|

Cartoons of

Dan McConnell

featuring

Tiny the Worm

Cartoons of

David Logan

The People's Comic

Cartoons of

John Jonik

Inking Truth to Power

|

Support the WA Free Press. Community journalism needs your readership and support. Please subscribe and/or donate.

posted July 24, 2009

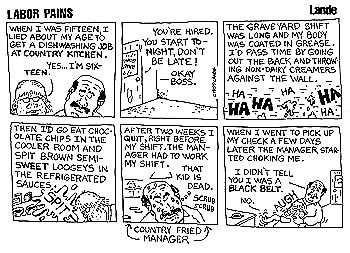

cartoon by Dick Lande

MARIA

What does a woman have to go through to get paid on the high seas?

by John Merriam

This is a true

story. Some names have been changed to reduce legal expense.

"Why do you want to go to Alaska to take a nurse’s deposition? You could settle this case for less than you’ll probably bill the underwriter for going up there.” I was speaking on the phone to the opposing lawyer. The case involved a claim for wages from a fish processing ship in the Bering Sea.

“This case won’t settle. My client doesn’t care what it costs for me to go to the Aleutian Islands. We’ll show that the nurse told the fishing company to remove Maria from the vessel for her own good because she had a sexually transmitted disease. We’re acting on principle.”

“OK, Jill, so be it. I’m not going to Alaska for this case. I’ll participate in the deposition by telephone from my office.”

My client, Maria, was claiming $4,000 in net wages and maybe $1,000 in medical expenses from a Seattle fishing company that hired her to work aboard the motor vessel Iceberg. The Iceberg was a 190-foot diesel-powered factory ship of 1400 tons that carried 250 fish processors, mostly Latinos, who worked 12 hours per day, seven days per week for $5.65 per hour plus overtime. A “contract completion bonus” of 85 cents per hour, plus reimbursement of transportation expense, was to be paid to those processors who made it to the end of the fishing season—which that year lasted until the end of March.

An 18-year-old from Eastern Washington who didn’t speak or read English, Maria worked for the fishing company from January 16th to March 11, 1999. I claimed that she had been wrongfully discharged from her job before the end of the season. The insurance company lawyer claimed Maria quit the ship to get treatment for Chlamydia.

My involvement in the case started with a phone call from a bilingual lawyer in Wenatchee on February 2, 2000. “My name is Patrick. I need some help with a maritime case. A lawyer I know over here suggested I call you. I’m with the Northwest Justice Project, a legal services agency for low income clients. One of my clients is a young woman named Maria who worked on a fish factory ship in the Bering Sea a year ago and was sent home with no pay.”

Patrick described Maria’s problem: she started having pain and leakage near her bellybutton from umbilical hernia surgery a year before. In early March 1999 she was flown from St. George Island to a medical clinic on Volcano Island. The clinic took a urine sample. Maria was examined and released to go back to work. On March 8th, after she was again aboard the processing ship, a lab report came back positive for Chlamydia, a sexually transmitted disease.

According to the medical records, the nurse at Volcano Island Clinic prescribed Doxycycline, which was available on the on the ship, but didn’t tell the fishing company what Maria’s diagnosis was. “I called the nurse last summer and got the definite impression that he did tell the fishing company Maria’s diagnosis, even though he claimed it wasn’t his idea to send Maria home. Don’t nurses have the same confidentiality requirements as doctors?” asked Patrick.

“I think so. The Hippocratic Oath applies to all in the medical profession. It gets strange when a nurse or doctor is on the witness stand. Under the state law of Washington, there is a ‘physician-patient privilege’ to protect patients from testimony against them by their doctors. R.C.W. 5.60.060 also applies to the ‘agents’ of the physician, like nurses, who are called to testify. Under federal common law there is no physician-patient privilege, but Federal Rule of Evidence 501 says that state law determines witness privileges. Go figure. No matter which court this case ends up in, however, the nurse had a duty of confidentiality to Maria.”

“This is where the dispute starts. Maria says the fishing company told her she had to get off the ship to get medical treatment. The fishing company says it was Maria’s idea to get off the ship, to get treatment for Chlamydia. Maria told me that she didn’t even know she had Chlamydia until she came to see me and I requested her medical records from the clinic on Volcano Island.”

“Didn’t she get the Chlamydia treated?”

“Not after she left Alaska. She was given some pills by the ship’s medic but wasn’t told what for. The antibiotics must have knocked it out.”

