|

||||

|

|

|

|||

| Home | Subscribe | Back Issues | The Organization | Volunteer | Do Something | ||||

|

||||

|

The Benefits of Being Near by Doug Collins

As Americans born in the 20th Century, we've been raised in a culture of expanding bigness, with speedy long-distance travel to get us between far-flung locations. According to the US Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the average American in 1900 traveled less than 2,000 miles per year, nearly all of which was within 50 miles of home. About 100 years later, the average American traveled close to 18,000 miles per year, nearly half of which was more than 50 miles from home. Part of this 20th-Century ethos is that we automatically assume that long-distance travel is good. It's what people do on vacations. It's exotic and fun. Regarding work commute, high-speed travel by car enables many Americans to fulfill their dreams of buying cheaper, bigger houses in quiet suburban areas, dozens of miles from work. I'm actually afraid that we Americans--in so doing--have forgotten the goodness of having people and things close at hand, of not traveling too much, of avoiding the commute. I'd like to explore a bit the benefits of being near.

Buying Near It's very tempting to buy exotic, imported goods, but I can think of a lot of advantages to buying goods produced locally. When you buy locally, from local producers, your dollars stay in the region and circulate here, rather than being sucked away by a giant multinational corporation, to be spent at some posh executive retreat on a Pacific island resort. The huge national trade deficit is alleviated when you buy domestic rather than imported goods. Many economists think that could help prevent a future crash of our currency. Furthermore, imports from far away--usually China--are likely to be produced with lower labor standards than goods produced in this country (though I should be careful to say that our own labor standards are nothing to brag about). There are climate benefits as well. The energy used to transport goods overseas likely creates much more carbon emissions than the transportation of domestic products. In a lot of ways, sourcing goods from closer-by is just a heck of a lot more efficient and direct. Because they have long understood the value of small spaces, the Japanese invented the much-touted and super-efficient "just-in-time" manufacturing process, which stresses the importance of having parts inventory very close at hand.

Closer Home Life Living closer as a family, in a more compact home, has emotional, financial, and environmental advantages. Large houses require a lot of energy to heat, cool, and light. Much of our energy is carbon based, so this makes climate change worse, not to mention the costs of your utility bills. When you live in a large house, you also feel that you have to fill each room with furniture and other accessories, so the costs snowball. Smaller homes are much more efficient to maintain, and the land and structure are smaller and cheaper, too. In fact, living in a smaller space can cut costs tremendously for a family, as well as for an individual living alone. That's certainly not a bad idea for the many debt-ridden people among us. On an emotional level, if kids all have their own separate rooms, then parents generally will have less knowledge of what kids are doing or thinking. When family members share rooms, they share experiences, and--I would guess--will generally be closer emotionally. Though it is true that many Americans would experience some rough times transitioning toward such closeness, that's only because they are now accustomed to distance and space, and the easy escape of their private rooms. Regarding the concept of space in the US, as a parent of toddlers, I recently received a booklet entitled "Winning Ways To Talk With Young Children" from the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services. In the booklet, I read the following dialog quiz for parents:

"Melissa says, 'Mommy, I'm scared to sleep alone.' Which response communicates acceptance? A: You ought to be ashamed! You're acting like a big baby! You know there's nothing to be scared of! B: I know you're frightened. I'll turn on the light and leave the door open for you. (Example B indicates acceptance)"

When I read this, I felt sad. The "correct" response seemed cold. What did little Melissa really need? Acceptance, or closeness? Even our public health officials apparently have no understanding of the loneliness and distance that many American kids feel in their solo bedrooms. But American kids feel it all the time. That is, until they also get accustomed to escaping to private rooms in large houses, often wrapped up in a video-game replacement for human contact, or internet chat-rooms with people who at least pay some attention to them.

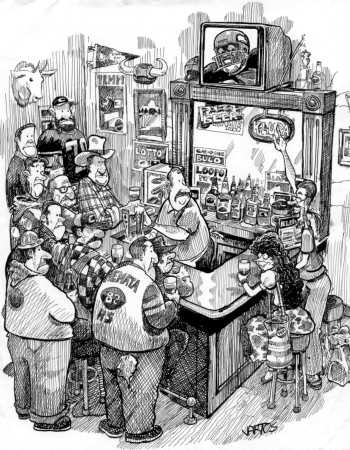

Enjoying the world at hand People from industrialized countries nowadays take jet vacations and meet the indigenous people of Bali, but they might not ever walk to their neighbor's porchstep. Our lives would be very different if we spent our free days tooling around our neighborhood rather than trekking in Katmandhu or Eurrailing. With closer connections to our neighbors, our neighborhoods would be more crime-resistant. We would understand local issues and problems better, and hear the perspectives of other locals. Do you want exotic? Try the living room of any of your neighbors. It's probably much different from your own. Most cities have ethnic neighborhoods or special enclaves. Go to a biker bar. Eat at the Mexican restaurant that the Mexicans go to. If you're a white American, go to Chinatown or the African-American neighborhood. Visit these if you want exotic. In most cases, exotic is right at hand, and you don't even realize it. You don't need to buy a plane ticket to get to it, nor any carbon offsets to atone for environmental guilt. You probably just need your feet. I don't mean to say that far-off travel is without merit. Certainly it can be very interesting and fun. But most people who travel internationally just go for a few days, maybe a couple weeks maximum. We don't gain much real perspective on our whirlwind tours. "If this is Tuesday, it must be Belgium." If we travel to a far-off land, isn't it better to have an excuse to stay a year or two, long enough to start identifying with the culture we're visiting, rather than just coming and going with little insight? Another urge that many of us Americans sometimes get is to travel to a far-off location to help others in need, in disadvantaged or disaster-stricken areas. This sort of travel is laudable, but is not immune to questionable motivations. If you travel in this way, are you doing it out of love for humanity, or as a means of bringing your "superior" ways, knowledge, or products to another land. Assuming that other cultures need and want our ways is one of the most laughable--and sad--mistakes that many Americans make. It's the same mistake that has led us into two huge, disastrous, and unwinnable wars in the past half century, when instead we should have just stayed nearby at home. An old Chinese Taoist proverb says, "The farther you go, the less you know." I like this proverb a lot, partly for its variety of interpretations. We Americans tend to think that long-distance travel can be a valuable learning experience. Certainly we can learn intriguing ideas from other lands, but what good are these intellectual notions if they are not even recognized back home, here in the United States? If a person tries to import intriguing foreign practices and ideas here, most other people will--for better or worse--just think he or she is odd. Positive change is something that is negotiated in the discussion, consideration, and feeling of many people who find themselves together, rather than through an imposition of new ideas from outside. Ultimately, as many Buddhists might point out, the answers lies closer at hand: in ourselves, or at least nearby.*

|

|