000 Wobblies were on their way to Fresno.

With jails already full and the mounting cost of the battle, Fresno leaders met and decided to bring an end to the fight. Mediators were hired on February 22, 1911, to settle the dispute. The prisoners had just two demands: a parole for all prisoners and the repeal of the ordinance against street speaking. After a three-day debate among city officials the demands were granted in their entirety.

New Anti-Wobbly Tactics in Aberdeen

Aberdeen, Washington was the center of the western Washington lumber industry belonging to Frederick Weyerhaeuser. Vigilantes played a role in cities like Fresno, but until Aberdeen it was an unauthorized role.

Two new tactics to counter the IWW were invented in Aberdeen: the deputizing of local residents as police to counter the IWW, and the organized “deporting” of IWW members.

In anticipation that the IWW would try to organize the lumber workers, the Aberdeen City Council passed an ordinance prohibiting street speaking or assembly by the IWW. The ordinance was unusual in that it specifically named the IWW. The ordinance did not apply to any other organization. This took away the support of the Socialist Party and other organizations that were not subject to the ban.

The fight began on November 22, 1911, with the arrest of five men. More than five hundred of the city’s “prominent and professional men” were organized into a vigilante committee, deputized by the chief of police, and given the task of escorting the arrested speakers to jail. The vigilantes were armed with “wagon spokes and axe handles for use as clubs,” and under the protection of the police the vigilantes broke the heads and limbs of many of the men escorted to jail.

With the jail full and the cost of jailing getting too great, the city decided to try a new tactic. In December 1911, the vigilantes were instructed to beat the arrested men and then escort them out of the city with a warning that their fate would be far worse if they returned and were again arrested. Then the vigilantes decided that there was no need to wait for a Wobbly to speak on the street before taking action against him.

Armies of deputized vigilantes patrolled the streets, ready to attack and deport any Wobblies. These deputies broke into outlying encampments where Wobblies were gathering, driving them out of the area. In the face of this lawless action the IWW gained support from moderate citizens of the community including the American Federation of Labor. A boycott of Aberdeen businesses put additional pressure on business and the city to end the fight. On January 7, 1912, the Aberdeen City Council repealed the street speaking ordinance and agreed to indemnify the IWW for damages to its headquarters.

Running the Gauntlet in San Diego

The free speech movement in San Diego during the winter and spring of 1911-1912, was one of the largest and included not just the Wobblies, but also socialists, anarchists, taxpayer rebels and others. For twenty years an area of San Diego known as “Soapbox Row,” on E Street between Fourth and Fifth, had been set aside for street speaking. In twenty years there had never been an incident of violence or riot.

The suggestion that “Soapbox Row” should be shut down came after the business interests in the city reacted with hysteria to the bombing of the office of the Los Angeles Times, and the confession on December 1, 1911, of two brothers, labor leaders, to this crime. The public’s reaction to the bombing and the confessions likely resulted in the loss by the socialist candidate of the mayoral race in Los Angeles, and halted union drives throughout the city.

San Diego business interests reacted to the bombing and confession by presenting a petition to city council demanding a street speaking ordinance. On January 8, 1912, the council passed a ban on all street speaking in San Diego, including Soapbox Row, citing traffic concerns as the reason. San Diego was not a place where there was a lot of radical labor activity, but once the ordinance was passed the San Diego Free Speech League was quickly formed to contest the law.

Unlike other cities which banned street speaking, San Diego’s ban included all organizations. As a consequence several religious groups joined in the protests. The San Diego Free Speech League included Wobblies, Socialists, tax protestors, religious organizations and others, with membership at about 2,000 and the ability to rally thousands more.

At first not much happened. The street-speaking ordinance was not enforced and was only occasionally deliberately disobeyed. The delay gave the city time to consider the use of vigilantes. As in Spokane, San Diego was serviced by four daily newspapers and a number of weekly papers. Two of the dailies, the San Diego Union and the San Diego Evening Tribune, were solidly anti-IWW. A third, the San Diego Sun, tried to remain neutral. The fourth, the San Diego Herald, printed the Wobblies’ side of the story until its editor was kidnapped and almost murdered, and its office destroyed.

