|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

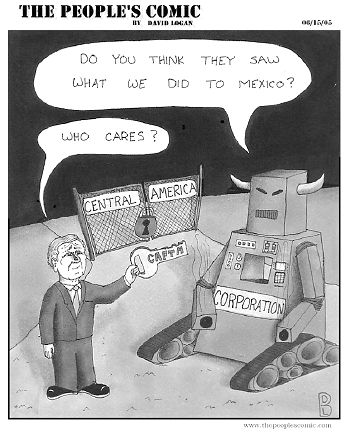

Mexicans Want Democracy, But Moreby David BaconOver a million people filled the streets along the historic route of Mexican social protest on May Day--marching from the Angel of Independence to the Zocalo, and then filling the enormous square at the city's center. This was the largest demonstration in the city's history, a great peaceful outpouring crying out, not just for formal democracy at the ballot box, but for more. The multitude demanded true choice in the country's coming national elections, but they wanted more than that too. People took to the streets to demand a basic change in their country's direction. Mexico has produced a unique political movement, uniting the population of the world's largest city, estimated at 21.5 million, with the 9.2 million Mexicans now living north of the border. And this exile population--so large that every person walking to the Zocalo now has at least one relative in the US--also wants change. Two sets of demands, voiced at the same time, posing the same basic questions, are becoming one. Last month, the country's President, Vicente Fox, attempted to impeach Mexico City Mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. Fox's attorney general, Rafael Macedo de la Concha, accused Lopez of using the city's power of eminent domain to take land for an access road to a new hospital, in defiance of a court order. The charge was a pretext, a political move to prevent him from running for president in 2006. The attempt backfired when growing public outcry instead forced the attorney general to resign three days before the march of the million. Lopez Obrador is undoubtedly Mexico's most popular politician. "He runs a boom government," explains Alejandro Alvarez, an economics professor at the National Autonomous University, "which promotes public works in the midst of economic paralysis. Despite the corruption scandal that ensnared his aides, he is basically honest. He criticizes the voracity of the banking system and Fox's free trade policies, he has an austere style in a country accustomed to the excesses of imperial presidents, and above all, he shows solidarity with the poor." Lopez' most popular acts so far have been to pay a small pension to all the city's aged residents, and provide school supplies to its children. As president, however, Lopez would hardly be a radical on the order of Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, who on May Day declared socialism his country's goal. This was also Mexico's official ideal of the 1930s and 40s, but a socialist direction is not the alternative Lopez Obrador has in mind. Alvarez notes that while he built a second deck on the main freeway circling the city for Mexico City's horrendous traffic, he capped the budget for the subway system, on which most poor residents depend. Lopez' program for redeveloping the historic city center is oriented towards business promotion, even to the extent of expelling the Mazahua indigenous street vendors there. "He adopted [former New York Mayor] Giuliani's 'zero tolerance' policy to improve personal security, but at the cost of violating individual rights, and shelved the investigation into the death of [indigenous rights attorney] Digna Ochoa in the face of grave inconsistencies in police procedure," Alvarez adds. Compromise or no, however, in the eyes of millions of Mexicans, Lopez Obrador represents a chance to scrap the present economic policies of Fox's National Action Party. Despite being lauded as the party that broke the 71-year stranglehold of the former ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), the PAN strategy of basing economic development on privatization and foreign investment is indistinguishable from the PRI before it. Both parties' austerity policies have held wages down and discouraged independent union organization, while opening Mexico to imports from the US. The flood of cheap corn--a staple crop of millions of small Mexican farmers--has multiplied by 15 times during the 12 years the North American Free Trade Agreement has been in effect. As a result, income has declined over the last two decades. The government itself estimates that 40 of the country's 104.5 million people live in poverty, 25 million in extreme poverty. Mexico has become an exporter both of the goods made by low-wage labor in foreign-owned border factories, and of labor itself, as millions of people cross that border looking for work in the north. The march of a million Mexicans is a clear demonstration that movements protesting those policies are growing. According to Alvarez, "the social movements of the last two years have been, in the countryside, openly against NAFTA, and in the city, against privatization and the dismantling of the welfare state." This is the upsurge in popular sentiment that Lopez Obrador hopes to ride into office, and the reason why he represents such a problem, not just for Fox, but for the Bush administration as well. Mexico, under the impetus of this movement, will go in the direction of Brazil, Ecuador, Argentina, Uruguay, and even Venezuela--rejecting the free trade model, and economic control from Washington. "What people want is justice," says Rufino Dominguez, coordinator of the Indigenous Front of Binational Organizations, a group that organizes indigenous people both in their home communities in Mexico, and as the latest and largest wave of migrants coming to the US. "To us, democracy means more than elections. It means economic stability--our capacity to make a living in Mexico, without having to migrate. It means a halt to the continued violation of human rights in our communities. It means having a government that attends to the needs of the people. We're tired of governments which put other interests first."