“So she never saw a doctor down here?”

“Yes, she did—for complications from the 1998 hernia surgery—not for an STD. That’s why I’m calling you. Let me finish the story. On March 11th the captain of the Iceberg told Maria through an interpreter that she had to go home to get treated for some serious medical problem he didn’t explain. The captain told her that the company would pay her way back to Washington and give her wages to the end of the contract. He handed her some papers written in English and told her to sign. After she signed, the co-worker who was interpreting told Maria that the papers said she was not entitled to transportation or future wages due to the nature of her medical condition. Maria tried to talk to the captain but he wouldn’t have anything to do with her after that.

“The company bought Maria a ticket to Seattle,” Patrick continued, “deducting the airfare from her earnings. There was some kind of mix-up in Anchorage, where she changed planes, and Maria was stuck there for 36 hours with no money. She finally got to Seattle and somehow made it home to Brewster. When the settlement for her pay was mailed to her house at the end of the season, she didn’t get a check. The deductions—mostly transportation—ate up all her wages, including overtime. The settlement stated her net wages as a negative figure—she owed the company money! Other than advances of a few hundred dollars, Maria was paid nothing for working a month-and-a-half, twelve hours a day, seven days a week. That’s why she came to see me. I’ve been dealing with an insurance adjuster for months. Today she refused to pay Maria anything, saying Maria had an STD and chose to leave the ship voluntarily.”

“Who’s the insurance adjuster?”

“A woman named Laura. She works for an outfit called Club Pole.”

“I know who she is. How did Laura know about Chlamydia? I thought the fishing company claims the nurse didn’t reveal Maria’s diagnosis?”

“She said she found out from a bill sent the fishing company by the clinic on Volcano Island. She also wrote me that, before the fishing company knew about Chlamydia, the nurse said to curtail Maria’s contact with other people, quote, ‘out of concern for spread of this unnamed condition’, unquote. I think the fishing company knew about Chlamydia and is trying to protect its source—the nurse. “

“Was Maria ever declared not-fit-for-duty for her hernia problem?”

“No. A doctor in Omak treated the hernia repair site with xylocaine during a brief visit last April. Other than some follow-up visits with a second doctor, that was it. Maria is fine.”

I paused to think. “You’ve got a tough one here, Patrick. I don’t think there’s anything I can do. In the eyes of the law Maria is a ‘seaman’ because she was working on a vessel in navigable waters. An STD is the kiss of death to a claim for wages, maintenance and cure under the maritime law—no matter how a seaman gets the STD in the first place. Although Maria had complications from a hernia repair, that’s not why she got off the ship—and the hernia problem never disabled her from work. Even though the fishing company is feigning ignorance about Chlamydia, and even though the captain acted badly when he told Maria to leave, getting off a ship to get treatment for a venereal disease means no unearned wages. And if we prove the fishing company knew about Chlamydia, it will try to prove it acted reasonably under the circumstances. That means showing it had reason to believe that Maria was sleeping around. That involves, in turn, delving into her sexual behavior. I don’t relish the thought of a 19 year-old Latina being grilled on her sexual history and habits by some drooling, middle-aged male insurance defense lawyer.”

“You mean that the maritime law punishes Maria simply because she’s got an STD? That’s absurd! That approach will lead to the spread of STDs, not their prevention. Public health policy now is to prevent the spread of disease, not to penalize those who have it.”

“I agree with you, but the maritime law goes back a millennium. Until very recently crews were all male. Contracting an STD meant a seaman was misbehaving ashore, just like getting drunk, and is considered misconduct.”

“But this ship had a co-ed crew living in confined quarters for a long period of time in the Bering Sea. Of course there will be sexual relations. How about the guy who gave Maria Chlamydia? Blaming it just on her is sexist.”

“You raise an interesting question. The fishing company owes its employees a safe place to work. Does that include a workplace that is free from sexually transmitted disease?”

Patrick was causing me to question some long-held assumptions. May it be legally assumed that employees in confined workspaces will engage in sexual relations? Unprotected sexual relations? If the fishing company found out that Maria had Chlamydia, did it have reasonable grounds to believe that she was sexually active with other employees? Even if it did, is such a presumption legally permissible?