The San Diego Union was the first to suggest that vigilantes be utilized to deal with the Wobblies: “I don’t believe that guns and bloodshed are necessary, Horsewhips are enough to deal with these fellows.”

Once the arrests started the jail filled up quickly. The treatment of the prisoners was similar to that which happened in Spokane. The San Diego Sun’s editor condemned the treatment of the prisoners: “Murderers, highwaymen, cut-throats of the blackest type, porch-climbers, burglars, wife-beaters and all kinds of criminals in jail in the past have been treated like royalty in comparison to the manner in which the street speakers are now being handled.” The Sun pointed out that the treatment of the prisoners “has done more to make this fight a nasty one than any other thing.”

from Sunset magazine, 1917

The reaction of the San Diego Free Speech League and the Wobblies to the treatment of the prisoners was to call out for more speakers. It was thought that thousands were on their way to San Diego. The city then took the advice of the editor of the Union by forming independent vigilante committees, which were given the authority to act outside the law and the promise that they would not be punished for their efforts against the street speakers. The vigilantes stopped the trains coming into town and pulled the men riding to the free speech demonstration off the trains. They were clubbed, beaten and forced to “run the gauntlet.”

According to one victim of the gauntlet: “The first thing on the program was to kiss the flag… when you kissed the flag you were told to run the gauntlet. Fifty men being on each side and each man being armed with a gun and a club and some had long whips. When I started to run the gauntlet the men were ready for action, they were in high spirits from booze. I got about 30 feet when I was suddenly struck across the knee… splitting my knee…. As I was lying there I saw other fellow workers… some were bleeding freely from cracked heads, others were knocked down to be made to get up again. Some tried to break the line only to be beaten back. It was the most cowardly and inhuman cracking of heads I ever witnessed.”

Once the gauntlet was run the men were thrown on wagons or boxcars heading out of town and told that if they came back they would be killed.

San Diego’s Chief of Police, J. Keno Wilson, was the leading figure in the drive against the Wobblies. It was he who ordered the conditions in the jail, deputized the vigilantes and gave them the authority to do whatever was necessary to “rid the city of beggars and crooks and the idle who don’t want to work.”

The Wobblies were seen as a threat to the peace of the city and a threat to the property interest of businessmen. They were characterized as lazy, opposed to the work ethic and a threat against decency and American values. By early March, 1912, hundreds of men were in jail and the vigilantes began to patrol all routes into the city. On March 22, midnight raids began on the jail and vigilante gauntlets were set up at every entry to the city.

On March 28, a 65-year-old Wobbly was held down and beaten in his testicles so severely that they ruptured causing his death. That same day the editor of the San Diego Herald was kidnapped and threatened with death. The vigilante committee issued a statement published in the San Diego Sun on April 12, 1912, “that hereafter they will not only be carried to the county line and dumped there, but we intend to leave our mark on them in the shape of tar well rubbed into their hair so that a shave will be necessary to remove it…” On April 22 dozens of “vagrants” were stripped, robbed, beaten, and forced to run a gantlet of 106 men.

At the urging of attorneys for the IWW, the Governor of California, Hiram Johnson, sent an investigator to San Diego. Colonel Harris Weinstock held open hearings from April 18 to 20, 1912. He also conducted his own independent investigation.

Weinstock condemned San Diego’s establishment, and concluded that “much of the intelligence, the wealth, the conservatism, the enterprise, and also the good citizenship of the community… organized the vigilante groups, participated in their criminal activities and encouraged others to do the same.” The American Federation of Labor Council of San Francisco also sent a team of investigators to San Diego and came to the same conclusions.

