|

Cartoons of

Dan McConnell

featuring

Tiny the Worm

Cartoons of

David Logan

The People's Comic

Cartoons of

John Jonik

Inking Truth to Power

|

Support the WA Free Press. Community journalism needs your readership and support. Please subscribe and/or donate.

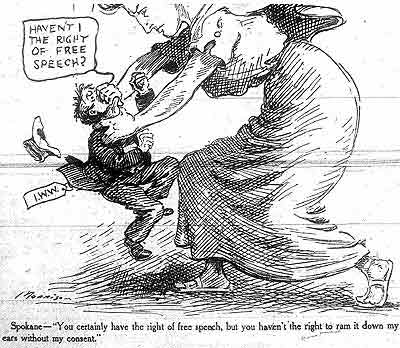

an anti-IWW editorial cartoon from the Spokane Spokesman Review, circa 1909.

FANNING THE FLAMES OF DISCONTENT

Part 1: the Spokane Free Speech Fight

Read part 2 at wafreepress.org/article/091109history-raugust.shtml.

By Dale Raugust

Did you know Spokane was

likely the site of the first hunger strike in the US? It happened during

a time when the IWW was waging—and winning—many “free speech

fights.” One of the most bitterly fought of these was in Spokane.

Here’s the story.

During the winter of 1909-10, Spokane Washington was the battleground of one of the most significant free speech fights in the history of the United States. Men and women stood in defiance of a law which prohibited public speaking on the downtown streets of Spokane. This was the gathering place for migratory workers who assembled along Stevens Street every morning except Sunday, and were charged a dollar or two by corrupt employment agencies which sent them off to non-existent jobs or jobs which lasted only a few days.

After a few days on the job, workers were often fired, to be replaced by other men sent by the employment agencies. This created what union organizer and agitator Elizabeth Gurley Flynn called “perpetual motion—one man going to a job, one man on the job, and one man leaving the job.”

William Haywood of the Western Federation of Miners testified before a Senate Committee in 1916 that the IWW had documented thousands of cases, including Deeks and Deeks, a mining firm near Weatherby, Oregon which hired and fired 5,000 men during the summer of 1908 to fill a crew of 100 men. At other times an employment agency would send a hundred men to fill 10 vacancies or dozens of men to a job site that did not request any workers.

Not only did the men have to pay the fee to get the job but they had to spend the money and time to travel to nonexistent jobs as far away as the mines of Montana.

The newly organized Industrial Workers of the World came to Spokane during the summer of 1908 to stop this abuse of working men and organize a local chapter of the IWW. This is the story of that effort and the men and women who led the fight for free speech and unionized labor in Spokane, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, one of the best speakers on the IWW circuit.

Prelude to the Fight

The Industrial Workers of the World conducted approximately 26 free speech fights in western cities between 1908 and 1916. During 1908 and 1909 several short free speech fights were fought in the northwest.

In Portland the law prohibiting free speech was declared unconstitutional and the city responded to the employment shark allegations by opening up a free employment agency to help people get jobs, thus decreasing the profits of the employment agencies and reducing the conflict in the city.

The Seattle and Missoula battles against the employment agencies were also short lived with good results for workers. In Missoula the charges against the speakers were dismissed and the IWW was allowed to organize the workers.

The issues in Spokane were the same as in Missoula, “shark” employment agencies charging fees to send men to nonexistent jobs. The men were then stranded in remote places without money or friends. The city of Spokane would prove to be, however, more resistant to the efforts of the IWW.

Spokane was significant in the free speech and labor fights because in 1909, the city had a population of over 104,000 in the 1910 census and was considered the central metropolis for all of the inland Pacific Northwest. In the winter the harvest and railroad construction workers, miners and lumbermen came to Spokane to rest up and spend what little money they made on skid-row hotels, whiskey and women.

Spokane was also the central location for unemployed workers to gather and be dispersed to new jobs by employment agencies. A long time Wobbly, Richard Brazier, described Spokane in 1907 as “one of the few wide-open towns, so common in the Northwest.” What you wanted you could get, “vice was rampant, prostitution and gambling were legalized.”

James H. Walsh, a union organizer with the IWW arrived in Spokane during the summer of 1908. Walsh had just left Nome, Alaska, where he organized a local branch of the IWW and started a newspaper called the Nome Industrial Worker, the predecessor of the Spokane Industrial Worker. Spokane was considered the greatest challenge to the IWW. Not only was it a large city, but it was also the employment hub for eastern Washington, eastern Oregon, northern Idaho and western Montana. At that time there was no prohibition against street speaking.

