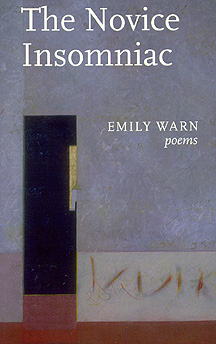

The lucidity of the poems in The Novice Insomniac also measures time, the painstaking time Warn has taken to get the words clear and right. In so doing she fulfills the poet's true task, which as T.S. Eliot learned from Stˇphane Mallarmˇ is "to purify the dialect of the tribe." Listen to the first three lines of her poem "After Starting a Forest Fire:"

The first line is simple and evocative, in the way that William Stafford was a master at. We can imagine the languid air; we want to imagine a couple wiling as couples will; but yet something is about to happen. The second line holds the suspense-we're not yet to be told-instead Warn gives us a vision of a place, "upriver," and we imagine a river we've followed in a wilderness we've entered. And she names that place "of the deer," and we can feel the bent grass warmed by a doe's body and that brings us sensually back to the we a-laying.

The first line is simple and evocative, in the way that William Stafford was a master at. We can imagine the languid air; we want to imagine a couple wiling as couples will; but yet something is about to happen. The second line holds the suspense-we're not yet to be told-instead Warn gives us a vision of a place, "upriver," and we imagine a river we've followed in a wilderness we've entered. And she names that place "of the deer," and we can feel the bent grass warmed by a doe's body and that brings us sensually back to the we a-laying.

What began simply is now complex; the images of love and earth, river and fire are superimposed; the song of the couple has harmonized with the song of the "scarred but still living" earth.

Warn is acutely aware of natural beauty, but the question for her is "How do you bear such beauty?" Her poem "Evening Prayer" begins "I taste the bitterness of acorns," and that is emblematic of her sensibility. As I read and re-read her poems, they carve out a place in me of exquisite emptiness where "clarity returns, rainwashed, windstripped."

The title poem of The Novice Insomniac playfully describes the "hours of slate" when awareness is painful, when insomnia becomes a vocation. The Novice Insomniac learns how to hold the night in a box, how to hold all those who are sleeping in her lap, how to spin the stars before dawn. Warn details the malady's soft suffering in poems on "The Genesis of Insomnia," "On the Insomniac's Watch," for "The Insomniac Ward," and for the "Rusted Hinge Bed and Breakfast." Insomnia is a work-related injury for Warn, who takes such careful looks at the hard world. Her poems are always awake and stronger than coffee.

|

|

Emily Warn |

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the March/April, 1997 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1997 WFP Collective, Inc.