In addition the Labor Council concluded that the street speakers were nonviolent: “Beyond singing a few songs in the crowed jail and asking to have the vermin suppressed and the vile food improved… they made no trouble. Outside the jail not a single act of violence or even of wantonness has been committed! Not a blow has been struck; not a weapon used; not a threat of any kind made an I.W.W. or other sympathizer with the Free Speech movement. Such patience under the most infamous and galling inhumanity and injustice speaks well for the discipline maintained by the leaders of such men.”

After the reports were released the level of violence in San Diego declined, only to escalate once again. On May 4 a IWW member who was standing in front of the IWW hall was shot and killed by police. On May 15 Emma Goldman, the anarchist propagandist and free speech fighter, had to be rescued from vigilantes who yelled “Give us that anarchist; we will strip her naked; we will tear out her guts.”

Meanwhile her manager and consort, Ben Reitman, was kidnapped and tortured. He was driven out of town, urinated on, tarred, “and in the absence of feathers, sage brushed.” Then “with tar taken from a can (they) traced I.W.W. on my back and a doctor burned the letters in with a lighted cigar… then I was made to run the gauntlet of fourteen of these ruffians, who told me they were not working men, but doctors, lawyers, real estate men. They tortured me and humiliated me in the most unspeakable manner. One of them was to put a cane into my rectum.” When they finished with him he was dumped in the desert wearing only his underwear.

When Governor Johnson received Weinstock’s report he instructed the authorities in San Diego to end the violence or he would send in the state militia and arrest the vigilante leaders. The vigilante violence did stop but the right to free speech was not restored.

With the fight continuing a committee of San Diego citizens sent a representative to President Taft to urge his intervention, not to support the Wobblies, but to crush them. He was warned that 10,000 armed Wobblies were heading to San Diego intent on overthrowing the federal government. Taft ordered the matter investigated by the Justice Department, which concluded that there was insufficient evidence to indict the leaders of the IWW for conspiracy to overthrow the government.136

The battle continued throughout 1912 and 1913. Finally in the summer of 1914 the IWW was able to speak on the streets unmolested, although the law was never appealed, it was simply not enforced.

During these years the IWW conducted a dozen or more other free speech fights. Most of these were won by the IWW. By 1915, the IWW official position was that free speech fights should be avoided if possible as a distraction from the work of organizing the workers and leading strikes.

Everett Mill Strike Sparks Another Fight

Late in 1916 the IWW was supporting sawmill and logging camp workers in Virginia who were demanding an increase in pay, shorter working hours, and better living conditions. A strike was called for the day after Christmas. The following day the City Council passed an ordinance prohibiting the distribution of strike literature, followed by an order from the police and fire commissioners ordering all IWW members out of Virginia.

News of the strike traveled quickly by telegraph and telephone to the workers in the sawmills and lumber camps of northern Minnesota, who also voted to strike. The International Shingle Weavers’ Union of America, an affiliate of both the AF of L. and the IWW, voted to strike across the nation on May 1, 1916.

Many mills owners agreed to the demands for higher wages and better living conditions but Everett, Washington mill owners refused. By July the strike was three months old and the shingle weavers were hanging on. Most of the original 400 strikers were in jail, arrested for picketing or disorderly conduct, but about 60 were still walking the line, fighting scabs and the gunmen hired by the employers. This was actually an AF of L strike as it was not unusual for union men to carry two membership cards. The IWW first became involved in late July when IWW organizers arrived in the city.

photo from Everett Public Library

James Rowan, one of the IWW organizers tried to speak on the street on the night that he arrived and was arrested, starting a familiar pattern. It was a fight that the leadership of the IWW was reluctant to take on, as by this time free speech fights were no longer the focus of IWW direct action. So there were no mass arrests and after Rowan was released without serving jail time he went back to the streets and was rearrested. This time he got 30 days.