During the summer and fall of 1908, James Walsh was so successful in signing up new members, 1,500 by October, 1908, that the employment agencies formed an association and took their complaint to the City Council, which passed in October, 1908 an ordinance prohibiting “the holding of public meetings on any of the streets, sidewalks, or alleys within the fire limits.” The purpose of the ordinance was purportedly to control traffic so that fire wagons would not be delayed. The ordinance was to be effective on January 1, 1909.

The IWW was allowed to meet in public parks or vacant lots but was prohibited from speaking in front of the employment agencies which were all located within the central business district on Stevens street. After their first union hall was burned down Walsh and the IWW rented a hall at the corner of Stevens and Front Street, 412-420 Front Street, (now Spokane Falls Blvd.) where they published their newspaper, The Industrial Worker, and where they could hold indoor meetings.

At first there were no disturbances. IWW organizers did speak on streets in defiance of the ordinance, sometimes resulting in arrests.

In early January, 1909, Walsh spoke on the streets to prevent a large crowd of angry workers from rioting and destroying the office of the Red Cross Employment Agency, one of the worst offenders.

As reported by the Spokesman Review, an angry crowd of 2,000 to 3,000 workers had gathered outside of the Red Cross Employment Agency ready to riot and destroy the offices “when James H. Walsh, organizer of the Industrial Workers of the World, mounting a chair in the street, stemmed the rising tide of riot and pacified the multitude. In the opinion of the police had it not been for the intervention of Walsh a riot would surely have followed. Walsh discouraged violence and summoned all workers to the IWW hall where he warned the crowd against any outbreaks.”

Walsh was eventually arrested

in late March,1909. The Industrial Worker reported in the April 8, 1909

issue that “Judge Kennan tried J. H. Walsh in the Superior Court on

Tuesday, April 6, and made short work of it.” The Industrial Worker

reported that the jury was out for six minutes and “might have taken

longer to ‘arrive’ at a verdict but it seems the cow belonging to

the jury foreman was sick and the juror had to go home.”24

The Battle Begins

Flynn did not stay in Spokane until mid-November, 1909, after the free speech movement had started and hundreds had been arrested. Flynn had been following IWW campaigns in other cities that summer, but had made trips to Spokane during the summer of 1909 to raise awareness and funds for the IWW. She spoke in Spokane on June 29, 1909, declaring that:

“The working class of this country have not learned that they must organize an international union, a union that lays aside secondary considerations of creed; the language that they worship their God in; the nation and place that they are born in; and the color of their skin and the texture of their hair and all of these minor features, and remember the fact that first and last and all the time they are wage slaves lined up against a solid capitalistic force.”

The Spokane City Council responded to the Flynn attack on capitalism and the “slave labor system” by amended the prohibition against street speaking on August 10, 1909, to exempt religious groups like the Salvation Army and the Volunteers of America from the ordinance. The response from the local IWW chapter was to openly challenge the law.

On October 25, 1909, James Thompson, local organizer for the IWW, had been arrested and charged with violating the ordinance. At his trial the new amended law which exempted religious groups was declared unconstitutional but Municipal Judge Mann, who then declared “that the old ordinance, 4881, was now in force, which provides for the arrest, of persons obstructing the streets or otherwise committing nuisances or infringing upon the rights of others.”

Thompson was convicted under the original law. The IWW then announced their intention to challenge the original law. They called out to all IWW locals to come to Spokane to join the fight which was scheduled for November 2, 1909. Elizabeth Flynn wrote for the Industrial Worker that “only going to jail by the hundreds will” accomplish their objectives.

On the morning of November 2, 1909, the Spokesman-Review announced that Police Chief Sullivan had called in every available officer to deal with the expected disturbances. Chief Sullivan said: “We have plenty of room and can accommodate 500 or more if necessary.”

County Commissioner F. K. McBroom announced that the county has established a special rock pile on the property owned by “Colonel D. P. Jenkins at Monroe street and Broadway…” That evening the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported that “between 3 and 4:30 this afternoon….well over a hundred” men were arrested.

