Seattle's Downtown Boom

The price of corporate welfare in Seattle

by John V. Fox

Free Press Contributor

Since the late 1970s, whole blocks of low income housing in downtown were wiped out to make way for over 15 million square feet of office space. Still more housing was removed for expensive hotel development, major retail complexes, lavish restaurants, and a convention center. Of course we were told that this facelift has more than paid for itself, returning jobs and taxes to the area's economy, and that ultimately, the benefits would trickle down to all of us.

There is, however, another way of looking at what's happened to our downtown, beginning with an examination of the costs of downtown growth and, more importantly, a look at who were the winners and losers. What you find is a legacy of at least 20 years of corporate welfare which has coincided with dramatically increasing levels of poverty, unemployment, and homelessness in the inner-city. Local government's role - far from helping us alleviate these conditions - actually has created them.

Over the decade of the 80s, hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars were committed for infrastructure and the support services needed for downtown expansion - police, sewer, fire, water, streets, electricity, and other utilities - at an annual cost of about one-third of the city's budget.

On top of that, there were several big ticket items - major capital improvements to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars - such as the $400 million bus tunnel. Transit planners said that a bus-only mall down Third Avenue at a cost of less than $50 million would have provided enough capacity through the 90s, but the corporate establishment insisted on a more expensive and higher capacity system that to this day remains underutilized. A new downtown electrical substation and expanded generating capacity also was required which contributed to significant increases in our utility bills over this period.

Marty Curry, director of the Seattle Planning Commission, which assists in development of the city's new land use plan, takes issue with the notion that there is too much focus on downtown: "A lot of public resources have gone to both downtown and the rest of the city. We just completed five recreation centers around the city." She also highlights the city's Neighborhood Matching Funds that free up dollars for neighborhood projects like p-patches, provided that the neighborhoods can match those dollars with "sweat equity."

I wonder if the Nordstrom family, downtown developers, or pro sports team owners were required to pitch in with their own sweat equity before they received the benefits of our tax dollars. The reality is that the public money spent to meet basic needs in our neighborhoods pales by comparison to what we have spent on downtown. The disparity is especially mind boggling in the face of growing poverty, more homelessness in our community, and deteriorating neighborhood streets.

The Gilded Eighties

The Convention Center, spanning the freeway at 8th and Pike, also was built at a public cost of over $150 million-$50 million over the projected cost. Even though modest improvements to the Seattle Center at a fraction of the price would have ensured an ample supply of convention and trade show space, the corporate establishment insisted on construction of a shiny new facility downtown. City planner Curry admits, "It partly relates to...lobbying. Probably the retail core businesses were very supportive of downtown placement of the Convention Center."

Large downtown property owners have an interest in positioning the Convention Center nearby, where it will attract additional hotel business, another large slew of shoppers, and, of course, drive up property values. Once it was built, Convention Center authorities called on the city council for special zoning exemptions, use of city street right of way, and $2 million from the general fund for roof supports so a garden park could be built on the Center's roof.

During the 80s, the city spent about $25 million to underwrite the cost of "improvements" at the Westlake Mall. In reality, this meant handing over a large chunk of dollars to one of the nation's wealthiest development corporations, the Rouse Company, so they could build a glitzy shopping complex which now covers the entire northside of the Mall. As a result, a 20-year citizen effort to create a large public green space was sacrificed and dozens of longtime small businesses were displaced. The city and the Port of Seattle during this period also spent over $30 million for tourist-oriented improvements along the central waterfront. In effect, the last of the upland warehouses, and most of the remaining piers (that used to provide a host of working class jobs) were "upgraded" and turned into offices and trendy shops. A new art museum was also built during this period in downtown at a public cost of over $50 million.

