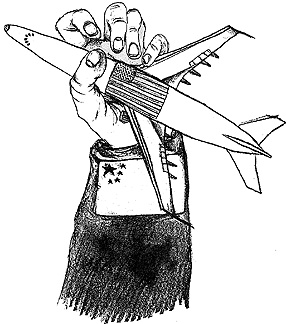

Boeing Jobs Take Flight for Profit

by Donald Barlett and James Steele

Excerpted with permission from America: Who Stole the Dream?

Illustration by Jeff Weedman

The way to encourage export sales, according to big business and Washington, is through "free trade." Every nation agrees to lower the tariffs that make imported products so expensive. Nations no longer protect their key industries by keeping out rival products made by foreign competitors. Industries are free to grow worldwide, limited only by the quality of what they produce.

But consider what has happened since 1979, the peak year for manufacturing employment. Since 1979, the United States has run up a merchandise trade deficit of $1.7 trillion - meaning Americans have bought that much more in foreign televisions, computers, clothing, autos and other products than we have sold abroad.

As is the case with so many U.S. government economic policies, on the issue of trade, there has been no middle ground. Other nations haven't taken such a radical position. They have kept some barriers to protect their workers and their most important industries. Thus, Germany limits imports of cars from Japan. Japan restricts imports of telecommunications equipment. France limits imports of food products.

From 1980 to 1995, the United States compiled a perfect record - 16 merchandise trade deficits in 16 years. It was the worst trade performance in the world. During that same period, Sweden posted trade surpluses in 13 of the 16 years. Its last deficit year was 1982. The Netherlands recorded trade surpluses in 14 years. Its last deficit year was 1980. Germany achieved trade surpluses in all 16 years, for an overall surplus of $625 billion. And Japan had trade surpluses in 16 consecutive years for an overall surplus of $1.1 trillion.

Because there is no middle ground on trade, U.S. policy makers have thrown open the American market even to those countries that have imposed take-it-or-leave it ultimatums on the government and on American business - ultimatums that, if agreed to, will cost the jobs of millions of American workers.

Take the case of the Boeing Co., the premier manufacturer of jet aircraft. Boeing ranks among the top dozen American companies in exports, and thus, if the claims about the benefits of export-driven jobs are accurate, should be providing good-paying jobs for Americans.

But look at what is happening to Boeing jobs. In January 1990, Boeing employed 155,900 people, largely at its home plant in Seattle and at facilities in Wichita, Kan., and in the Philadelphia area. Over the next six years, Boeing slashed one-third of its workforce, bringing the number of employees to 103, 600 in February 1996.

One reason for the shrinking workforce: airplane parts once made here by Boeing employees now are manufactured by subcontractors in other countries and shipped back to the United States for assembly. On a 747 jumbo jet, for example the nose gear, the landing gear, the outboard and inboard flaps and spoilers all contain parts made in Japan. At present, about 40 percent of the parts of a Boeing 777 are manufactured outside the United States. That number is expected to reach 50 percent over the next few years.

To sell planes in other countries, Boeing agreed to move a portion of its manufacturing to those countries, to provide employment for people there to make aircraft parts. That eliminated the jobs of U.S. workers.

Frank Schrontz, chairman of Boeing, explained this practice, albeit in a roundabout way, at a 1995 stockholders meeting. His comments came in response to a question about joint-production agreements with other countries.

Said Schrontz: "It is necessary, as we sell into the world market, for us to have an access to that market, and in many cases that requires that we ask the countries, and companies within those countries, to participate in that aircraft production. We are trying to put those activities out in which they can do a better job than we can and it does not destroy our core technologies, but some of that market access is simply going to have to be a trade for putting work outside."

To that end, Boeing buys the parts of the wings for its jumbo 747s and for its 737s from the Xian Aircraft Co., the Chinese company that built MIG fighter planes. China has imposed that requirement as a condition of the sale. Eventually, the Chinese factory will produce the tail section for the 737, which now is made at the Boeing plant in Wichita. Chinese engineers have visited Boeing facilities in the United States and Boeing engineers have visited China.

To that end, Boeing buys the parts of the wings for its jumbo 747s and for its 737s from the Xian Aircraft Co., the Chinese company that built MIG fighter planes. China has imposed that requirement as a condition of the sale. Eventually, the Chinese factory will produce the tail section for the 737, which now is made at the Boeing plant in Wichita. Chinese engineers have visited Boeing facilities in the United States and Boeing engineers have visited China.

How did the Chinese factory secure the tooling and machinery to build tail sections? Boeing supplied the tooling. When asked whether Boeing furnishes tooling to its subcontractors in the United States, a company representative replied: "Boeing provides tooling for some suppliers, and the some suppliers provide their own tooling, So it's both."

In addition to tooling, Boeing has provided flight and maintenance training, helped Chinese airlines establish safety departments, provided flight simulators and pilot training, and established a corporate office in China. The company also has opened what it describes as "one of the largest aircraft spare parts centers in the world," at Beijing's capital Airport. The center stocks more than 30,000 parts.

For their part, Boeing officials view all this as good news. At least for the Chinese. Larry Clarkson, senior vice president of planning and international development, told a conference in Singapore in early 1996 that Western trade with China is "helping millions of Chinese obtain greater freedom to chose their work, their employer, and their place of residence."

