|

|

|

|

|

Contents this page were published in the May/June, 1997 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1997 WFP Collective, Inc.

REGIONAL WRITERS

IN REVIEW

|

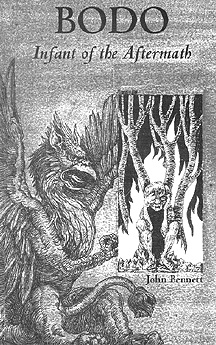

by John Bennett The Smith, 1995 185 pages, $14.95 paperback |

What's most interesting about this tragic novel is that Bennett has chosen to tell the story of the aftermath of war and not just of the horror itself. Gźnter Grass in Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum) , Jerzy Kosinski in The Painted Bird, and Elie Wiesel in La Nuit (Night) , had already graphically explored the horror of World War II through the experience of particular European boys. What Bennett decided to do, instead, was to recount the hope and failure of a German war orphan's adulthood. Bodo: Infant of the Aftermath is a tale of how one young man bore his psychological scarring and became not a monster but a Nietzschean hero-a traumatized innocent trying to balance his pain, a crazy D.J. prophet proclaiming new values to a society deaf to his wild truth.

"Bodo" was the name the orphanage nurse gave to the five-year-old boy. It was the closest German name to the nickname "Bud," which his first rescuer, a Fagin-like American sergeant who ran a black-market club for boys, had used when Bodo couldn't tell them his given name. Bodo had been driven into repressed silence one night at the end of the war when victorious Russian soldiers rampaged through his family's farm house. Bodo had fought back for the sake of his twin sister, his mother, and grandmother; the soldiers in turn brutally tortured him.

Bodo is adopted by an American Army radio engineer, Walter Steiner, and Walter's German bride, Alma. Growing up in their Beaumont, Texas home, Bodo gravitates to positive attitudes in response to his psychological pain -- he becomes a perfectly behaved boy, riding a "wave of nervous energy that never seemed to wane." Alma is never a mother to him, but more his opposite, a negative, shadow self of bitterness and judgment. For Alma is a victim too, not so much of the war as of the repeated rapes she had suffered as a child. "She had been driven so far into herself or so far out that her body had become a thing with neutered emotions."

|

"Bennett has written movingly of pain, of dreams that slowly suffocate, and of realities that strike you like a cane." |

Bodo finds his passion in his father's work. Walter is interested only in the functional details of making radios work; Bodo, however, is drawn to its power. He is fascinated by the D.J. behind the soundproof glass in "a constant state of agitation. His mouth went all the time and surprise, consternation, and sincerity registered in rapid succession on his face. He coaxed and cajoled a massive, invisible audience." And the D.J. at Walter's station lets Bodo cue up records and sit in for him, until the day Bodo introduces Jerry Lee Lewis as "settin' his balls on fire!" Something Bodo didn't understand had forced those words out of his mouth.

After high school Bodo escapes the intensity of first love by moving to New Orleans, a city Bennett captures in clear-eyed, realistic detail. Bodo lands a D.J. job and wins critical notoriety for the intensity of his hip patter. But Walter dies and the Vietnam War intensifies and Bodo is pulled into the vortex of past and present violence. He starts to rock and sweat and preach on-air about American culture: how the first talkie movie wasn't by Al Jolson but starred black piano player Eubie Blake; how Colonel George Patton boasted, "I do like to see the arms and legs fly!" And he's thrown off another radio station.

Out on the coast, Bodo tries to keep his nightmares at bay with amphetamines and his despair in check with a new vision ripe for San Francisco: "Sun, Fun and Kids," he announces to erstwhile friends, gurus, and psychiatrists. But the time for innocence is over and all anyone sees is Bodo's madness.

Throughout the novel, Bennett wily uses smiles as a motif to indicate psychological states. Some of the most terrifying feelings are accompanied by chilling smiles. When Walter and Alma first meet Bodo, he smiles a frightening smile "his eyes intense and the muscles in his face quivering." At Walter's burial, "Bodo mirrored Alma's bitter smile...."

In Bodo: Infant of the Aftermath, Bennett has written movingly of pain, of dreams that slowly suffocate, and of realities that strike you like a cane swung against the bridge of your nose. His story captures authentic lives. But structurally the novel's linkages are weak. The shifts in point of view are interesting but do not flow well. The book is not smoothly, crafted; it reads as if it has been wrenched out and birthed. Bennett's ambitious reach is not fully realized.