Of course we were told that this would make Seattle a "world class city", and that "what's good for downtown is good for the rest of us." Far from it. In the mid-80s, the City contracted with Gruen and Gruen Associates, a large San Francisco based accounting firm, to complete a cost/benefit analysis of expected downtown growth. That study showed that the cost of maintaining and adding public services and infrastructure to downtown would greatly exceed any tax revenues realized by the boom. The results were buried in a larger city document that never saw the light of day. And while downtown growth during the 80s did generate employment, few of these jobs went to blue collar workers - a group that still makes up a large portion of Seattle's workforce. According to State Employment Security data, blue collar employment today is twice that of the white collar sector. People of color have also been left out. In the Southend and Central area, unemployment remains two to three times that of whites with the rate rising to 50 percent if you are young and black.

|

|

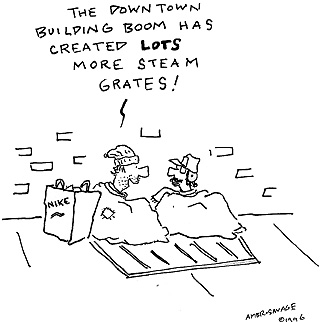

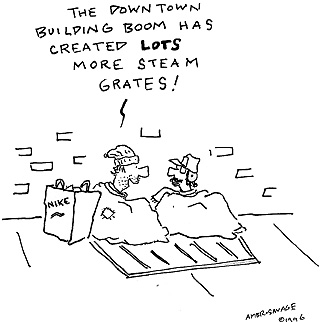

John Ambrosavage © 1996

|

Perhaps the most devastating by-product of downtown growth has been the dramatic loss of low income housing. According to city figures, over 4000 units have been lost since 1980 just in downtown. And, city wide, the increased demand for housing created by the influx of new office workers has driven up rents in all our neighborhoods. The average price of a home jumped from about $45,000 in 1977 to over $160,000 today. City-wide over 4000 low cost units have been lost just to demolition since 1987. Thousands of additional units have been lost to abandonment, conversion, and high rents. According to city census data, almost half of the city's renters - who now make up the majority of Seattle's households - now are paying close to 50 percent of their income on rent.

City planning director Curry professes frustration about obtaining funding for low income housing and programs which help the homeless. Such programs require ongoing social services. "Social service dollars are harder to get than capital project dollars, because capital projects are tangible. This is true whether it's private funding or federal funding."

But the downtown growth that brought us many of these changes was not simply a result of the inexorable motions of the marketplace, the whims of funding, or other forces we could not control. On the contrary, what happened was a conscious by-product of public policy decisions made by our mayor and city council. That's why on any given day in Seattle, there are over 3000 to 5000 homeless people on our streets, according to city shelter data. That's why we have little or no resources to provide jobs for people of color in the central area and southend and to meet other needs in our neighborhoods. Our elected officials have made a conscious decision to promote the downtown boom at the expense of our communities. As a consequence, we are a community that is increasingly divided by income, race, and class and increasingly separated culturally, spatially, and psychologically.

That's Not All, Folks

Given the enormous levels of public subsidy invested in downtown during the '80s at a time when neighborhoods could not even get a pothole filled, it was especially galling when in the early 90s, corporate leaders and the mayor informed us that downtown had been "neglected." Of course the newspapers helped spread the myth - to justify another round of even larger multi-million dollar contributions for downtown. Take a look at the public cost of downtown projects underway or built since 1990:

- $40 million for a Concert Hall in downtown. The Krellsheimer Foundation years ago had set aside land for this project at the Seattle Center where it could have been built at much less cost to taxpayers, but the downtown establishment insisted on a downtown location. The project will go up on a block where low income housing once stood. According to a November 1994 Seattle Times article, councilmember Tom Weeks (who just this Fall vacated his seat), acknowledged that the city council was forced to cut the 1995-96 budget by $15 million, sacrificing funds for basic city services to accommodate this facility.

- $360 million for a new baseball stadium - a cost that now is 50 million dollars over its original price tag. It's also interesting to note that where the Kingdome has offered about 45,000 low-cost general admission seats to baseball fans, the new ballfield will have only a few thousand, preferencing the more expensive seats and luxury boxes.

- $90 million in public funds to the Nordstroms to assist them in their move to the old Frederick & Nelson building. Mayor Rice, committing the time of dozens of city staffers, worked tirelessly to assist the Nordstrom company and related developers in securing city council approval for use of city funds to construct a parking garage. Council approval also was obtained for a sky bridge linking the garage to the new Nordstrom building. (See related stories, "Nordstrom Deal Update" and "Rice Subject of HUD Investigation").