“You’re opening Pandora’s Box, Patrick. I agree the maritime law is out of step with the times, but this is not the case to change it. Once the fishing company found out about Chlamydia, no matter how it found out, that arguably triggers a duty to keep other employees safe. And, talking about public health policy, what was the nurse’s duty when he found out that Chlamydia is aboard a factory ship?”

“But who’s to say Maria was sleeping around? What if she only had one sexual partner?”

“Then the question would be: ‘Where did her partner get Chlamydia?’ I’m sorry, Patrick, but I think if we pursue this case we’ll flat-out lose.”

The conversation ended.

I got another call from Patrick a month later: “I just got a copy of a letter from Dr. Kildare to the insurance adjuster about Maria and wondered if it might change your decision on taking this case.”

“Who is Dr. Kildare? And why is he writing a letter to Laura—were you involved in this?”

“Dr. Kildare is one of the Omak doctors who saw Maria for her hernia problem after she got back from Alaska. I guess the insurance adjuster wrote him a letter. The doctor sent me a copy of his response. Let me read it to you.”

“Wait a minute. Laura didn’t send you a copy of the letter she sent Dr. Kildare? Did you give her permission to correspond with your client’s doctor directly? Did she send you a copy of his response?”

“No. No. And no.”

“This stinks. It’s improper for insurance adjusters—and lawyers—to have private contact with any doctor treating someone who’s got a claim against them, the more so when that person has a lawyer to protect his or her interests. And Laura knew you represented Maria. What did Dr. Kildare tell Laura?”

“He gave an answer she didn’t want to hear. The adjuster sent Dr. Kildare chart notes from the nurse in Alaska and asked him to confirm that Maria got off the ship because of an STD, not because of her umbilical hernia problem. I’ll quote the doctor’s letter: ‘Based on the information you have provided, yes I do believe her medical complaint was related to her umbilicus and not a reproductive problem.’ John, I’ll send you a copy of this letter.”

“Wow! That does change things. Because Maria’s departure from the vessel was not because of an STD, she is entitled to maintenance, wages and cure under the general maritime law. Now I can help you. Send me her file.”

After reviewing Patrick’s file on Maria I drafted a Complaint and filed suit against the fishing company in federal court in Seattle. The Complaint alleged that Maria was entitled to have her medical bills paid and to be paid wages to the end of the fishing season, either as compensation for wrongful discharge, or as unearned wages. Unearned wages are part of a seaman’s entitlement to maintenance and cure, a no-fault remedy following illness or injury manifesting while in the service of the ship. I asked Patrick to get admitted to practice in federal court so we could be co-counsel. I expected that the insurance company lawyers would note a lot of depositions east of the mountains—they get paid by the hour—and wanted him to stand in if I couldn’t get over there. The next month I drafted a motion for partial summary judgment under court rule 56. I asked the federal judge assigned to Maria’s case to declare that she was entitled to some amount of maintenance-wages-cure based on Dr. Kildare’s letter to the insurance adjuster, the exact amount to be determined at trial.

A partial summary judgment motion is used to request that part of a case get decided “summarily”, without waiting for trial. I wanted to flush out the fishing company’s “misconduct” defense early on. In my motion I argued that Maria was fired for having an STD, based on the impermissible assumption that she was sleeping around.

To support my motion I relied upon a federal trial court case in Florida involving AIDS. EEOC v. Dolphin Cruise Lines, 945 F.Supp. 1550 (S.D. Fla. 1996). That case concerned a performer who was HIV positive, and who had been offered a job aboard a cruise ship as entertainment director. The cruise line later refused him employment, assuming that HIV would be spread to passengers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued the cruise line, arguing that it could not legally assume that the entertainer was a direct threat to himself or others. In other words, it was not legally permissible to assume the entertainer would spread HIV. The federal trial court agreed with the EEOC and ruled that it was discriminatory to assume the entertainer would spread HIV to passengers.

Appearing to defend the fishing and insurance companies against Maria was a middle-aged white male lawyer, a partner at a large firm in a downtown high-rise building. However a young associate, Jill, would be doing all the work. Jill opposed my motion by submitting hearsay statements, normally not admissible into evidence.

The fishing company claimed the nurse in Alaska, “strongly recommended that (the fishing company) curtail Maria’s contact with other employees out of a concern for spread of the unspecified condition... (The nurse) also recommended that Maria return home immediately for treatment... (The fishing company believed that) this was an urgent situation that needed prompt attention to ensure the safety of Maria and the rest of the crew.”