The paper reported that the IWW intended to put 500 more on the soapbox tomorrow and that

“Orders have gone in to the fire department that if the IWW continue what they term their ‘matinees’ tomorrow to assemble and with well directed streams from the big hose scatter the crowd…. The law breakers are packed into jail 20 and 25 to a cell. Several women have met the same fate and others are expected to follow their feminine companions in the street speaking.”

In addition to the speakers, union leaders were arrested in the union hall at Stevens and Front and charged with criminal conspiracy, the encouragement of others to break the law.

The next day the call went out by telegraph for additional men. The Portland IWW announced they would send 500 men with 200 already on the way. In the next issue of the Industrial Worker, November 10, 1909, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn wrote:

“This fight is serious. It must be won. Remember, ‘an injury to one is an injury to all’. We must never give up. We have just begun to fight. The men in jail have refused to work on the rock pile. They are starving rather than eat the dry bread flung at them. These men are brave loyal supporters of the cause. They are heroes in the battle for labor. “Can you afford to be a coward?’ (emphasis in original) Sympathy won’t win this fight. Only going to jail by the hundreds will do that.”

The Spokane Socialist Party and the Women’s Club, a suffrage group, announced their support for the IWW. A mass meeting was scheduled for the evening of November 3, 1909 at the Masonic Temple “with addresses by Mrs. ZW Commerford of the College Women’s Equal Suffrage Club, Mrs. Rose B. Moore, (wife of IWW attorney Fred Moore), chairman of the social economics department of the Women’s Club, and by a clergyman whose name was not given.”

The Spokane Press announced its support for the street speakers by publishing the IWW advertisements of meetings and reporting on the conditions of the men and women in the county jail. The newspaper reported that a recall petition had been started against Mayor Pratt for cooperating with the Industrial Workers of the World and that “Eugene V. Debs, the great socialist leader of the nation in politics, has started west,” to speak in Spokane.

The Spokane Press referred to the men and women arrested as “volunteer martyrs” and that another two hundred men plan to be arrested the following day. The following day under the headline “Human Bedlam in the City Bastille” The Spokane Press reported on the deplorable conditions of the jail declaring that: “One of the men, James D. Gordon, who claims to have been kept for more than 30 hours in a veritable sweatbox with 33 other prisoners is said to be in a serious condition…”

In an editorial The Spokane Press declared that the IWW has represented itself well, “all rowdyism (sic) has been strictly prohibited… In the same manner the police must carry out their program. Every brutal arrest, every unfair use of power, will only react (sic) on the city government, and thus forward the cause they are instructed to suppress.”

On November 3, 1909, The Spokesman Review reported that 103 men were arrested and that the prisoners stayed up all night giving speeches “in six different languages” followed by the songs of the IWW.

The police shut down the press of the IWW’s Industrial Worker.

That evening the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported that any man convicted of disorderly conduct in an attempt to speak on the streets would be given a sentence of 30 days on the rock pile and that any man who refused to work would be put on bread and water and kept in a dark cell.

To counter the quickness of justice and cause more hardship on the city, the IWW announced that each man arrested would demand a separate jury trial. On the second day 97 more men were arrested. All the men and women arrested from both days were charged with disorderly conduct instead of violating the street speaking ordinance. Chief of Police Sullivan, in consultation with Judge Mann, determined this charge would be more difficult to attack in court.

On November 4, 1909, the Spokesman-Review reported that two of the three women arrested the previous two days had been released. 33 of the men were sentenced to 30 days on the rock pile. Additional arrests were made of men who were not speaking but who were instead union organizers or editors of the Industrial Worker. Also arrested were men reading or speaking to the crowd from their office window overlooking the street. Attorney Steven Crane was arrested and charged with inciting a riot as he spoke from his office window.

“Justice Mann, irritated by the flat contradiction of officers’ testimony uttered by prisoners charged with disorderly, told the men that if the practice of denying all charges was kept up, there would be some arrests for perjury.”

The right of jury trial was effectively quashed by the court’s announcement that jury trials would be held only one hour a week, thus requiring weeks in jail awaiting the opportunity for a jury. Later that evening the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported that the men arrested refused to work in the rock pile and instead were content to survive on a diet of bread and water.

That night, The Spokane Press announced that an “indignation meeting” would be held in the evening to protest the free speech arrests. No arrests were made on the third day of the demonstrations, the police apparently deciding on new tactics.

