|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

|

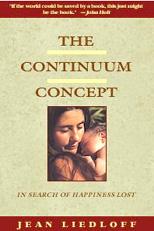

My Favorite BookWhat's your favorite book? Write about it!Dear Readers: Is there a book that has just grabbed you for years? Do you find yourself frequently talking about a certain book to friends and people you meet? What book do you wish many other people would read? Please submit a review including (1) a description of such a book, and (2) an explanation of why you like it so much. Some ground rules: you should have no personal or commercial connection to the publisher or writer of the book, and your article should be not more than about 800 words long. Please submit electronically to WAfreepress@gmail.com along with your name and phone number (we will not use your contacts for solicitation). Writing in the Washington Free Press is volunteer. We encourage you to be a subscriber to the paper, though that is not required. The Continuum Concept: in search of happiness lost(also titled The Continuum Concept: allowing human nature to work successfully)by Jean Liedloff first published 1975 review by Doug Collins

If I told you that this book was written by an American woman who stayed a few years with primitive Indians in the Venezuelan jungle, that might lead you to believe that it is a typical anthropology book. It definitely isn't. Although Jean Liedloff describes the culture of the Indians she lived with, especially their child-rearing practices, her book becomes mostly a stinging criticism of our own modern culture. Liedloff's first-hand accounts of life in a Yequana village provide an external viewpoint from which one can soberly look at modern cultural practices. Liedloff, for example, noticed that there was no sibling rivalry among the primitive children she lived with, no temper tantrums among toddlers, and that among adults there was a very deep social security within the small village, with great tolerance for individual differences, and a joy in doing any sort of work together. In short, the Indians she lived with were paragons of mental well-being and happiness. (One must keep in mind that these were Indians who were still little-touched by outside technology or modernization: mental illness is, of course, notable among modernized Indians in Venezuela and elsewhere.) What basically separates our culture from that of the primitives, according to Liedloff, is that they have a "continuum", a comforting combination of culture and environment that continues with each generation with very little change. Because modern society has lost such a continuum, modern people are typically seeking happiness, as though it is some sort of external goal that they might reach in the future. On the practical level, Liedloff provides explanations for how the continuum is promoted or disrupted by childrearing practices. One practice of the primitive women is to be in constant physical contact with newborns for at least the first three months of life: no cribs, no strollers, no car seats, always carrying and sleeping with the baby. Liedloff postulates that the modern practice of keeping infants often separate from the mother creates a deep-seated unsatisfied feeling in modern people when they grow up, which becomes the source of many modern neuroses, such as our incessant search for novelty, focus on material acquisition, tendency toward drug addiction, and others. Another practice that Liedloff noticed is that the primitive adults do not even pay much attention to their kids. The adults instead are the focus of the children, who are usually following the adults, watching their activities, and often imitating them. She contrasts this with modern parents in a park, who are usually chasing after their toddlers. She points out the unnaturalness of modern "child-centered" practices, because when children become the focus of attention, they miss the practical examples of behavior that adults should be providing. Many modern adults are looking for answers in their children, but the children don't really have them, a strange relationship which leads to frustrated temper tantrums, generation gaps, and the loss of the continuum. I have found myself often mentioning Liedloff's book to others. I like the book not only because it provides insight into child-rearing ( I have two small kids), but also because it explains so much of human nature in one rather short swoop (172 pages paperback), including keen insights on the nature of work. The Continuum Concept has profound political and environmental meaning, but it transcends any modern political or environmental analysis that I've ever read. In terms of philosophy, it might be described as both radical and reactionary at the same time, but it is beyond either of those categories. For me, this book has provided a reasonable diagnosis of why "advanced" and "developed" modern societies are really so ill and so unsustainable. Another aspect of the book I appreciate is Liedloff's writing style. When I first opened a random page, I felt as though I was propelled by a current of water. The feeling is a bit like reading Jack Kerouac, but without any stylistic concern: Liedloff is writing out of feverish fascination with her topics, and the keenness and beauty of her observations brought me to tears more than once in reading her book. That's pretty rare for nonfiction. Curiously, although Liedloff remains active in child-rearing issues, this is the only book she has written, and that some 30 years ago. Some more recent essays are available on the internet at www.continuum-concept.org. After reading this book a few years ago, I learned that it had become the origin of the Attachment Parenting movement, the modern movement centered on providing closer mother/baby contact, including co-sleeping and breastfeeding. So in some ways, I and my family had already been affected by the book prior to reading it. But it seems to me that most current "attachment parents" have never heard of this book, and would probably benefit from reading about how "attachment" is not just using a baby sling when you walk in the park. On the other hand, Liedloff herself mentions that if she told the Venezuelan Indians that parents in the "developed" world learned about child-rearing from reading books and magazines, the Indians would only laugh uproariously.* |

|