Don't Shop When You're Hungry

by Fredrika Sprengle

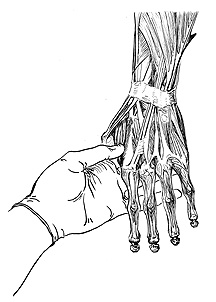

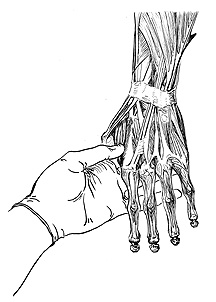

illustration by Kathleen Skeels

Free Press Contributors

When people in your own family die, it is nothing like in the movies. It is usually exhaustion, rather than drama, that is felt. The flailing about is limited and tiresome, as are the bedside revelations, and sweet insights. As my ninety-eight year old Uncle Fred died he hallucinated for hours at a time. It was not peaceful or enlightening; he was afraid and often in pain. Once, I took his hand in mine, and he became ashamed and worried, calling me by the name of a long ago youthful flirtation. "Won't somebody see?" he said, sheepishly.

After my mother died they couldn't make the narrow inside corner of the mobile home with her stiff body. They had to take out a window, and hoist her through it-something she would have found both humiliating and horribly funny. In fact, if it had happened to someone else, I can hear her from her spot on the couch, laughing so hard as she told her irreverent story, that she would be unable to finish the gruesome ending: that they "hauled her ass out through the fucking bedroom window with a block and tackle."

Probably worse than haunting death scenes, though, is the impersonal truth of doing this grueling personal event with business and service people who invoke the furrowed brows of deep sincerity. My mother's second husband arranged for a memorial service despite her not caring for such things. I figured he did that on impulse, to appease his own large Catholic family, which was basically okay with me. So there, at a Catholic church in the woods, was a memorial service for my mom. The man who ran the service had never met my mom, but spoke on and on about what kind of a woman she was.

He preached with enthusiasm, calling her name over and over, about her personal relationship with Jesus, and how there was nothing she liked better than a good sermon. I cried and almost laughed out loud, because my mother was an agnostic, who from the time I was a child spoke with disdain for church. She used her sharp and sometimes merciless tongue to make fun of the pill-hat wearing, sanctimonious church ladies. I can only imagine how this commendation was created between my mom's recent husband and the preacher. I wonder what kind of donation was requested. The world that is built around death is fertile ground for absurdity. It grows like mildew in a damp basement.

He preached with enthusiasm, calling her name over and over, about her personal relationship with Jesus, and how there was nothing she liked better than a good sermon. I cried and almost laughed out loud, because my mother was an agnostic, who from the time I was a child spoke with disdain for church. She used her sharp and sometimes merciless tongue to make fun of the pill-hat wearing, sanctimonious church ladies. I can only imagine how this commendation was created between my mom's recent husband and the preacher. I wonder what kind of donation was requested. The world that is built around death is fertile ground for absurdity. It grows like mildew in a damp basement.

Because the memorial service was postponed at the last minute, my sister had to leave and she sent what must have been a very expensive flower arrangement. The delphiniums and iris, which were mom's favorites, were a nice touch. To this day I haven't had the heart to tell her that it was draped with a tacky blue banner that said MOTHER in serpentine gold script on it.

But, the most unnerving part of death, for a person like me who likes to deliberate about decisions, is the urgency with which all the experts push you to move. It's promoted with the intensity, care, and thoughtfulness of the Bon's One Day Sale. "You have only twelve hours", "We have to leave now","The body must be there by the morning." What about the funeral, the mortuary, the insurance company, the newspapers? Everything, even the obituaries, cost. It's like writing a morbid personals ad. So much money for each line. Each quality you want to name costs a buck. Each relative's name listed another buck, or two. Still stunned with the image of my mom being heaved through a bedroom window, I wanted to sit down in front of her woodstove and wait until the image weakened.

There is confusion and cost around each corner of death. My parents thought that funerals were barbaric, and while they talked openly about death, they wouldn't allow any talk of funerals. My father had willed his body to the University of Washington, which we all thought seemed sensible. It would be easy and humane. Besides, it was free. We didn't know, until his death, (decades after his decision), that the there were conditions that the University had for accepting his body. For instance, they wouldn't accept it if it had been autopsied, or if he died of the wrong things. There was lots of confusion and angst about who would pay for the substantial transportation fee from the morgue, in an outlying area, to the college.

It's crazy all these things that need to be paid for. Who can think of it all, especially in a culture that doesn't discuss death. It's all hurry, hurry, hurry, or something terrible will happen: the body will rot on the way to the morgue, the ashes will be lost, he will be buried in an unmarked grave.

Death is messy. The last days can be troublesome; the realization following the event is a singular experience. There is nothing crueler at those moments than to be hit with a barrage of ridiculous decisions, making transactions with people who have forgotten that although they do this stuff day in and day out, most of us will only have the first-hand experience of handling the business of someone's death a few times, maybe only once, in our lives. We've heard or witnessed the stories: the shock about the waxy pink make-up on a husband's face when he was laid out; Wives who are told that he should be wearing a suit, when he wore jeans all his life, so someone must shop.

Years ago, my friend, an only son, knew his mother was dying and the two of them talked about her impending death. He stayed with her for the last month of her life. He built the casket himself. And when she died, he washed his mom, dressed her in clothes she had chosen, and placed her in the coffin.

When I first heard of all this proximity to death, it sounded morbid. But thinking back to his face as he told the story, I now understand the sanity of their way. That he spent time alone with his mother's body began to sound less shocking and more honest.

When bodies are whisked away, pumped full of chemicals, dressed up in unfamiliar ways, and given a face that is not their own, that is barbaric. We don't have a chance to grasp the magnitude of what is happening-to learn about death directly.

Next time I deal with death, I hope I can do it differently. I don't want to try to make it disappear, or have it made into a costly and sanitary exhibition.

I suppose the best we can do is to be as careful with the decisions about death as those about health care or food. Beware, be informed, do-it-yourself, and don't shop when you're grieving or hungry.

Related Articles:

Beat the Devil

You Can't Take it With You...

D.I.Y. - R.I.P.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents this page were published in the March/April, 1998 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1998 WFP Collective, Inc.

He preached with enthusiasm, calling her name over and over, about her personal relationship with Jesus, and how there was nothing she liked better than a good sermon. I cried and almost laughed out loud, because my mother was an agnostic, who from the time I was a child spoke with disdain for church. She used her sharp and sometimes merciless tongue to make fun of the pill-hat wearing, sanctimonious church ladies. I can only imagine how this commendation was created between my mom's recent husband and the preacher. I wonder what kind of donation was requested. The world that is built around death is fertile ground for absurdity. It grows like mildew in a damp basement.

He preached with enthusiasm, calling her name over and over, about her personal relationship with Jesus, and how there was nothing she liked better than a good sermon. I cried and almost laughed out loud, because my mother was an agnostic, who from the time I was a child spoke with disdain for church. She used her sharp and sometimes merciless tongue to make fun of the pill-hat wearing, sanctimonious church ladies. I can only imagine how this commendation was created between my mom's recent husband and the preacher. I wonder what kind of donation was requested. The world that is built around death is fertile ground for absurdity. It grows like mildew in a damp basement.