The Chronicle reported that: “A detail of officers was sent to the place and succeeded in dispersing the crowd, after a few minutes. It was necessary for the officers to use a little violence in many cases to make the men move on.”

It was not only the Spokane papers that covered the arrests. The Portland Oregonian gave the story complete coverage and within a week the story had gone national. On November 4, 1909 the Oregonian reported that “1,000 men were on their way to Spokane in empty freight cars to join their IWW brothers. By November 5, the city jail was filled to overflowing, ‘Still they come, and still they try to speak.’” The men arrested were subject to brutality and torture by “sweating” them in crowded cells, then transferring them—drenched—into cold cells.

Other men were arrested not for street speaking but for showing support to the street speakers. F. Bordine, “a well known Swedish music teacher” was arrested for “unlawful assembly” when he applauded one of the street speakers.

William Z. Foster, a correspondent for the Seattle based labor paper, The Workingman’s Paper, was arrested for just being in the crowd at a free speech event. He spent 47 days in the Spokane City Jail and published his report on January 22, 1910. After his arrest he was interrogated for half an hour and then placed in the sweatbox.

Five witnesses testified at his trial that he was a correspondent and was not speaking, yet he was found guilty and sentenced to 30 days plus a $100.00 fine. He was immediately placed on a bread and water diet. He received, like all the prisoners “one-fifth of a five-cent loaf of bread twice daily”. Despite his refusal to work he was shackled by the leg to another man and by the other leg to a fifteen pound ball and lead to the rock pile. The weather was very cold and many of the men worked just to stay warm.

Back at the jail Foster reported how the men, even in jail, held “rousing meetings” electing officers and set aside specific time for strategy sessions. Prisoners arrested for the crime of being poor (vagrancy) and other minor crimes were signed up. Procedures were put into place to deal with complaints of police brutality.

Jail authorities, decided the men were getting too organized so they remove those prisoners perceived to be the leaders and placed them in the “strong box” (solitary confinement), normally reserved for hardened criminals. There was no medical treatment. Foster describes a man who died from what was apparently a seizure.

Foster, suffered from an

ulcerated tooth which prevented him from sleeping as the pain was so

intense. For ten days he suffered until he was released on a day bond

to go to the dentist.

Photo from the Spokane Spokesman Review newspaper. The paper had a generally hostile editorial stance toward the free speech fight, though a number of other newspapers and civic organizations were supportive of the Wobblies’ efforts.

Torture of the Prisoners

When the jail overflowed an abandoned unheated school house, Franklin School, was used for the prisoners. Conditions at Franklin were even worse than at the city jail. The building had no heat and Spokane was going though a cold spell. The men slept in below freezing temperatures at night. To make matters worse, at the slightest provocation the police would turn the icy water from a fire hose on them and then make them stay in their cold wet clothing.

“Three times a week the police shuttled the prisoners from the school, eight at a time, to the city jails for baths. Guards stripped the prisoners, pushed them under a scalding spray followed by an icy rinse, and brought them back to their freezing quarters in the school. Three Wobblies died in the completely unheated Franklin School. One month, 334 prisoners were hospitalized, another month 681.”

The Wobblies on the street rallied to the support of the prisoners being transported, throwing fruit, bread and tobacco at them. Those who managed to catch a piece of fruit were beaten by the police until they dropped what they had caught. One man had an apple in his month and a police officer broke his jaw to force him to release it.

Another man, Joseph Gordon, in a letter to the editor of The Workingman’s Paper, a Seattle based labor newspaper, described his own experiences in the Spokane jails. Gordon said he was one of the first to be arrested on November 2, 1909. He was “thrown into the Spokane sweatbox, well-named ‘The Black Hole of Calcutta,’ along with… about 28 others….” Gordon said that the jailor “closed the air-tight steel door” on the prisoners and turned on the heat. There were 28 men in the cell crammed so tight that “we could not sit down. We were so crowed that we could not conform to the ordinary decencies of human beings, and were compelled to stand in our own offal.”

The prisoners spent 29 hours in the cell without food or water and were then moved to an unheated cold cell for four hours until it was time for them to appear in court before Judge Mann. Many of the men fainted in court including Gordon who consequently could not enter a plea. When he woke up he had been discharged.