The fishing company swore ignorance about Chlamydia, and claimed to have sent Maria home to prevent irreversible damage to her from this “unspecified condition”. The judge denied the motion, apparently on the strength of evidence submitted by the fishing company. STD was still in the case.

“Why did the judge deny your motion?” Patrick asked me on the phone. “Their only evidence was hearsay about what they claim the nurse said. None of that was in the medical records.”

“I was surprised, too. I don’t know what the judge was thinking. I didn’t think the mere mention of an STD was the kiss of death. Maybe he views ruling on summary judgment motions as a ‘negative discretionary function’—in other words, any discretion is used against granting summary judgment, saving all issues for trial. (I sure wish he’d used ‘negative discretion’ before some of my other cases got thrown out of court on summary judgment.) Anyway, we’re stuck with his decision. Let’s get rolling with discovery. I’ll send out interrogatories and requests for production. We’ll see what they claimed to have known, and when.”

“OK. I’ll call Maria and translate the judge’s decision.”

Discovery is used to “discover” the other side’s case before trial, and is supposed to be a step up from ‘trial by surprise’ in the old days—like on the TV show, Perry Mason. I sent written discovery to the fishing company—via Jill—asking about Maria’s pay, medical attention, and what it knew about her condition.

The responses to my discovery questions were interesting: When Maria first asked for medical attention for the 1998 hernia surgery, before anyone knew about Chlamydia, the fishing company requested the clinic on Volcano Island to give her a drug/alcohol screen based upon suspicion of usage.

“That’s the first I’ve heard of drugs or alcohol,” I thought while reviewing the document. “The fishing company was already looking for a misconduct defense to avoid paying Maria wages to the end of her contract.”

The urine sample was collected on March 2, 1999. On March 5th, after Maria was back aboard the Iceberg, it came back negative for drugs and alcohol, but positive for Chlamydia. Over $2000 had been deducted from Maria’s wages, mostly for airfares but also for the medical examination on Volcano Island—including the urine test. She netted $500 in wages for the last half of January. For the month of February and the few days Maria worked in March, deductions exceeded earnings by $300.

Maria left the ship on March 11,1999. In answer to one of my interrogatories the fishing company stated: “It was not until long after plaintiff left (the ship) that defendant learned that the diagnosis was Chlamydia.” On March 6th an invoice for the urine sample was sent by mail from the Aleutian Islands to the fishing company’s Seattle office for, “culture, Chlamydia . . . $89.00”. The nurse’s chartnotes for March 8th read that he, “didn’t discuss nature of infection” with the fishing company; prescribed Doxycycline, and the fishing company told him that the information would be relayed to the vessel. There was no mention of Maria going home. Also on March 8th the Iceberg’s medical logbook contained the following entry: “Doxycycline prescribed to Maria by medical clinic,” per Seattle office. Office “also requested that she abstain from physical contact.” On March 11th a chartnote from the fishing company said it was Maria’s decision to go home for further treatment.

“Did you get a copy of discovery from the defendant?” This time I called Patrick.

“Yeah. The fishing company is lying about what it knew and when it found out. It’s protecting the nurse. The only way Maria could have known about Chlamydia when she got off the ship is if someone told her. The nurse never talked to her after she left Volcano Island on March 3rd. The fishing company is playing dumb. Maybe the nurse is lying too?”

“You’re right, the chartnotes are leaving out some information. Something happened between March 8th and 11th that tipped off the fishing company. I don’t know if we’ll ever get to the bottom of exactly who said what to whom.”

Jill started her own discovery plan. She scheduled depositions east of the mountains, to take place during September 2000, for Maria and the two doctors in Omak. Before that, she wanted to take the nurse’s deposition in Alaska.

I hadn’t met Maria and was worried how she would hold up during a deposition, given what Jill was duty-bound to ask—questions delving into her sexual behavior. Before the nurse’s deposition I drafted another motion concerning the type of questions that would be allowed during Maria’s deposition.

I argued that sexual questions had no relevance because the case was only about maintenance, cure and unearned wages. Dr. Kildare wrote that Maria got off the Iceberg because of a hernia repair problem, not an STD. I pointed out that if the fishing company pushed the issue on how Maria contracted Chlamydia it would force the plaintiff to claim that the presence of an STD made the workplace unsafe and request additional damages for contracting Chlamydia.