No one understands the price of free trade policies better than those who have paid it, leaving their homes and traveling thousands of miles in search of work. "We know the reasons we have to leave," Dominguez asserts. "Over 5000 of us have died trying to cross the border in the last decade." The Frente's leader in the southern Mexico state of Oaxaca, Juan Romualdo Gutierrez Cortez, an elementary school teacher, emphasizes that "migration is a necessity, not a choice -- there is no work here. Education is linked to development. You can't tell a child to study to be a doctor if there is no work for doctors in Mexico. It is a very daunting task for a Mexican teacher to convince students to get an education and stay in the country. Children learn by example. If a student sees his older brother migrate to the United States, build a house and buy a car, he will follow." Integrating Mexico's exile population into the country's political process is a fundamental part of its movement for democracy. Those pushed out by these economic forces want the right to participate in deciding whether or not free trade policies, responsible for their forced migration, should be changed. According to Jesus Martinez, a professor at California State University in Fresno, "Mexico has undergone a process of democratic transformation since the 1980s, but it is still incomplete. Mexicans living abroad, who represent 16% of the electorate, still have not been granted the right to vote. That's part of the inclusion that has to take place." Mexico's exile population is excluded from the political process that governs peoples' lives in the US as well. Undocumented migrants (estimated at over 4 million people) are excluded from all US social benefit programs. The US Congress recently decided to make obtaining a drivers license almost impossible. Even the act of working is a Federal crime, despite the fact that big sections of the US economy are totally dependent on migrant labor. Legal or not, Mexican migrants cannot vote to chose the political representatives who decide basic questions of wages and conditions at work, the education of their children, their healthcare or lack of it, or even whether they can walk the streets without fear of arrest and deportation. Although excluded from the US electorate, popular pressure to guarantee migrants the right to vote in Mexican elections has been growing for two decades. Last year, Martinez was elected a deputy to the Michoacan state legislature, representing his state's residents living abroad. He was a candidate of the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), the party of Lopez Obrador. "In Michoacan, we're trying to carry out reforms that can do justice to the role migrants play in our lives," Martinez says. "We have the most pro-immigrant governor in the state's history, who has finally treated migrant concerns as a priority." On a national level, however, the PAN and PRI have resisted change, while simultaneously claiming interest in the vote of Mexicans living abroad. Fox and the PAN congratulate migrants for sending home remittances to their families, which last year totaled $17 billion. This money now sustains entire communities, easing pressure on the government to find funding for education, healthcare, social services or economic development. Employers in the US likewise find the present system convenient, since they have no obligation to pay the cost of maintaining the communities from which their workers come. But convenience comes at a price. The Mexico-based political machines which produced the votes which kept the PRI in power for decades, and which now support the PAN as well, have little influence or control over the votes of people living thousands of miles away, in another country entirely. And Mexicans living in the US have little reason to be loyal to a political class that created the conditions forcing them to emigrate. PRI and PAN control the national congress, and while they voted over a decade ago to permit Mexicans in the US to vote, they only set up a system to implement that decision at the end of April. It is a very limited implementation. Voters will require a credential that can only be obtained in their home communities, and will only be able to vote by mail in 2006. Some observers believe that of the 9.2 million Mexicans living in the US, fewer than half a million will actually cast ballots. "It is limited," concedes Dominguez, "but it is the fruit of many years of fighting by organizations here in the US. It's not all we wanted, but it's a beginning. And most important, now that they've passed the law and started to create a process, there's no going back." Dominguez believes that in a close election, barring fraud, even the votes of 500,000 people could determine Mexico's next president. This prospect is as frightening to both PRI and PAN as the candidacy of Lopez Obrador. Not only might there be a candidate proposing a change in Mexico's direction, but a sizable number of people with good reasons for voting for him.

|

|