go to WASHINGTON FREE PRESS HOME (subscribe, contacts, archives, latest, etc.)

Jan/Feb 2000 issue (#43)

|

|

In the new film The Gambler, a great author is asked about the protagonist of his novel: is this character familiar to him? He answers "I write fiction, Miss Snitkina." It's an understandably evasive response. To suggest that a writer's only source is his own life is to diminish his creative powers -- as did Shakespeare in Love. In this case, however, the creative process is not merely material for jokes.

The Gambler moves fluidly between dramatizations of scenes from Dostoyevsky's novel of the same name, and of how the book came to be -- a great story on its own. It's a measure of how amazing the latter is that, although I'd read the book three years ago, and was familiar with the story of its writing, the outcome seemed incredible when I reencountered it here.

Dostoyevsky wrote The Gambler, as he wrote most anything, in order to exorcise inner demons and illuminate the human soul. He also wrote it because his publisher had him by the balls: unless a book were produced, the publisher would own all of Dostoyevsky's work -- past and future. Time was short, so a friend proposed a desperate experiment. Enter Anna Snitkina, star pupil at the St. Petersburg stenography school.

For the next 28 days, Dostoyevsky dictated a wickedly funny novel, narrated by one Alexei. Our hero is equally smitten with a woman and with the roulette tables. He has the misfortune to glimpse the absurdity of his own passions. Nevertheless, as Alexei himself knows, "reason alone is not enough in such matters."

At first, The Gambler appears to be typical Masterpiece Theatre fare -- only with a smaller budget. The minimal production values help convey the drabness of Dostoyevsky's quarters. The movie mostly lacks the novel's savage humor. But just because a film and a book share characters and plot, they should never be expected to produce the same set of impressions.

This film focuses on the interplay between Dostoyevsky's novel and the story of Dostoyevsky and Snitkina themselves. The writer is surly from the start, peppering her with provocative questions: "Do you think the hero will save her?" "What kind of a novel do you think this is?" Their relationship takes on aspects of artistic collaboration. As in the case of the artist and model in La Belle Noiseuse, how can their relationship not, in turn, influence the art?

Directed by Karoly Makk, the film is at its best when it segues between fiction and reality. Once, Dostoyevsky asks Snitkina, "Are you in love with him?" Then he asks it again. But no, this time it's not a question -- he's merely dictating a line from the novel. The two worlds spill together most physically in the form of Polina: a woman from the writer's past who inspired a character in the novel. When the real Polina appears, she's played by the same actress as the fictional one. Only gradually do we realize that this woman exists independently of Dostoyevsky's imagination.

As played by Michael Gambon, Dostoyevsky is a frail man of flesh and blood, not an awe-inspiring presence. Jodhi May is impressive in the role of Anna. She conveys a character who, though vulnerable, does not suffer lightly hand-kissing by fools. Luise Rainer also makes an appearance. You may recall her consecutive Best Actress Oscars -- if your memory extends back to 1937 and 1938.

In addition to Dostoyevsky's own gambling, The Gambler touches on his epilepsy and his persecution by the government -- taking some forgivable liberties with the facts in the process. Thus, there's yet another level of reality: even the story of Dostoyevsky and Snitkina is in part a fiction.

Cinematic neorealism has made a comeback. Elements of the style have appeared in such recent films as Central Station and Children of Heaven. In The City we now have such a film set not in Brazil or Iran, but New York City. This vision of New York is about as far from Breakfast at Tiffany's or even Mean Streets as can be.

| The City |

|

The film consists of four episodes in the life of Latino immigrants, and is in Spanish. Each story quickly draws us in. Director David Riker says "I hope that the film creates a solidarity capable of opposing the anti-immigrant fever that is so rampant."

The stylistic reference to Italian neorealism is a statement in itself, linking the poverty of postwar Europe with that of contemporary New York. The former was deemed worthy of a Marshall Plan. Not Mayor Giuliani's town.

This New York is a harsh, oppressive place. In a scene right out of Bicycle Thief, men clamor to be selected for work. The work turns out to be salvaging bricks -- at 15 cents apiece -- from a desolate site.

Children are a staple of neorealism -- especially the image of a child and a parent as two lonely figures in a hostile world. Thus, one story concerns a homeless puppeteer and his daughter.

Aside from the rigors of survival, the main theme of these stories is the yearning for people and places left behind. Even a new arrival, noticing how things have quieted down, says "Listen!... The city has disappeared." He can now imagine he's back home. But this is a place where the ease of getting lost, of not knowing where you are, can have tragic consequences.

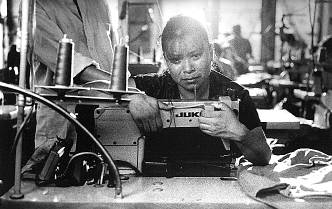

Despite the bleakness of this film, the black and white photography is starkly beautiful. The brightest ray of light comes in the final story, about a seamstress, desperate for money to help her sick daughter. There's an impromptu gesture of unity that's quite moving, as one by one the sweatshop machines are turned off.

Perhaps the most important question to ask about any film is: does it tell the truth? The City is an honest film.

These films play January 21-27; The Gambler at the Grand Illusion, The City at the Varsity.