|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

|

In the US, many of us were educated as children with the mantra of "We're Number One." But when you learn more about other countries, you see that they are often superior in various ways. It's time we start to better appreciate this. If you've traveled or lived outside the US, the Free Press invites you to contribute to this column. Appreciating the Bitterpart 1: Should the poor orphan child really be saved by a miracle?by Doug CollinsIt occurred to me recently that the desire for sweetness is an especially American characteristic. A taste for sweet foods is one example. Many immigrants I've known comment on how much sugar there is in cakes and cookies in the US. And the sugar doesn't stop at desserts. Americans often add sugar to many meal entrees, and many processed food items have quite a bit of sugar where you might not expect it--just check the nutrition list on your bottle of store-bought spaghetti sauce. It's often hard to find a bottled unsweetened tea in the US, whereas in Japan or other countries it's hard to find a sweetened one. My wife noticed last summer that if you simply order an "iced coffee" at Starbucks, it is typically sweetened by the barista unless you request it not to be. Of course candy adds another dimension. From Halloween till Valentines Day, as a country we're buried in an avalanche of sugar. Large amounts of sugar--or sugar substitutes--might seem to be a random variation in culture, until you look more deeply.

First, why would there be a lot of sugar here? One reason is that sugar has preservative qualities. Because the US is geographically a large country, processed food items on average have to be shipped longer distances. And because our retail outlets have assumed huge mega-market sizes, a longer shelf-life--say for a product like boxed cookies--might be desirable. Larger proportions of sugar might assist in that. As people become accustomed to more sugar in store-bought items, they may try to reproduce the taste in their home baking. Food marketers also test various foods in focus groups, and likely find--for example--that more Americans prefer the taste of spaghetti sauce with quite a bit of sugar in it. Until all Americans become diabetic, processed food manufacturers may persist in following the marketers' advice. Another reason for more sugar is that Americans tend to be "on the go" people, and family dinners may be inconvenient or out of the question. Many people are therefore looking for quick energy, and sugar is a ready answer. Sugar is basically pure energy: calories without any pesky vitamins or minerals. The problem with eating a lot of sugar is that it satisfies your body's short-term energy needs, but it doesn't give you the nutrition you need in the long-term. It's a quick fix. In older, slower times, "sweet" was not the overwhelming choice of the American palate. California herbalist Christopher Hobbs points out that a century ago, bitter foods and tonics were prized in the US. It was a common practice here to "take your bitters." Hobbs gives examples of frequently consumed bitter foods and tonics still consumed in such countries as modern Greece and Germany (an article by Hobbs is online at www.healthy.net/scr/Article.asp?Id=862). Having lived in China for two years, I can attest to the commonness of bitter food in China and Asian cultures. If you check out Asian vegetable markets in the US, you will likely find the much-loved "bitter melon," a bumpy light-green vegetable about the size and shape of a cucumber. I suggest that you buy one, remove the pith and seeds in the middle, chop the rest into bits, and stir fry it with maybe some soy sauce and garlic. Most Americans would probably be shocked that a taste for it could possibly be acquired. But the taste grows on you, as it has on probably a billion others. Hobbs points out that bitter tastes are good for digestion, and therefore help prevent a variety of chronic disease. Excess sugar, on the other hand, creates a body that is prone to digestive disorders, diabetes, and yeast or other fungal infections.

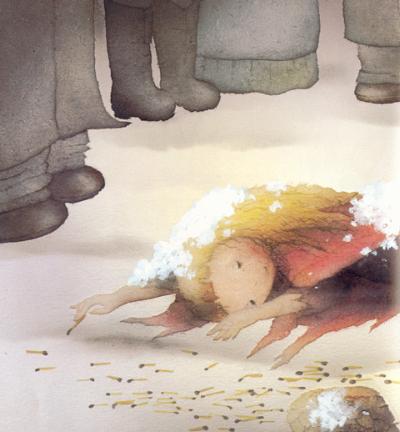

I'm tempted to believe that sugar-addiction in modern America is a sign of a deeper-seated social psychology. I say so because it parallels--in very interesting ways--at least a couple other trends in American life. First, consider the "Hollywood Ending," the sweet resolution typical of American movies. How many US film endings have been steered toward happiness by producers, over the objections of writers who had intended tragedies? One example is the movie A Dog of Flanders. The original story, by writer Marie Louise de la Ramee (pen name Ouida) from 1872, deals with classism in Belgium, and ends with the tragic death of an orphan boy and his dog, the two protagonists of the story. At least a few movie versions have been made over the past century. The 1959 American version of the movie--starring a young David Ladd as the boy--stayed true to the original ending, however a more recent American version, from 1999, contains a miraculous salvation at the last moment. Instead of a tragedy with universal meaning about the cruel foolishness of prejudice, the more recent film is just another sweet movie about a boy and his dog. My guess is that if de la Ramee were still alive, she'd probably try to neuter the producer (which is exactly what he did to her story). Significantly, a recent Japanese anime movie version titled The Dog of Flanders--produced in the year 2000 and marketed to children--contains a devastatingly tragic ending. If it doesn't squeeze a tear out of you, then you probably don't have much of a soul. I have noticed as well that books for Japanese and European children do not shy away from tragic endings, unlike almost all modern American kids' books. For example, Hans Christian Anderson's short story The Little Match Girl (also known as The Little Match Seller) is a tearjerker known to almost all Japanese children. It ends with the death of an impoverished young girl. The story is almost unknown among kids now in the US, though I came across one version printed in the 1950s and one published just recently. Do Japanese kids benefit from seeing or reading such tragedies? I think so, because tragedies stay with you, reminding you of your responsibilities toward others in society. On the other hand, if the poor orphan child is saved in the end by a miraculous twist, then the reader is released from any long-term responsibility for helping others, because--by gum--miracles always just save good people right in the nick of time. By replacing bitterness with sweetness, producers of the latest American version of A Dog of Flanders have squandered the potential of the story. By "protecting" kids from sad endings, American children's book publishers have created at least a couple generations of kids who are less likely to see their own role in righting the wrongs of society, and perhaps less able to even sympathize with victims of injustice. (The power of imagery to create sympathy is well understood by every war-making leader who seeks to suppress media images of torture and death in occupied countries.) The parallels between excessively sugary food and excessively sugary story endings are quite astounding. Both are modern phenomena. Both provide a convenient quick solution for some sort of immediate desire for comfort. Both lack long-term substance. Both sorts of sweetness, without being balanced by bitterness or sadness, may simply be unhealthy. Another intriguing parallel is that sweetness of both sorts is commonly loaded onto American kids, as though they are unequipped to handle anything unsweet. (Look how many parents are routinely feeding their kids soda now--or at best juice--as though the kids are not capable of digesting simple and healthy water.) The conclusion of this article will appear in the next issue. |

|

Asian bitter melons. Try 'em, you'll like 'em, after a year or so!

Asian bitter melons. Try 'em, you'll like 'em, after a year or so!

Tearjerker for toddlers. Page from a Japanese kid's tragic storybook

based on The Little Match Girl.

The telling of tragic tales to children in Japan and Europe may lead to

more sympathy there for people who are treated unfairly.

Tearjerker for toddlers. Page from a Japanese kid's tragic storybook

based on The Little Match Girl.

The telling of tragic tales to children in Japan and Europe may lead to

more sympathy there for people who are treated unfairly.