At every point, though, the novel's emotions are very strong. Its details are very good. Its story is compelling and its conclusion is crushing: Bodo may have been rescued but not saved.

|

by Alex Carey University of Illinois Press, 1997 215 pages |

Trouble is, the "Theys" of the world almost always manage to maintain their anonymity. In Taking the Risk out of Democracy: Corporate Propaganda versus Freedom and Liberty, Australian-born sociologist Alex Carey rips the masks off many of these social engineers.

Published posthumously as part of the Robert McChesney-edited series "The History of Communication," Carey's essays were developed out of a year's worth of research with Noam Chomsky. Carey, who died in 1988, was one of Australia's most articulate defenders of free thought, free speech, and civil rights. A lecturer on psychology and industrial relations at the University of New South Wales, Carey helped found the ACLU-styled Australian Council for Civil Liberties and the Australian Humanist Society.

With clarity and rock-solid analysis, Carey traces the evolution of the American corporate and political propaganda movement. It all began in 1917, with the United States' entry into World War I. In desperate need of public support, President Wilson orchestrated a massive and successful anti-German - or rather, anti-"Hun" - propaganda campaign. America's business establishment was so impressed that it recruited Edward Bernays, Wilson's propaganda maven and a nephew of Sigmund Freud, into its service.

It was Bernays who years later penned these chilling words, which helped earn him a major award from the American Psychological Association: "It is impossible to overestimate the importance of engineering consent. The engineering of consent is the very essence of the democratic process. It affects almost every aspect of our daily lives."

With the help of Bernays and other pioneering propagandists, corporate America made efficient use of the propaganda tool. The first test came with the Great Steel Strike of 1919. In their efforts to sway public opinion, management left no anti-union levers unpulled. Organized labor was simultaneously accused of being the handiwork of the "Huns" and the "Reds." Industrialists brilliantly capitalized on the Red Scare, pressuring unions to be purged of communists and leftist sympathizers alike. Every major U.S. institution - from the church to the media-took the propagandist bait.

Along with Bernays, political scientist Harold Lasswell gave these new propaganda techniques legitimacy. "More can be won by illusion that by coercion," Lasswell once declared. "Democracy has proclaimed the dictatorship of [debate], and the technique of dictating is named propaganda."

Journalist Walter Lippman, who served with Bernays in President Wilson's propaganda headquarters, referred to regular people like you and me as "the bewildered herd." Lippman once wrote, "The manufacture of consent was supposed to have died out with the appearance of democracy. But died out it has not.... Under the impact of propaganda, it is no longer possible to believe in the original dogma of democracy."

Carey documents how Bernays, Lasswell, Lippman, and their brethren helped forge a bona fide propaganda industry. Among its early financial patrons was the National Association of Manufacturers. After surviving a 1913 congressional investigation that warned of the "genius and fear" associated with its propaganda, the NAM became instrumental in the birth of such sophistic social sciences as "industrial psychology," "human relations," "neo-human relations," and "human resources."

NAM's many triumphs include the passage of the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which significantly rolled back gains the Wagner Act achieved 12 years earlier. To marshal anti-labor sentiment, the NAM and U.S. Chamber of Commerce led a propaganda machine that churned out millions of patriotism-laced pamphlets and op-eds, corralled the nation's workforce into "economic education" classes (which even Fortune magazine labeled "indoctrination"), and rammed through legislation establishing the Fourth of July as an official holiday. (Carey provides a fascination history of how the Fourth was initially proposed in 1915 as an "Americanization Day" designed to turn recent immigrants against unions.)

The NAM also worked closely with the nefarious-sounding (and behaving) Psychological Corporation. Twenty prominent psychologists founded the organization in 1921 to gather public-opinion and other intimate psychological data on the nation's consumers and workers, and then sell it to corporate America. Thus were born such now-ubiquitous tactics as target marketing, human resources, and damage control. Among the organization's top objectives was to change the symbols used to describe business performance while bringing about "no change in actual performance."

In the workplace, management began to "encourage active participation" by employees while being careful not to actually grant them additional rights. One such tactic was the creation of small "work groups" or "teams" designed to lead people to identify with the goals of the corporation rather than unions.

Why do Americans seem so uniquely susceptible to propaganda? Beyond some of the more obvious explanations, Carey poses that since Americans are primarily Christians, they are susceptible to "a worldview dominated by symbols and visions of the Sacred and the Satanic." The secular translation of this, Carey says, is a struggle between various earthly manifestations of Good (free-market capitalism) against Evil (i.e. socialism). Such black-and white visions in turn squeeze out the real debates necessary for a vigorous democracy.

|

|

|

|

|