IWW leadership refused the request for mass arrests preferring to focus on the strike. The strikers’ situation had become desperate. Only 18 picketers remained and on August 19, 1916, a fight broke out between them and the scabs and gunmen hired by the mill owners to escort the scabs to and from work. The 18 men were taken away and beaten severely. One man was shot in the leg.

Following this incident IWW leadership sent James Thompson, the first man to be arrested on November 2, 1909 in Spokane, to Everett to speak. On the night of August 22, 1916, Thompson was arrested for street speaking, followed by Rowan and three women. Frustrated, the police decided to arrest everyone in the crowd. The next day all the arrested men and women were deported to Seattle on a steamship. The police took sufficient money from one of the Wobblies, James Orr, to pay for the passage.

The IWW was still not ready to jump into another free speech fight, although it recognized, along with the AF of L. that the strike by the shingle weavers was a crucial battle. Meanwhile, William Blackman, a federal labor mediator had arrived in Everett to assist in the effort to settle the strike. The city, mill owners, and strikers were under federal scrutiny and everyone was being careful. Meanwhile, the power to deal with the strikers and the Wobblies had been quietly turned over to the Sheriff who proceeded to organize a band of several hundred deputies instructed to drive the Wobblies out of the city by any means.

On September 11, 1916, a group of Wobblies, including Mrs. Frenette, who had been previously arrested for street speaking, tried to slip into Everett onboard the launch the Wanderer, but were boarded by the deputies, severely beaten and arrested. After a week in jail without a hearing the arrested men and Mrs. Frenette were released.

Many of the citizens of Everett were shocked by the events of September 11 and publicly said so. A mass meeting was called attended by 10,000 people, a third of the city’s population. Still, the deputies continued their harassment of the IWW. An estimated 300 – 400 were arrested and deported in October. On October 30, forty-one Wobblies were removed from the vessel Verona, driven out of town, beaten, made to run the gauntlet and abandoned in the woods.

Many citizens witnessed the beatings on board the ship before the men were removed, so the outcry against the deputies was immediate and well documented. A committee was formed to look into the allegations and reported that: “The tale of the struggle is plainly written. The roadway was strained with blood… there can be no excuse for, nor extenuation of such an inhumane method of punishment.”

While this outrage was played down by local papers, citizens disagreed with the editorials. In Seattle IWW organizers were signing up recruits for the battle in Everett. The sheriff was also increasing his supply of men, signing up new deputies until he had over 500. On November 5, 1916, Sunday morning at 11am about 250 Wobblies boarded the Verona to travel to Everett for a planned 2pm mass meeting. Pinkerton spies warned the police of the departure.

Armed deputies were sent to the dock to await the arrival of the Verona. As the 200 or more Wobblies crowded the deck waiting for the arrival of the ship at the dock, a shot ran out from an unknown person, followed by a volley of gunfire from the deputies. The deputies were placed on the dock and in the warehouses in such a manner that some at the back had no clear line of sight of the Verona, resulting in their shots hitting the backs of their fellow deputies.

Five Wobblies died, six more were missing, most likely drowned, and twenty-seven were wounded. The surviving Wobblies were ordered to the dock and searched. No weapons were found. Seventy-four were arrested for conspiracy to kill the two deputies who had been shot in the back by their own men.

Only two of the seventy-four men would be tried. The first was Thomas H. Tracy. His trial was set for March 5, 1917, and received national press. It proved to be one of the longest and most important trials in American labor history. It was not just the defendant, but the IWW, the officials of Everett, and the right of free speech that were on trial. Fred Moore of Spokane and George Vanderveer were the counsel for the defense. On May 4, 1917, a verdict of not guilty was returned by the jury. A second defendant was later tried which also resulted in a not guilty verdict. Charges against the other seventy-two defendants were dismissed.

The trial proved that the opponents of the IWW were acting outside the law. Shortly after the trial, the mill owners yielded to the demands of the strikers, granting the right of the union to organize, and raising wages. A sweeter victory would have been indictments against the sheriff and his deputies who murdered the IWW men on the Verona but that was wishing for too much.