To protest the rations of bread and water many of the men went on a hunger strike which lasted for about ten days. The Spokane Press reported the start of the strike:

“The stomach pump will be in demand at the city jail. Like the women suffragists of England who refused to eat the meager prison fare offered by the authorities, and starved till, alarmed at their condition, the police attempted to force food into their stomachs with the pump, 200 members of the Industrial Workers of the World, under sentence in the city jail, on bread and water, have begun a hunger strike... Thus Spokane claims the distinction of having seen the first hunger strike in the United States.”69

Two days later The Spokane Press reported under the headline “Hunger Strikers Sick But Still Fight” that the hunger strike was continuing and that the men in prison were in high spirits. In the same issue the newspaper reported on the treatment received by attorney Samuel Crane. Crane had not spoken on the street but from the window of his law office. He declared that he was beaten and punched and kicked before arriving at the jail and once at the jail was immediately placed in the sweatbox.

He described his entrance into the cell: “On entering the cell a hot fetid gust as of a fiery furnace struck me. The bottom of the cell was wet and soggy; the odor insufferable, like the stench of a cesspool.”

The women in jail did not receive the physical torture of hot and cold water and beatings that the men received; but theirs was another kind of terror. Agnes Thelca Fair was arrested on November 5, 1909. She was first confined with another woman, who Agnes Fair described as a “fallen woman.” Then the police removed the other woman and put Fair in a dark cell by herself.

Later “about ten, big burley brutes came in and began to question me about our union. I was so scared I could not talk. One said, ‘We’ll make her talk.’ Another said, ‘She’ll talk before we get through with her.’ Another said, ‘F**k her and she’ll talk.’ Just then one started to unbutton my waist, and I went into spasms…”

Fair passed out and when she awoke she was in bed. Next to her was a “man disguised as a woman… I thought it was a drunken woman until the officers went out. Then I felt a large hand creeping over me…” Fair screamed “frantically” and was “frothing at the mouth.” She was relieved when two other female IWW prisoners were brought to her cell.

As the men in jail fought to stay alive, the men on the streets continued to fight to get arrested. The city of Spokane decided on some new strategies. About half of the men arrested were not US citizens; so the solution seemed to be to deport those foreigners arrested. This would take the cooperation of the federal government and time for processing. On November 7, 1909, the Spokesman-Review published a story that the city was now working in cooperation with the federal government to deny citizenship to those foreigners who were participants in the free speech fight.

The city also pressured landlords not to rent to the IWW, thus forcing them into open air meetings. Inside the jail the leaders were separated from the other prisoners and then the rank and file members were told that the leaders are enjoying steak and potatoes while they survive on bread and water.

A picture of the leaders with plates of food set in front of them was taken by the Spokesman- Review and published in an attempt to drive a wedge between the leaders and the membership. The tactic did not work as the leaders went on a hunger strike in solidarity with the workers.

The tactic of the hunger strike, meant to evoke sympathy for the cause in the conscience of the oppressor, was called off after city officials declared that the men in jail should be allowed to kill themselves by hunger, that this mass suicide would be good for the city as it would rid the city of the rabble.

By November 10, 1909, both the city and county jails were full as was the Franklin school. New prisoners were now taken to the federal prison at Fort George Wright. Within a day, 100 prisoners had been confined at the fort.

The public’s opinion of the Wobblies was a reflection of the attitude of the city of Spokane. In editorial after editorial the Spokesman Review described the Wobblies as less than human. The Wobblies were described as men with no work ethic “who have learned to despise all human authority, (and) have become worse than worthless units of society…”

A Salvation Army worker attempted to conduct services at the jail and reported that: “In all my experiences with prisoners, I have never seen such a hard-looking lot of men as those now in jail for street-speaking…. I am at a loss to find a name which would apply to them. They are not men.”

The suffering and dedication of the street speakers generated national publicity and seemed to obtain results. On November 15, 1909, the Spokane Dailey Chronicle reported that Charles F. Hubbard, state labor commissioner, was starting an investigation on the employment sharks and that the problem was not confined to Spokane but existed in every major city in the state.

It was announced by the

labor commissioner that the investigation would begin in Bellingham,

which did not immediately help the situation in Spokane.83 Into this

tense situation arrived the “girl agitator”, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

The Arrival of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

When Flynn arrived in Spokane she reported to the IWW hall and surprised the men in charge with her obvious pregnancy. It was decided that it was too dangerous for her to speak on the streets and risk arrest so she was assigned to indoor speaking events and fund raising activities.