Now listen to another view, expressed by an American labor leader who has been an observer of the Boeing-China trade process close-up - both in the United States and China - and who is sympathetic to Boeing's "predicament": "China has all these five-year plans for autos, aerospace, etc. They are going to develop these industries. They are going to be the basis of the new China." Because it's such a big market, they say to Boeing or Airbus or whoever wants to sell in China: "We'll buy thirty 737s. We'll want to produce the back end of the 737 in China. You give us the machinery. You give us the engineers. You give us the technology. You help us set up the facility. And then we'll build the airplane...."

"It is the biggest foreign subcontracting order the Chinese have ever had. They see it as a blueprint for the development of their aerospace industry. You see a top Boeing executive saying, 'Boeing is committed to developing the Chinese aerospace industry...'"

The source, who has visited the Xian factory where the Chinese are making aircraft parts for the 737, went on: "There are more than 500,000 Chinese employed in the aerospace industry. The average wage rates are $50 a month. I saw Xian, which employs 20,000 workers who live in barracks. The government role is totally coordinated, totally subsidized."

In instructing China, step by step, on how to build its aircraft, Boeing is essentially setting a competitor up in business. The day may well come when China can supply to the world at least some of the planes that Boeing now does, and do it more cheaply. But like much of American business today - and most specifically those businesses that are publicly owned and susceptible to pressures from Wall Street - the Boeing-China deal was more for short-term gains, at the expense of any long-term commitment in America.

It was also made at the expense of the American taxpayers - on two counts. First, was the actual sale of the planes to China. From 1993 to 1995, the Export-Import Bank of the United States guaranteed loans totaling $1.4 billion for China's purchase of Boeing aircraft. That made China the Ex-Im Bank's largest customer in Asia.

The Ex-Im Bank is an independent agency of the U.S. government which, in its own words, "has one mission: to help the private sector create and maintain American jobs by financing exports."

Thus, a U.S. government agency backed by American taxpayers helped finance the sale of planes in China that will be built, in part, by workers in China. Or, if you will, U.S. government financing will create jobs in China.

Second, Boeing and the rest of the civilian aviation industry, perhaps more than any other industry, owe their technology leadership to the tens of billions of taxpayer dollars spent on research and development of military aircraft. Now some of Boeing's technology is being given away to the Chinese.

Boeing is not the first American corporation to follow this path. It is merely doing what the American electronics industry did many years ago: selling off the technology and manufacturing processes that made the companies and contributed to the overall health and wealth of the nation, its workers and communities.

Back in the 1960s, Japan blocked imports of American-made television sets and instead required U.S. companies to license their technology to Japanese manufacturers. That's one reason why foreign suppliers today control the American market for television sets - as well as a variety of other products, including radios, VCRs and portable computer display panels. And why no American companies manufacture television sets in the United States today.

More significant, Boeing's role in the global economy underscores why Washington's trade policies have been such a failure for the ordinary working American - and why the worst is yet to come: while Boeing cannot sell aircraft to China unless it builds part of its planes in that country, the United States does not impose any similar requirements on China or other countries.

The point is, American corporations hungry for sales routinely agree to all manner of conditions set by foreign governments - while Washington asks little or nothing from foreign producers wanting to crack this, the largest consumer market in the world. Call it one-way trade, but it's not fair trade. And the numbers show it.

Ten years ago, in 1986, China exported $4.7 billion worth of goods to the United States. In 1995, imports from China totaled $45.5 billion. U.S. exports trailed far behind. So the U.S. trade deficit with China jumped from $1.6 billion in 1986 to $33.8 billion in 1995 - an increase of 2,012 percent. That's a huge number. You might want to think of it this way: if personal finances had gone up at the same rate, the average American family in 1996 would earn more than $600,000.

In any case, if the deficit trend continues, China will replace Japan as the United State's most unequal trading partner shortly after the turn of the century. The United States then will have massive, structural trade deficits with two countries, instead of one.

Donald Barlett and James Steele are veteran reporters with the Philadelphia Inquirer. Their 1992 series of articles, America: What Went Wrong?, which examined the abandonment of American workers, won a Pulitzer prize. This year's series of articles, America: Who Stole the Dream?, will appear in bookstores soon.

Please see a reader response to this article:

"Workers Are Without a Voice" (WFP Issue 27 May/June 1997)

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the November/December, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.

To that end, Boeing buys the parts of the wings for its jumbo 747s and for its 737s from the Xian Aircraft Co., the Chinese company that built MIG fighter planes. China has imposed that requirement as a condition of the sale. Eventually, the Chinese factory will produce the tail section for the 737, which now is made at the Boeing plant in Wichita. Chinese engineers have visited Boeing facilities in the United States and Boeing engineers have visited China.

To that end, Boeing buys the parts of the wings for its jumbo 747s and for its 737s from the Xian Aircraft Co., the Chinese company that built MIG fighter planes. China has imposed that requirement as a condition of the sale. Eventually, the Chinese factory will produce the tail section for the 737, which now is made at the Boeing plant in Wichita. Chinese engineers have visited Boeing facilities in the United States and Boeing engineers have visited China.