|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

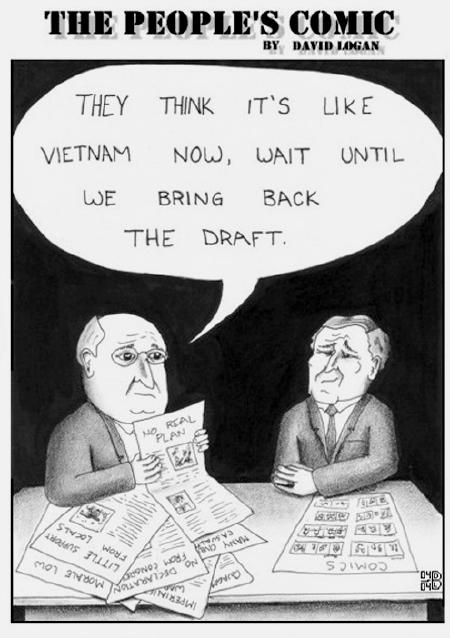

by Norman SolomonIraq Media Coverage: Too Much StenographyNot Enough CuriosityCuriosity may occasionally kill a cat. But lack of curiosity is apt to terminate journalism with extreme prejudice. "We will not set an artificial timetable for leaving Iraq, because that would embolden the terrorists and make them believe they can wait us out," President Bush said in his State of the Union address. "We are in Iraq to achieve a result: A country that is democratic, representative of all its people, at peace with its neighbors and able to defend itself." President Johnson said the same thing about the escalating war in Vietnam. His rhetoric was typical on Jan. 12, 1966: "We fight for the principle of self-determination--that the people of South Vietnam should be able to choose their own course, choose it in free elections without violence, without terror, and without fear." Anyone who keeps an eye on mainstream news is up to speed on the latest presidential spin. But the reporters who tell us what the president wants us to hear should go beyond stenography to note historic echoes and point out basic contradictions. A couple of days before the voting in Iraq, the lead story on the front page of the New York Times--summing up the newspaper's exclusive interview with President Bush--had reported his assertion "that he would withdraw American forces from Iraq if the new government that is elected on Sunday asked him to do so, but that he expected Iraq's first democratically elected leaders would want the troops to remain." Logically, the president's statement should have set off warning buzzers--along the lines of "What's wrong with this picture?" For instance: Public opinion polls in Iraq are consistently showing that most Iraqis want US troops to quickly withdraw from their country. Yet Bush asserted that the Iraqi election would be democratic--even while he expressed confidence that the resulting government would defy the desires of most Iraqi people on the matter of whether American military forces should remain.

The easy way for journalists to reconcile this contradiction is to ignore it--a routine approach in news reporting. Military power has a way of creating some political constituencies for itself. And that is certainly true of the Pentagon's massive footprint in Iraq, where the Jan. 30 voting was part of a mystified process--with a US-selected election commission and ground rules that kept candidates' political stances, and even their names, mostly secret from the voters. In the coming months, the potential for a disconnect between voters and the policies of the new government's leaders is enormous. Since last summer, the leadership of the "interim" government in Baghdad has been largely comprised of Iraqis opting to throw their lot in with the occupiers. At this point, their hopes for power--and perhaps their lives--depend on the continued large-scale presence of American troops. Naturally, the current prime minister Ayad Allawi, installed by the US government last June, now claims the insurgency will be defeated if the American troops stay long enough. Even President Ghazi al-Yawer, who has been critical of some aspects of US military operations in Iraq, is now touting the need for Uncle Sam's iron fist. As February began, al-Yawer declared at a news conference: "It's only complete nonsense to ask the troops to leave in this chaos and this vacuum of power." Writing in the Boston Globe of Feb. 1, columnist James Carroll put his finger on a key dynamic: "The chaos of a destroyed society leaves every new instrument of governance dependent on the American force, even as the American force shows itself incapable of defending against, much less defeating, the suicide legions. The irony is exquisite. The worse the violence gets, the longer the Americans will claim the right to stay. In that way, the ever more emboldened--and brutal--'insurgents' do Bush's work for him by making it extremely difficult for an authentic Iraqi source of order to emerge." Meanwhile, the London-based Guardian published a devastating essay by a university lecturer who left Iraq during Saddam Hussein's rule. Sami Ramadani wrote: "On Sept. 4, 1967, the New York Times published an upbeat story on presidential elections held by the South Vietnamese puppet regime at the height of the Vietnam War. Under the heading 'US encouraged by Vietnam vote: Officials cite 83 percent turnout despite Vietcong terror,' the paper reported that the Americans had been 'surprised and heartened' by the size of the turnout 'despite a Vietcong terrorist campaign to disrupt the voting.' A successful election, it went on, 'has long been seen as the keystone in President Johnson's policy of encouraging the growth of constitutional processes in South Vietnam.' The echoes of this weekend's propaganda about Iraq's elections are so close as to be uncanny." During the first days after the balloting in Iraq, few discomfiting facts have intruded into mainstream coverage in the United States. But the fairytale storylines that have sailed through the reporting and commentary will soon run aground onto hard reefs of reality. The US government is set to keep large numbers of troops in Iraq for a long time to come. And no amount of thunderous applause and media praise for State of the Union verbiage can change the lethal discrepancies between democratic rhetoric and military occupation. Norman Solomon's next book, War Made Easy: How Presidents and Pundits Keep Spinning Us to Death, will be published in early summer by Wiley. His columns and other writings can be found at his website. |

|