When the editors of the Industrial Workers were arrested once again, Flynn took over as the new editor. On November 30, 1909, as she was walking to the IWW hall she was arrested and charged with criminal conspiracy, a state charge carrying a maximum penalty of five years in prison. Flynn described her arrest in an article from The Workingman’s Paper and in her autobiography: “I was taken to the chief’s office where Prosecutor Attorney Pugh put me through the ‘third degree.’” Flynn’s attorney, Fred Moore came to the door “and asked for admittance but was denied.” Flynn refused to answer the questions. She said that the police were “all extremely courteous, probably due to the information conveyed to them over the phone that my physical condition was such that it would be dangerous to be otherwise. But the ordeal of a rapid fire of questioning is not as easy as it looks from the outside.”

Flynn goes on to describe

the night she spent in the city:

“I was placed in a cell with two other women, poor miserable specimens of the victims of society. One woman is being held on a charge that her husband put her in a disorderly house. The other is serving 90 days for robbing a man in a disorderly resort in Spokane. Never before had I come in contact with women of that type, and they were interesting. Also, I was glad to be with them, for in a jail one is always safer with others than alone. One of the worst features of being locked up is the terrible feeling of insecurity, of being at the mercy of men you do not trust for a moment, day or night. These miserable outcasts of society did everything in their power to make me comfortable. One gave me the spread and pillow cover from her own bed when she saw my disgust at the dirty gray blankets…the girls gave me fruit that had been sent to them. They moderated their language…. in the morning they gave me soap and clean towels…”

Next Flynn made allegations that the two women in the cell with her were prostituted during the night. These allegations sent shock waves though the community and prompted the police to raid the IWW office and take every issue of the Industrial Worker that the article was to appear in. They then shut down the presses damaging the equipment so that no further issues could be printed.

Despite this action the

story went national, first published in the December 11, 1909 issue

of The Workingman’s Paper, and reprinted in many other newspapers

across the country. This is how Flynn described what happened overnight

in the city jail:

“The jailers are

on terms of disgusting familiarity with these women, probably because

the later cannot help themselves or don’t care… They are unconscious

of their degradation and solicit no sympathy. Perhaps they shouldn’t

be conscious, for society is to blame and not they. I was put in with

them about 11 o’clock, yet the lights were burning bright… so I

threw my clock over me and tried to sleep… The younger girl remained

up… Finally the jailer came, opened the cell door and took her out.

She remained a long time and when she returned I gathered from the whispered

conversation with the older one, the following: that she had been taken

down to see a man on the floor below… she went again and remained

a long time… Taking a woman prisoner out of her cell at the dead hours

of night several times to visit sweethearts (the term that the woman

used to describe the men) looked to me as if she were practicing her

profession inside the jail as well as out.”

The police seized the paper under the criminal libel law, a law commonly used to suppress the freedom of the press, and which no longer exists on the books in Washington State. The Spokane Free Speech Fight was a fight for more than just free speech, but also freedom of the press and the right to peaceably assemble.

The day before this article appeared Flynn was convicted in Municipal Court of criminal conspiracy, but immediately appealed to Superior Court. Meanwhile the free speech fight in Spokane had hit a snag caused by the switchmen’s strike against the railroads. With the rails shut down there was no way for the migratory workers to get to their jobs, or to get to Spokane to participate in the free speech fight.

Meanwhile, without the railroads to bring in new recruits, the IWW shifted tactics, filing dozens of damage lawsuits against the city, and city officials totaling about $120,000. These lawsuits were filed by IWW members who had been beaten or otherwise mistreated while in the custody of the city. Personally named were all the city officials and selected police officers who were identified as being the worse of the lot.

The Spokane Press editorialized on November 9th that Spokane should adopt the same street speaking law that the IWW won in their fight in Seattle, an ordinance which prohibited street speaking only during the hours of 5 to 7 pm, as the purported purpose of the law was to regulate traffic and keep the fire lanes open during rush hour.

The Industrial Workers were willing to accept such a law and a week later, on November 22, 1909, began circulating a petition to put an amendment to the anti-street speaking ordinance on the ballot for the registered voters of the city of Spokane to vote on. Twenty percent of the voters could have put the matter on the ballot.