I used two court rules to support my motion to limit the questioning: Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 30(d)(3) allows a lawyer to stop a deposition, for long enough to get a court order, when opposing counsel uses questions to unreasonably “annoy, embarrass, or oppress” a witness. FRCP 26(c)(4) provides for a protective order by a judge about the manner in which any discovery is conducted.

Jill opposed my motion. She claimed a defense of willful misconduct, based upon Maria having an STD, and that her sexual activities were relevant. She also talked about a counterclaim against Maria for spreading Chlamydia on the vessel. Her legal memorandum, in the next paragraph, stated that, “any damages arising out of such diseases”, were simply not recoverable. I thought Jill was confused.

The judge later entered an order that any inquiry into Maria’s “sexual activities, history and habits”, in her deposition be limited to the period between mid-January and early March 1999, but that Jill could ask if Maria knew she had Chlamydia before she boarded the Iceberg.

“The judge ‘cut the baby in half’, dammit!” I muttered to myself while preparing for the nurse’s deposition. “Even allowing mention of an STD might be tough on Maria, to say nothing of allowing irrelevant and inflammatory subject matter into what should be a simple wage claim.” But I also knew I was partly at fault for the ruling. The STD gained relevance once I used it to threaten a claim for an unsafe workplace.

Jill knew she was in trouble

about proving it was Maria’s idea to get off the Iceberg. I got the

impression she was shifting gears and wanted to show that Maria was

told to get off the ship for her own good—by the fishing company,

and perhaps the nurse as well—before Chlamydia caused permanent damage

to her reproductive system. I e-mailed a doctor I knew and requested

a crash course in the treatment of Chlamydia.

The day before the nurse’s deposition, I returned to my office from a deposition in another case. “A woman from Anchorage has been frantically trying to call you all morning about the nurse’s deposition in Maria’s case.” Maura, my assistant, usually knows what’s going on in my practice better than I do.

“Who is she?”

“Her name is Janice. She said she’s the Anchorage claims manager for an insurance company that has something to do with the medical clinic on Volcano Island.”

“What did she want?”

“She asked, ‘What the hell is this deposition all about?’ She was pretty excited. I said you’d call her when you got back. “

Janice and I traded phone messages but didn’t make contact until the next morning, a few hours before the nurse’s deposition.

“What’s this about!” Janice said she was with the medical malpractice insurance company that covered the nurse’s medical clinic. “Why was the clinic faxed a subpoena duces tecum by a lawyer named Jill for the records of your client?”

“This is a lawsuit involving my client’s medical condition.” I tried to be patient.” Jill wants to take the nurse’s deposition to ask what the fishing company was told about her condition. I agreed to the deposition and stipulated to the release of medical records.”

“I won’t agree to the release of medical records! That’s confidential.”

“Maria signed a consent form for the release of medical information.”

“That form doesn’t describe her specific condition. I won’t let the clinic honor it.”

“OK. That’s Jill’s problem, not mine. Just so you know, however, both Jill and I already have the medical records from earlier requests.”

“I won’t agree to release another set of records to be an exhibit to the deposition this afternoon.”

“Fine.” The conversation ended.

That afternoon I called Volcano Island to participate in the nurse’s deposition. Jill was already there, waiting with the nurse and a court reporter. The dispute with Janice over medical records had not erupted until Jill was already in Alaska, and caused a tempest in a teapot.

Unable to appease Janice’s technical demands showing Maria’s consent to a waiver of confidentiality, Jill finally just used her own copy of the clinic’s medical records as an exhibit and the deposition proceeded on schedule.

I felt ready for the deposition, no matter what Jill could get the nurse to say. The doctor with whom I’d consulted advised that, in its early stages, Chlamydia could be treated with antibiotics alone and that there was no reason for Maria to stop working. Even in the advanced stages of Chlamydia, risk of sterility is no greater at sea than on land.

The court reporter at the Volcano Island clinic had the nurse raise his right hand and swear to tell the truth. The deposition started.

After background questions about the nurse’s training and experience, Jill got to the point. “Do you know how Maria got Chlamydia?”

“No,” the nurse responded.

“Okay, do you know whether or not she had a history of Chlamydia?”

“No, I don’t.”

“Okay. Now, did you tell (the fishing company) that Maria had Chlamydia?”

“No, I did not.”

“And why, why not?”

“Because of the confidentiality issue, I didn’t have her consent to release this information.”

“Okay. Did you ask (the fishing company) to restrict Maria’s contact with other people?”

