|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

|

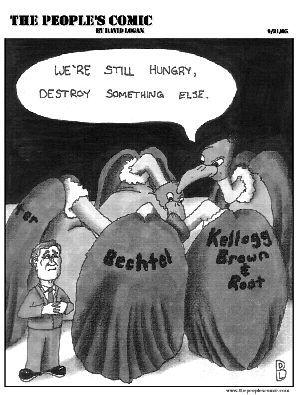

Writing in an Age of Terrorby David SwansonThe following remarks were delivered at the opening forum of the National Writers Union conference in Philadelphia in October 2005. Obviously, if this really were an age of terror, an age in which we were all terrorized, there would be no writing. You can't write if you're terrorized. I mean, you can, but your writing will have all the clarity of a campaign speech by John Kerry, or all the relevance of the election-year literature produced by the AFL-CIO, which refused to acknowledge that there was a war in Iraq. Every serious article about US or global politics that pretends there is no war in Iraq is an example of writing in an age of terror. Every article that pretends the war is not a blatant violation of international law and a crime against humanity is an example of writing in an age of terror. But that sort of writing, during other wars, predates the commandment from Bush to feel terrorized. What's new about writing in this age, I think, stems from the rule that you must be either with or against the anti-terror crusaders being led by George W. Bush. This has resulted in a new unwillingness on the part of those opposed to Bush's policies to openly say so, or to say so without all sorts of qualifications. The progressive PR firm Fenton Communications in March 2003 published a book of tips for "navigating media in wartime," which began "DON'T bash Bush. Two out of three Americans approve of Bush's handling of the confrontation with Saddam Hussein. In times of war--especially the early stages--the public's instinct is to stand behind its leader. You won't win any allies by alienating yourself with harsh attacks." Now, of course, two out of three Americans disapprove of Bush's war, but Fenton hasn't really changed its tune. In fact, everybody's singing from the same hymnal. Another progressive organization called Demos released a set of "[Hurricane] Katrina Talking Points" some weeks back that included this: "Keep the conversation in a 'reasonable mode.' Appeal to people across political ideology. This means avoiding sharp, rhetorical language about political parties, politicians, etc. Stay away from discussing particular people who are to be blamed. This is very important. When highly political, partisan or ideological images are triggered people revert to their own traditional identifications and positions and stop 'hearing' a more reasonable discussion about government and its purposes." There is absolutely nothing reasonable about self-censorship during a time of rising fascism. The right wing does not self-censor in this way, and it has not worked for Democrats over the course of my lifetime. It's not a new approach. But what strikes me as new is the degree to which ordinary activists are all modeling themselves as amateur PR strategists and all parroting the self-defeating centrist talking points put out by the people paid for that service. You can go to strategy meetings of liberal activist groups of any size, from the largest coalitions to the tiniest small-town gathering, and the discussion will focus on properly framing the message so as to appeal to those who completely disagree with us. And that framing of the message will not be about persuading people to change their minds so much as it will be about censoring parts of our message so as not to offend them. The corporate media should get a pile of blame for this. The way it shuts out voices and labels positions as unacceptable is not just manufacturing consent. It's manufacturing a million little manufacturers who go out and spread the gospel, who nominate unsatisfactory candidates because the media said they were the electable ones, and who ultimately are speaking and writing from a place of fear and terror. The question for us is not how we can write better in an age of terror, but how we can write ourselves and others into a realization that this is not an age of terror, that many many people are not scared, that a majority of us oppose Bush, oppose his war, and want to see him impeached over it, and that no matter how radical the message framers tell us that is, it is still majority opinion and we still must write about it without any fear, with complete honesty, without any modification for alleged broader appeal. Emerson said "To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men [and women],--that is genius." Conversely, then, to believe that others cannot handle your thoughts must be idiocy. That means that if you believe a war is wrong because little Arab children get their limbs ripped off, you should write that. You don't have to write that it's wrong because some veterans now oppose it. You can and should write that if that's what you believe. But I'm not convinced that we stop enough and ask ourselves what we believe.*

|

|