Even with no additional arrests for street speaking, arrests continued for IWW workers. On December 1, 8 boys, ages 11 to 16 were arrested in the IWW hall as they were getting ready to deliver the latest issue of the Industrial Worker newspaper. The boys were all transported to the juvenile court. The Spokesman-Review reported that delinquency charges would be filed against their parents for allowing the boys to be employed by the IWW.

Chief Sullivan said that: “If we stood by and did nothing these boys would (learn) revolutionary principles which would influence them throughout life.”

In responding to the arrests Gurley Flynn wrote “Is the time coming in this United States when Socialists are to be deprived of their children because they are Socialists? There is no insult too gross, no trick too low, no act too heartless for these brutal representatives of law and order to resort to. Who is to fix the standard of what constitutes proper care for children and correct ideas to teach them—shyster lawyers, drunken judges and ignorant, illiterate police officers?”

On December 20, 1909 the IWW hall was again raided in an effort by the police to shut down all IWW operations in the city. This time the police drove about 200 IWW men into the streets where they assembled next to the rock pile where IWW prisoners were breaking rock. An outdoor speech was given and more arrests were made.

Earlier in the day five men had been arrested for vagrancy when they attempted to sell the Industrial Worker on the street. The vagrancy law was normally reserved for men who appeared to be out of work and who were hanging about in the downtown area, but now that crime had been extended to cover a man who was working, although at a job that the police did not agree with. Nine additional arrests were made on December 22, 1909.

After the end of 1909, the arrests stopped for a time. Flynn was out of town speaking at mining camps and cities across the Northwest. By now she was five months pregnant and out on $5,000 bond posted by several womens clubs in the city. The Municipal Court verdict had been appealed to the Superior Court and her retrial was scheduled for early February, 1910.

During this time there

was only an occasional mention of the IWW in the Spokane papers. The

Industrial Worker was now being published in Seattle where it could

do so without weekly police raids. Everyone was catching their breaths

for what was announced as the second phrase of the Free Speech Fight

set to begin in early March. In the interim, Flynn’s lawyers were

preparing for their new trial.

The Trial of Flynn

Flynn was first tried in Justice Mann’s Municipal Court in early December, 1909, and was convicted of conspiracy to violate the anti-street-speaking ordinance. Her attorneys immediately appealed the conviction to the Superior Court where she would receive a trial before a jury of twelve men. The trial was set to begin in early February, 1910.

Often the newspapers presented the testimony in an amusing manner. On February 17, 1910, the Spokesman Review reported that Hartwell Shippery of Chicago was called as a witness. Shippery was at that time confined in the Spokane City Jail where he was serving six months on a conspiracy charge. He was not one of the men originally tried with Flynn but was tried separately and did not appeal.

Shippery admitted he was the author of the article that appeared in the Industrial Worker entitled “The Story of the Spokane Fight”. He admitted “having written the line ‘the illiterate and parasite lackey of the capitalistic class, Judge Mann,’ and ‘that long, lean, lank, fish-eyed monster, Chief of Police Sullivan’” which brought the audience and Elizabeth Flynn to laughter.

After Shippery was dismissed from the witness stand he was, according to the Spokesman Review, surrounded by many women “and feminine hands pressed their encouragement and pretty lips whispered congratulations to him while the deputy sheriff waited, disgustedly, to escort him back to the remained of his six months’ service for Spokane County.”

Other witnesses were called by the defense to testify about the conditions of the prisoners, technically not relevant to the issue of guilt or innocence, but information that the defendants wanted to make public.

The star witness, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, took the stand on February 17, 1910, and answered each question with a speech denouncing the capitalistic system, the employment agencies, and city and jail officials. “The most bitter partisan could not but admit her sincerity and frankness as she gave her testimony, although there may not be the smallest agreement in the detail of her statement.”99

With the testimony concluded, all that was left was closing arguments. Before the arguments were scheduled one member of the jury, a Mr. Ford, became ill with rheumatism, which delayed the closing arguments for several days. It was during this time that Prosecutor Pugh gave an interview to the local newspapers that caused a bitterly contested motion to dismiss the charges or grant the defendants a new trial in a different venue.

This interview was claimed by the defendants’ counsel to be a deliberate attempt to influence the jury. The jury men were not sequestered but allowed to go home after each day in court so it is likely that they read the coverage in their newspapers and in conversations with friends and members of their family, although the judge instructed not to do so.