“I don’t recall telling her that, no.”

“Did you tell (the fishing company) that if Maria’s condition was not treated, she could have permanent irreversible damage?”

“I don’t think I discussed really any of that with (the fishing company).”

“Okay, is it possible that you did and you don’t recall it, or do you believe that you did not discuss it?”

“I don’t believe I discussed that.”

“Okay. Did you recommend that the fishing company tell Maria to return home for treatment?”

“No, I did not.”

“Did you tell (the fishing company) that Maria’s condition was not related to her work on the boat?”

“No, no, I didn’t.”

“Do you have an opinion as to whether or not her condition would pose a danger to the fish product on board the vessel?” Jill was starting to sound a little desperate.

“No, I don’t think it would.”

“Do you recall having a telephone conference with (the insurance adjuster)?”

“It may have happened. I don’t recall it.”

“Did you tell (the insurance adjuster) that Maria had a history of venereal disease?”

“I don’t recall the conversation, but I doubt I told her that.”

“Okay. Do you recall telling (the insurance adjuster) that as long as Maria kept her clothes on, she wasn’t a medical threat to the fish product…?”

“That—that seems a little far-fetched, but no, I didn’t say that.”

Jill finished. It was my turn to ask questions.

“If Doxycycline was aboard the vessel, could Maria have safely kept working?”

“It would have been appropriate for her to continue working, yes.”

“Do you have any idea how long it normally takes mail to get from Volcano Island to Seattle?”

“It depends on the time of year. It could be from two days to two weeks, to maybe never.”

“Did you ever tell Maria she had Chlamydia?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Do you know if anybody else ever did?”

“No, I don’t know if they did.”

“If someone had Chlamydia and they were taking Doxycycline, would their risk of infertility be any greater on land than at sea?”

“I don’t think that makes a difference, where you’re at.”

“That’s all the questions I have.”

The deposition ended.

“The nurse didn’t say what Jill wanted him to!” I called Patrick after the deposition. “He wouldn’t say that Maria was pulled off the ship for her own good, like I feared he would. He said he’d told no one about Chlamydia. I was loaded for bear, but didn’t have to fire a shot. Jill’s trip to Alaska was for naught.”

“That’s his third version of events.”

“What do you mean?”

“The first time, on the telephone—to me and probably the fishing company as well—the nurse talked about Chlamydia. The second version is what he wrote in the medical records. You just heard the latest version.”

“That might have been influenced by the claims manager from Anchorage. She probably told the nurse: ‘Listen boy, if you want malpractice insurance renewed at this clinic, you’d better shut your mouth!’ To achieve a just result one sometimes must travel a circuitous path. Maybe we have an insurance-type to thank for saving Maria from a different insurance company…? I don’t know what happened. All I know is that the fishing company was bound and determined to get Maria off that ship. I also learned the insurance adjuster went behind your back again. She called the nurse to request an opinion last January, in private, when she knew you represented Maria.”

“Maybe the fishing company put two-and-two together between March 8th and 11th last year, assumed Maria was a loose woman and kicked her off the ship…?” Now Patrick was guessing.

“Or maybe that March 6th lab bill for Chlamydia testing got to the fishing company and was sent to the insurance company for payment, before March 11th. Laura would have time to lean on the nurse and get more information…? How did Maria get Chlamydia, anyway?”

“She said her only sexual partner is her boyfriend. He works on the Iceberg.”

“I wonder where he got Chlamydia...?”

I called Patrick two months later. “Jill has been pulled off the case.”

“Why?”

“Not sure. After the nurse’s deposition in Alaska she canceled the September depositions in Omak and said she wanted to settle. That’s the last I heard from her. A senior associate named Carl called and said he was taking over. I asked if his client(s) wanted to continue hemorrhaging attorney fees in a losing battle. I said that if he didn’t get some money to Maria pretty soon I would ask the judge to reconsider his ruling on summary judgment, based upon the nurse’s deposition.”

“What did he say?”

“Carl said that he was trying to walk through a ‘settlement minefield’, with a lot of wounded egos who felt ‘threatened’ by his recommendation to give Maria some money to settle the case.”

Two months after that the case did settle. Maria was paid $4000 in net wages, maybe $1000 in medical bills, and a little bit more for attorney fees.

John Merriam is a lawyer practicing in Seattle. He practice is limited to commercial fishermen and other seamen on wage and injury claims.