- $115 million in city funds were allocated to buy the Gateway Tower for a new City Hall. Given that the building has had only about a 50 percent occupancy rate since it was built in the mid-80s, and that it was largely owned by Herman Sarkowsky, one of the city's most influential downtown developers, a longtime patron of the arts, and friend of several councilmembers, critics of this deal have called it nothing more than a corporate bailout.

- $200 million for expansion of the State Convention Center. We were told only 10 years ago that the existing facility had 30 years of adequate capacity and would pay for itself. It's been operating in the red since it was built. The city handed over $10 million to accommodate this expansion, including revenues from the Freeway Parking Garage - originally built in part with Block Grant Funds earmarked to serve low income people. The expansion will also wipe out another 150 units of low income housing and cost the state and city about $10 million to replace these units.

Sticker Shock

Imagine adding the $400 million Seattle Commons onto this total. No wonder Seattle voters balked when they were asked to support this project. Indeed, sticker shock has begun to set in among Seattle voters. There is no question that is why Charlie Chong was recently elected to the City Council. Chong, very much of a populist, clearly distinguished himself as the neighborhood candidate. He was able to soundly defeat Bob Rohan by highlighting Rohan's downtown connections and his corporate liberal background. It is refreshing to once again find ourselves with at least one councilmember who, when asked how he will review future downtown projects, says "our quality of life has gone downhill as a result of downtown revitalization. There is a direct correlation."

Other councilmembers may be taking notes. Gary Davis, who formerly worked on the Seattle Commons campaign and now is an assistant to councilmember Tina Podlodowski, asserts that "the city tended in past years to focus on the big catalysts: Nordstrom, the Nike store, I. Magnin. The new focus is what happens to the neighborhoods downtown." Podlodowski herself volunteered to chair the Neighborhood Planning Committee after taking office early in 1996.

Unlike the Commons issue, voters usually have not even been given a chance to vote on downtown projects. And it is this matter that is of particular concern to Charlie Chong. In reference to future big ticket items, Chong says "I will be asking questions in public and in private meetings. How will you pay for this? Who will benefit?" He is quick to highlight the fact that "the dollars the city used to finance revitalization downtown came from councilmanic bonds, not voter approved sources."

True Leadership Needed

We are at a crossroads in this city. If we accept the same old rhetoric - that the horses in downtown must be fed, in order to feed us sparrows - then we can expect not only more homelessness, unemployment, and poverty, but a real and perceptible shift in the quality of life in our city. We will have our highrises, our upscale hotels, and tourist attractions downtown, but the price will be a city that increasingly resembles the dystopic reality of Los Angeles, Detroit, or Washington D.C - divided, fortified, and gated - a city that sets policy and shapes its physical environment out of fear and the need to contain growing numbers of disenfranchised and alienated people. Seattle already has moved down this road, allocating more of its resources for social control rather than social services.

We now have a Weed and Seed program, a drug loitering law, no camping laws and nightime curfews in our parks to keep the homeless out, a pedestrian interference law, jail time for those caught drinking or urinating in public, a no postering law, aggressive use of trespass laws, a virtual ban on teen nightclubs, a no-sitting law, more police, and expanded use of private security. No wonder we are building a shiny new jail, not to protect the public from violent criminals, but to house all those people, especially the homeless, poor people, and people of color who have been criminalized as a result of these measures. Ironically, City Attorney Mark Sidran has called them "civility laws".

Few if any of the city's larger policies are measured first from the standpoint of how they affect the distribution of resources in our communities. We need to build a broad coalition of progressive forces in this city that would include disaffected neighborhoods, small independent businesses, communities of color, the poor, the homeless, and their advocates, young people, immigrants, as well as progressive elements within the labor movement.

The issue of downtown corporate welfare is the issue that could bring these groups together. Around such a rallying cry, there is a potential for a movement that could force the election of new leaders willing to cast aside the old assumptions and make a moral commitment to achieving equity and economic justice in our city - that's the stuff of true leadership. Until we get it, we are condemned merely to repeating the mistakes already made by other cities across this country.

Doug Collins contributed to the research of this story.

Please see related corporate welfare stories:

Managed Care: Less Care, More Profits

Nordstrom Deal Update

Corporate Welfare Resources on the 'Net

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the January/February, 1997 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1997 WFP Collective, Inc.