By the eve of the war most of the IWW membership was west of the Mississippi. The IWW had become a western union, with a wide range of influence from the harvesting fields to the lumber camps and construction sites, to the mines and oil fields. The focus had shifted from free speech fights to the encouragement of the membership to get and keep jobs, organize and be prepared to strike if necessary for better wages and working conditions. Sabotage was also played down. The IWW had lost its radical edge, just in time to be brutally assaulted on all fronts by the federal government’s wartime crackdown during the fall of 1917.

Lessons Learned

When vigilante groups became part of the official response, sanctioned and authorized to get rid of the Wobblies, then the level of violence escalated to include murder and more brutal methods of torture. The violence was also not simply directed at the Wobblies or the free speech participants, but spilled over onto the liberal or moderate community.

A case in point is that the San Diego Herald was certainly not a radical paper, but its editor was still kidnapped and its operations forcibly shut down. No one was arrested because the vigilantes operated outside of the law. The conservative newspapers implied that the editor, Sauer, got what he deserved: “Sauer has printed articles urging violation of law and bitterly and vindictively denouncing the authorities of this city. Consequently he should not complain if he is made a victim of the very thing he has been advocating.”

Moderates were harassed until they felt compelled to be silent. Meanwhile the editor of the San Diego Evening Tribune could advocate murder without any repercussions from the authorities: “For weeks the city has been infested by a gang of irresponsible tramps, thieves, outcasts and anarchistic agitator, calling themselves Industrial Workers of the World…. They have not yet resorted to violence…. Why are the taxpayers… compelled to endure this imposition? …the law which these lawbreakers flout prevents the citizens of San Diego from taking the impudent outlaws away from the police and hanging them or shooting them. This method of dealing with the evil… would end the trouble in half an hour.”

Eventually the persecution and repression made it difficult to recruit men to join in a free speech campaign. By the time World War I started in Europe, the free speech movement was mostly just a memory. Wartime hysteria and the characterization of the Wobblies as a “red menace” ensure the eventual decline of the IWW’s ability to mobilize and organize workers.

During the fall of 1917, every IWW local office in the nation was raided by the federal police, and indictments were brought against some 2,000 IWW leaders. By the end of the decade many were in prison and others had fled to Russia. Although the IWW still exists today, the 1917 raids effectively eliminated the IWW as a force in labor.

The effort of the IWW to unionize the migratory and unskilled factory workers was in many aspects heroic. This historical lesson should be remembered, as should the response of the moneyed and privilege class.

What drew these men from all parts of the country to travel hundreds of miles on an open boxcar only to get arrested, jailed, beaten and sometimes tortured or killed? Many of the free speech movements occurred during the winter, such as the one in Spokane when travel in boxcars, or even on top of boxcars, would subject the Wobbly to conditions of extreme cold. These were trips of hardship made by men who had very little money and could hardly afford to eat while on the journey.

These were not job migrations; there was no award at the end of the trip. These were rough men, mostly uneducated, often in this country for only a few months or years. Many were also illiterate, especially in the English language. Many had no sense of the Bill of Rights, could not recite it, and believed it protected only the rich and the moneyed, but not them.

These men came for other reasons, fighting for the right to live without the fear of hunger and want, the dream of a family, a wife and children, and the knowledge that this could only happen when they had a steady well-paying job or a piece of land to call their own. Perhaps these men came to the free speech cities out of a need to feel a sense of belonging or a sense of purpose. Perhaps it was for the adventure. Perhaps the men came and allowed themselves to be beaten and jailed because they had an abiding belief in the American dream.

Read part 1 of this series “The Spokane Free Speech Fight” at wafreepress.org/article/090903history.shtml.

Dale Raugust is a Spokane historian and a retired lawyer who is in the process of writing a book on the early history of Spokane. The above article is a condensed excerpt of his thoroughly footnoted draft.