|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | Do Something Directory | ||||

|

||||

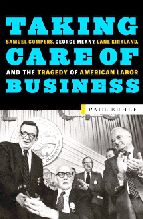

Unions: Taking Care of Workers?Taking care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland and the Tragedy of American Laborbook by Paul Buhlereview by Brian King

But so what? If you can imagine an America without weekends off, overtime pay, or health care coverage, then you can start to imagine what life would be like in these United States without a politically effective labor movement. The New Deal could not have happened without the powerful and reliable support of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CIO took to the streets and remade the Democrats in the 1930s into a party that would pass Social Security, Medicare, the Voting Rights Act and much more. Besides, if you're like most people and you have to work for a living, it's great to have a union! Especially when it's time to speak up about something your boss doesn't want to hear. So why are unions on the decline if they're so great? Academic observers tend to emphasize the role played by our transforming economy. These days there are a lot fewer of the blue collar industrial jobs that we associate with big unions. Labor organizers emphasize the disadvantages for organizing built into our labor laws. These laws make organizing drives in the US a lot like making the workers walk back and forth over a bed of hot coals to make sure they really want a union. But, as with any issue this large and complicated, there are many ways to look at why unions are on the decline in the US. Paul Buhle offers an historical approach to this question in his 1999 book, Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland and the Tragedy of American Labor. Buhle uses the careers of US Labor's three principal 20th century leaders as lenses through which to examine the unions and try to understand their many failings. Taking Care of Business looks at labor and American history from a left, socialist point of view. The book begins with a series of stated or implied questions:

For someone who cares about unions, the narrative is often painful. The descriptions of Gompers, Meany, and Kirkland are unflattering, to put it mildly. But, given their obvious drawbacks, what did place these three men at the head of one of the world's most powerful and important labor movements? For an answer to that question, we return to the four questions stated above, and to a concept often referred to in writings on US history, "American Exceptionalism". This refers to the opinion of many that America is the exception to the rule that industrial societies generate powerful, democratic unions and effective social democratic political parties that stand for the rights and needs of working people. In this well-thought-out book, Buhle offers two principal reasons for why America and American unions are different. For one, Buhle believes that America's position in the world, that of top dog or nearly top dog for the last 150 years, has been a considerable distraction for US workers. When your bosses are calling the shots in everyone else's country, there's a good chance you're in line for a soft seat and a short oar. Why worry about having a union? More important than America's role as dominant power, for Buhle, is the poisonous and corrosive nature of racism in the US. Race hatred and discrimination have been powerful in America because of their historical roots in the vicious form of slavery practiced here, and because of the striking differences in physical appearance between black and white. Race has been used to divide workers' movements, such as historically when white workers tried to strike, and their boss would bring busloads of willing African-American workers in to scab on them. This has happened in America many, many times. The malignancy of anti-Communism is tied to the US status as the dominant power in the world . This was used to decimate the leadership of US unions after World War II. During the McCarthy years, the unions were bullied into expelling anyone suspected of communist ties. Most of the best, committed, and experienced union organizers were eliminated this way. As an antidote to the business-friendly unions that emerged from the McCarthy era, Buhle suggests an emphasis on what is called "social unionism". Many of our big unions are making serious efforts to become social unions. They are genuinely trying to eliminate racism, sexism, and homophobia as decisive factors in how jobs are distributed and leadership is determined. And, many unions are forging ties in their respective communities around such issues as raising the minimum wage. Buhle singles out for special praise the 'New Voice' leadership under president John Sweeney, that was elected at the at the 1995 AFL-CIO convention. The Sweeney victory emerged from under the thick cloud cast by the 1994 Gingrich-Republican sweep in the congressional elections. It promised a sharp turn toward organizing non-union workers as a way of strengthening the unions ability to stand up to the Republican onslaught. It would certainly help if a lot more workers were organized into unions. And it's easy to agree with Buhle's emphasis on social unionism. But it's hard to ignore the near absence of discussion in this book about another glaring need the labor movement should address in order to get itself back on the organizing road. American unions contain many thousands of amateur member-organizers. They could be mobilized in a monster drive to bring, say, Wal-Mart into the union camp. Wal-Mart workers, like most everybody in advertisement-saturated America, find it easier to believe what someone is telling them if it's from his/her heart. If you are there on your day off, you must be saying the "straight stuff." Besides, it's never going to be possible to hire enough professional organizers to talk to even a small fraction of the unorganized in the US Along with becoming good social unions, American unions need to mobilize their rank and file members to rebuild the union movement! Paul Buhle's book is highly recommended. Anyone who wants to attain an understanding of where our unions have been, and where they might go, should read Taking Care of Business. |

|

The sad tale of the slow, steady decline of the labor movement in the US

is a familiar one to Americans these days. Most activists agree that it

doesn't paint a pretty picture for the future of change toward a more

just, fair, and equal society. It's hard to say what portion of the

working class (often referred to as 'union concentration') this drop in

membership needs to reach before organized labor is simply no longer

able to defend itself, but many friends of the unions fear that we're

not far from such a point. Unionization is down from 35 percent of the

working class in the 1950s to 13 percent today. If government workers

are excluded, it's a little under 10 percent.

The sad tale of the slow, steady decline of the labor movement in the US

is a familiar one to Americans these days. Most activists agree that it

doesn't paint a pretty picture for the future of change toward a more

just, fair, and equal society. It's hard to say what portion of the

working class (often referred to as 'union concentration') this drop in

membership needs to reach before organized labor is simply no longer

able to defend itself, but many friends of the unions fear that we're

not far from such a point. Unionization is down from 35 percent of the

working class in the 1950s to 13 percent today. If government workers

are excluded, it's a little under 10 percent.