Pugh told a Spokesman Review reporter that he feared for the jury’s safety should they return a verdict of “not guilty.”

On Saturday, February 20, 1910, his interview was published. Pugh said that “it is well known that a great uprising is now being planned by the Industrial Workers of the World for Spokane in March and the scenes that have been laid in Spokane in the fight over will be insignificant in comparison with the viciousness of what may be expected in March. I cannot think of such a state without blood being spilled, and as sure as there is bloodshed, someone is going to get hung.”

The next Monday, as court resumed, motions were filed to dismiss the charges and declare a mistrial and once again for a change in venue. The motions were both denied.

Final jury deliberation continued for over seventeen hours until a verdict was reached. Flynn was declared not guilty, but a co-defendant, Charley Filigno was found guilty. Some thought this was because Flynn was obviously pregnant and the jury took sympathy on her. Flynn insisted on making her own closing argument and in doing so she appealed to the emotions of the men on the jury describing for them in vivid detail the working and living conditions of the transient workers as well as the incidents of police brutality and the condition of the jail.

She also acknowledged that she tried to convince men to come to Spokane to speak on the streets, and thus to violate the law in order to be arrested and fill the jail. The prosecutor was furious by the finding of not guilty. As the jury foreman, George R. Cheney, told the prosecutor: “She ain’t a criminal, Fred, an’ you know it! If you think this jury, or any jury, is goin’ to send that pretty Irish girl to jail merely for being big hearted and idealistic, to mix with all those crooks down at the pen, you’ve got another guess comin’.”

Flynn was surprised that she was acquitted. She later wrote in her autobiography that: “By this time I was obviously pregnant and even the fast-fading Western chivalry undoubtedly came into play.”

A more reasonable explanation for the acquittal was that the conspiracy alleged by the indictment was to have taken place between October 20 to November 12, 1909, and Flynn was not in Spokane during this time, arriving on November 16, 1909. There was also testimony that her image and name were used on postcards without her knowledge.

It was not unusual for Flynn’s image to be used on promotional mailings and posters. The verdict was analyzed as a compromise by the Spokesman Review, but it can fairly be concluded that the jury followed the law and rendered a verdict that complied with their instructions. The jury instructions, available within the microfilmed court file also appear to have followed the law and been fairly given.

With the trial over the IWW prepared for another demonstration to begin on March 10, 1910. Prior to the deadline the IWW organizers and the city engaged in negotiations and reached a compromise which essentially gave the IWW a complete victory.

Participants in the negotiations included for the city of Spokane: Mayor Pratt, Chief of Police Sullivan, Prosecuting Attorney Pugh, and corporate city attorney John Blair. Representing the IWW were JJ McKelvey, JJ Stark, DJ Gillispie and William Foster.

Spokane agreed to allow the IWW to hold public meetings within their hall, to release all men and women confined in jail for public speaking after the conclusion of their sentences or within 90 days whichever occurred first, to publish their newspaper, the Industrial Worker without interference subject to the normal libel laws. Mayor Pratt also agreed to use his influence to convince the city council to repeal the anti-street-speaking ordinance, and replace it with an ordinance similar to Seattle’s.

In return the IWW agreed to dismiss all damage suits against the city and officials of the city which had now totaled about $130,000 in requested damages, to follow any new street speaking ordinance passed by the city council as outlined above, and to not file any appeals of recent convictions including that of Filigno. The most significant victory for the IWW was the repeal of the licenses of 19 out of the 31 employment agencies that were the biggest abusers.

The compromise was generally well received although it required the agreement of individuals who had suffered abuse at the hand of the police and who had filed individual lawsuits. The IWW could not negotiate the dismissal of these lawsuits; only exert influence to do so. The lawsuits were mostly dismissed, however, and the IWW went on to organize the workers in Spokane.

With the investigation

of the employment agencies by the state labor secretary new laws were

passed requiring the employers to pay the fees for the procurement of

employees, thus ending the abuses. Laws which prohibited employment

agencies from charging workers a fee for finding them a job were declared

unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in 1939, although

as the depression ended and World War II began, jobs became plentiful

and it was no longer a labor issue.

Read part 2 at wafreepress.org/article/091109history-raugust.shtml.

Dale Raugust is a Spokane historian and a retired lawyer who is in the process of writing a book on the early history of Spokane. The above article is a condensed version of his thoroughly footnoted draft.