|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

|

Becoming 'Good Americans'by Fred Branfman"Gestapo interrogation methods included repeated near drownings of a prisoner in a bathtub." --The History Place

"The CIA officers say 9-11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed lasted the longest under waterboarding, two and a half minutes, before beginning to talk, with debatable results." --Brian Ross, ABC World News Tonight, November 18, 2005

"When President Bush last week signed the bill outlawing the torture of detainees, he quietly reserved the right to bypass the law under his powers as commander in chief... Bush believes he can waive the restrictions, the White House and legal specialists said." --"Bush Could Bypass Torture Ban," Boston Globe

As a teenager, I could not understand how the German people could claim to be "good Germans," unaware of what the Nazis had done in their names. I could understand if these ordinary German people had said they had known and been horrified, but were afraid to speak up. But they would then be "weak or fearful or indifferent Germans," not "good Germans." The idea that only the Nazis were responsible for the Holocaust made no sense. Regardless of whether the Germans as a whole knew about the concentration camps, they certainly knew about the systematic mistreatment of Jews that had occurred before their very eyes, and from which so many had profited. What should or could they have done, given the reality of Nazi tyranny? The issue became personal for me in the summer of 1961, when I hitchhiked through Europe with a lovely German woman named Inge. Still in love after an idyllic summer, we visited Hyde Park the day before I was to return home. A bearded, middle-aged concentration-camp survivor was angrily attacking the German people for standing by and letting the Jews be slaughtered. I was moved beyond words. Suddenly the woman I loved began yelling angrily at him, screaming that the Germans did not know, that her father had just been a soldier and was not responsible for the Holocaust. Our relationship essentially ended then and there. I understood intellectually that she was just defending her father and was neither an anti-Semite nor an evil person. But there it was. She on one side. The survivor on the other. A gulf between them. Whatever my head said, my heart knew that the world is divided into evil-doers, their victims, and those like Inge who do not want to know. And that I had no choice but to stand with the victims. I never dreamed at that moment that I, as an American, would a few years later face this same question as my government committed mass murder of civilians in Indochina in violation of the Nuremberg Principles. Or that more than four decades later I would still be struggling with what it means to be a "good American" after learning that a group of US leaders has unilaterally seized the right to torture anyone it chooses without evidence and in violation of international law, human decency, and the sacrifice of the many Americans who have died fighting autocracy and totalitarianism.

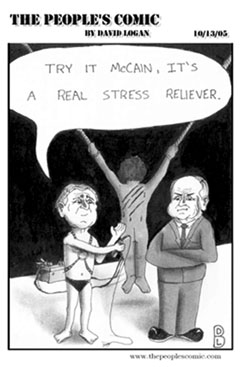

The issue has become urgent because Bush has chosen to demand the legal right to torture anyone he wishes. When torture was revealed at Abu Ghraib, the administration--falsely and shamelessly--attempted to shift its own responsibility onto foot-soldiers like Lynndie England. Since then, however, leaks have revealed that the CIA has tortured terrorist suspects all around the world, using techniques like "waterboarding." In response, Senator John McCain proposed an amendment, attached to the 2006 Defense bill, that would ban torture. Bush's first response to McCain's amendment was to threaten to veto the Defense Bill if it passed. When it became clear that McCain's amendment would pass by an overwhelming majority (it passed in by a 90-9 margin in the end), Bush reversed course and said he would support the amendment. Yet when he actually signed the bill, Bush added something called a "signing statement" in which he reserved the right to do whatever he chooses as Commander-in-Chief to "protect the American people from further terrorist attacks." In short, even as he signed McCain's amendment, Bush let it be known that he intends to ignore it as he sees fit. Bush's demand is unprecedented. No leader in all human history, not even Hitler, Stalin, or Mao, has publicly demanded the right to torture. All others have behaved as Bush did before the amendment, when he secretly tortured on a scale unseen in American history even while saying he wasn't. Forced into the open by the McCain amendment, however, Bush chose to openly demand the legal right to torture. Most experts assume he will continue to torture. As a result, we are in some ways more morally compromised than the "good Germans" of the 1930s. To begin with, we are far less able to claim we do not know. Our daily newspapers regularly report new revelations of Bush administration torture. Second, by opposing torture, we face far less severe threats than did Germans who tried to help Jews. Even the strong possibility that we could become targets of illegal spying by this administration for protesting its torture is far less frightening than the death or imprisonment faced by Germans who helped Jews. And, third, unlike the Germans, we cannot reasonably claim that it is futile to oppose our leaders. Creating or joining an organized effort to prevent torture can succeed because we possess one great advantage that human rights advocates in Germany did not have: the public is with us. Most Americans abhor torture and can understand the argument that it does not protect American lives. This is why the McCain amendment enjoyed 90 percent majorities in the Republican-controlled House and Senate, and why it is possible to bring to power leaders who are not committed to torture. If we can build a movement to limit and ultimately remove from power those who torture, and thus endanger our lives, we will be achieving other important goals as well. We will be building support for international law, which is one of humanity's few frail protections against far greater violence. If we can implement international law against torture, perhaps we can extend it to preventing the murder of civilians or aggressive war. We will be reaffirming America's once-strong commitment to building the kind of new international order that is required to reduce international terrorism, and fostering a world in which US leaders would once again be respected as fighters for human decency rather than despised as threats to it. We will bring the once-powerful but forgotten force of morality and nonviolent action--for civil rights, for peace, for women's rights--back into our politics. A false morality that claims to love Jesus while torturing and killing in his name will be replaced by an authentic morality that seeks to address the root-causes of terrorism and violence. We will thus also join this renewed moral force with a practical strategy that can actually protect us from terrorism. Torture is only the most dramatic example of how Bush has endangered our lives by bungling the war on terrorism. He has also dangerously neglected homeland security, alienated world opinion, helped Al Qaeda grow in numbers and fervor, wasted vast resources in Iraq in ways that increase terrorist ranks, failed to build an effective democracy in Afghanistan, failed to bring peace to the Middle East, and failed to address the poverty that fuels anti-American terrorism. Ending torture is a necessary precondition to developing an effective strategy that will actually protect rather than endanger Americans. And we will strengthen democracy at home. Nothing is more un-American and undemocratic than the idea that a small group of executive branch leaders should be free to torture, kill, and spy at will. This idea is in fact precisely what generations of Americans have died fighting against. Ending Bush's use of torture will be the beginning of restoring an accountable and democratic government to this nation. Whatever a movement to abolish torture will achieve for society, it is clear what participating in it means for each of us as individuals. It means above all that our children and grandchildren will not remember us with shame, that they will not one day have to try to justify to our victims our failure to oppose the torture being conducted in our names, and that the term "good Americans" will mean just that, and not become an excuse for fear or indifference. When we fight to end torture we are not only fighting for human decency, international law, democracy, and freedom. We are fighting for ourselves. Fred Branfman is a writer and long-time political activist. His email address is fredbranfman@aol.com and his website is www.trulyalive.org. He is writing a book entitled Facing Death at Any Age. A longer version of this article was originally published in Tikkun magazine. |

|