|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | ||||

|

||||

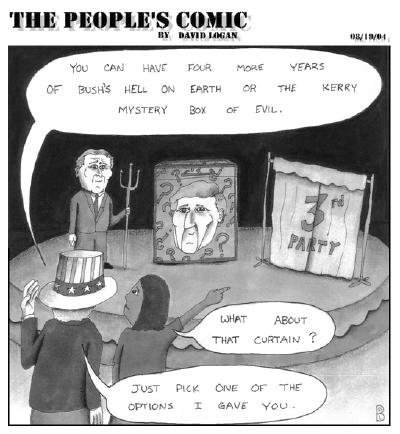

How to Handle Naderby Steven Hill and Rob RichieIn 2000, Al Gore beat George W. Bush in the state of New Mexico by a mere 356 votes--a slimmer margin than in Florida. Ralph Nader polled 21,000 votes. Nader not only nearly cost Gore the state, but forced him to expend valuable resources there in the campaign's waning days, draining his effort from Florida. Flash forward to 2004. Once again the Democratic and Republican candidates are locked in a tight race nationally. Once again Nader's entry into the race threatens Kerry's hold on New Mexico. And once again two candidates who share many views and bases of support--and who ideally could work together to challenge George Bush on the economy, the war in Iraq, the future of social security, the environment, political reform and health care--instead are players in a Cain and Abel drama, courtesy of the all-or-nothing, winner-take-all nature of our presidential election method. Yet there is a way out--if New Mexico Democrats decide they want one. Democrats control New Mexico's state legislature, and one of Kerry's leading vice-presidential contenders, Bill Richardson, is governor. Democrats could pass into law--right now--a runoff or instant runoff system with a majority requirement for president to ensure that the center-left does not split its vote between Kerry and Nader. Here's how. The Constitution mandates the antiquated Electoral College system for electing the president, in which there is a series of elections in the fifty states and the District of Columbia rather than one national election. But the Constitution specifically delegates to states the method of choosing its electors. States historically have used a variety of different approaches, including letting the state legislature appoint electors, as threatened by Florida Republicans in 2000. Nebraska and Maine, for example, award two electoral votes to the winner of the statewide vote and one vote to the winner of the popular vote in each congressional district (a flawed approach that would boost Republicans if in place nationally). The remaining states use a statewide winner-take-all plurality method where the highest vote-getter wins 100 percent of that state's electoral votes, even if that candidate wins less than a popular majority. With plurality voting, a majority of voters can split their vote among two or more candidates and end up winning nothing. Indeed because of the presence of Nader and other candidates like Pat Buchanan, nine states in 2000 awarded all their electoral votes to a candidate who did not win a popular majority. Fully 49 of 50 states were won without a majority in 1992. It is the lack of a majority requirement that leads Nader and Kerry forces to clash so bitterly. To be sure, Republicans may cry foul if New Mexico Democrats suddenly switch to a runoff system, but even if Democrats' action is self-interested, it's also in the public interest to protect majority rule and allow for voter choice. One approach would be to adopt a runoff system similar to that used in most presidential elections around the world, most southern primaries and many local elections: A first round with all candidates would take place in New Mexico in early October. The top two finishers would face off in November, with the winner certain to have a majority.

Better still would be to adopt instant runoff voting (IRV). Used in Ireland and Australia and recently adopted for city elections in San Francisco and for congressional and gubernatorial nominations by the Utah Republican Party, IRV has drawn support from Howard Dean, Jesse Jackson Jr. and John McCain. By allowing voters to rank the candidates (for example, a 1 for Ralph Nader and a 2 for John Kerry), IRV can resolve the spoiler problem. Voters are liberated to vote for their favorite candidate without helping to elect their least favorite. IRV also saves candidates the campaign costs of a runoff election and preserves more voter choice in the decisive November election when voter turnout is highest. New Mexico's state senate in fact already passed IRV legislation in 1999 in the wake of Democrats losing two congressional seats due in part to Green Party candidacies. Despite support from the AFL-CIO and Common Cause, the proposal died because of concerns about costs of implementing it and because some Democrats would rather destroy Greens than allow for co-existence. Democrats also call the shots in the presidential battleground states of Maine, West Virginia and Tennessee. With one vote of the legislature and a stroke of the governor's pen, these states could accommodate the reality of the Nader candidacy. The question is: what is stopping them? While Ralph Nader may be ready to risk a repeat of 2000--and could do much more to make multi-party democracy a viable option by highlighting reforms such as IRV--most Greens don't want to be spoilers. They consistently support reforming winner-take-all elections, and their presidential frontrunner David Cobb promises to focus this fall on safe states, in recognition of Greens' interest in defeating George Bush. But only Democrats and Republicans have the power to change the rules of the game. Democrats' failure to use that power begs the question: would they rather engage in name-calling and suppressing candidacies, even at the risk of costing themselves the presidential election, than allow new political voices to join the fray? More people, Democrats and non-Democrats alike, should begin asking party leaders: why not IRV? Steven Hill is a senior policy analyst with the Center for Voting and Democracy and author of "Fixing Elections: The Failure of America's Winner Take All Politics." Rob Richie is the Center's executive director. Contact the Center at www.fairvote.org . |

|