REEL UNDERGROUND

REEL UNDERGROUND

FILM REVIEWS

AND CALENDAR

Zhang Yimou's Best and Worst Return to the Varsity

"Raise the Red Lantern" and "Shanghai Triad"

directed by Zhang Yimou

November 26 at The Varsity Theatre

by Paul D. Goetz

Free Press staff writer

In 1991 audiences were fortunate to witness the arrival of an extraordinary new master of the cinema, Chinese director Zhang Yimou. With "Raise the Red Lantern," Zhang gloriously fulfilled the promise of his previous films, "Red Sorghum" (1987) and "Ju Dou" (1989). Truly his most mature work, "Raise the Red Lantern" has proved to be his masterpiece.

Zhang makes visually stunning tragedies that often feature young women of the 1920s whose universal human desires are caught in the jaws of inhumane and uncompromising Chinese traditions. His is a relentless attack on customs cemented by thousands of years of feudalism - customs that continue to quash the soul. While many of his films have been banned in China, he continues to provide eloquent metaphors for the ways the contemporary Chinese government oppresses its people.

In "Raise the Red Lantern," the lovely and talented Gong Li (she has starred in many of Zhang's films and has evolved into an extraordinarily accomplished actress) plays Songlian, a Chinese woman of nineteen whose opportunity to attend a university is cut short when her father dies. Under her stepmother's pressure and the thought of life's severely limited options, she impulsively decides to become the fourth concubine of a wealthy man. Here, Zhang photographs his actress in close-up as she stares into the camera, the gravity of the situation pulling her character down into a growing sorrow that breaks upon us in a wave of emotion. Rarely has any actress so fully acquired our empathy and so deeply illuminated her character less than three minutes into the narrative. Rarely has any film been so engaging this early.

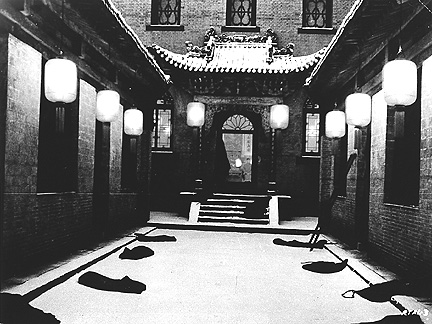

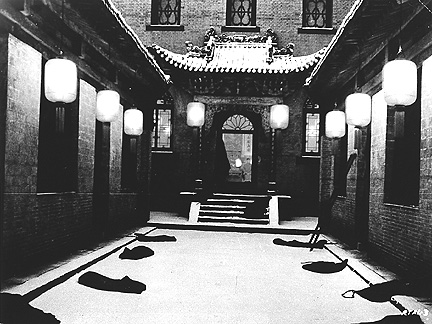

Thinking that this new station in life will at least afford her the power and pleasures of wealth, the respect of her husband, and the control of her servants, she soon finds the opposite to be true. To be sure, each wife is given her own beautifully furnished house within the walls of an immense estate, all in close proximity and connected by a common courtyard. Each is attended by servants and a housekeeper, and each is clothed and fed in keeping with the wealth of the household. Almost every moment of their lives, however, is controlled by family customs, some of which are grimly humorous, all of which have a corrosive, dehumanizing effect. Following the evening meal, the mistresses must wait in the common courtyard for instructions from the master. Soon, a servant places a large, bright red lantern in front of the mistress who will be visited by the master that night. The housekeeper then calls to the servants who light nearly a dozen lanterns in front of the chosen wife's house. Before the master arrives she is given a foot massage, and the next day she is allowed to set the menu for the meals. It's one of the few decisions she's allowed to make.

The master has no sincere respect for his wives. He uses them as long as they are young and attractive, hoping they will give him sons, only spending time with them on the nights they are chosen. He also holds a threat over them as evidenced by the room where some disobedient wives were apparently hung. We never see the master's face in close-up. Faceless, ruthless, and superficially placating, he represents the absolute power of the state.

Songlian soon finds that the other mistresses and servants are not what they seem. Locked in a deceitful struggle for the attentions of the master, they don't realize they are cogs in a machine that attempts to erase their faith, destroy their hope, and transform their souls into subservient shadows. They are human beings whose self-concepts are turning ghostly.

Outside shot from Zhang Yimou's "Raise the Red Lantern"

Though nearly all the action takes place within the confines of a massive, gray brick estate, the film never feels tight or set-bound. The film is severely diminished on video; in its own way, it's as exuberantly cinematic as Bernardo Bertolucci's "The Last Emperor." The glow of the lanterns, in particular, is almost impossibly exquisite.

Instead of several rooms within a single large building, there are several buildings, elaborately connected by sloping roofs, balconies, terraces, and courtyards. Zhang and his cinematographers, Zhao Fei and Yang Lun, exhibit an impeccable sense of design as they fluidly follow their actors through a maze of passageways, up and down stairways, and along multi-leveled roof-lines from which there is no escape.

Though there are several sequences on the roof, we rarely see the outside world, and the sky is lifeless - the intention being to limit our vision to the inner workings of a dehumanizing machine, or perhaps the inner workings of an elaborate clock within which time has no meaning. The film's plot is, after all, organized around the changing seasons - the evidence of which is provided by titles and a single winter snowfall - and the periodic lighting of the lanterns.

Most of the film's stylistic and narrative elements are richly ironic, from the lighting of the lanterns which is fraudulently celebratory, to the elaborate meals suggesting last suppers for death row inmates, to the estate itself, artfully photographed to depict either a grand palace or a suffocating mausoleum.

Most of the scenes in Ni Zhen's eloquent script do double duty, illustrating a multi-layered complexity that is never unnecessarily complicated. Songlian's one tangible link with her past is a flute which was a gift from her late father. One day she is drawn to a high, spacious, wind-swept room by the beautiful sound of a flute. There she stands in the doorway listening to the playing of the master's handsome son Feipu. And as she listens, Gong Li conjures and couples for us what must be Songlian's joyful memories of childhood, when her father played his flute for her, with a new intense desire to escape her imprisonment with this beautiful young man. The words they share are brief and formal; it's obvious they belong to separate worlds, and as they part, we hear a flute and see Songlian look back at Feipu, realizing that the sound comes not from his flute but out of her profound remorse for a past that is gone forever and for a future that will never be. Doubly acute, it's a scene that will forever burn in the memory.

"Red Sorghum" and "Ju Dou" established Zhang as an extravagant, artful filmmaker. Powerfully indelible, they are almost excessively exclamatory. Their exaggerated conflicts and pointed emotions have encouraged comparison with Hollywood melodramas of the 40s, while Zhang's almost self-indulgently lavish use of bright, primary colors has, at times, over-emphasized exterior surfaces at the expense of interior meanings.

There is some evidence that Zhang's ability or freedom to focus his powers may be waning. "The Story of Qui Ju" (1992) and "To Live" (1994) were steady and substantial yet neither achieved the fusion of style and substance that made "Raise the Red Lantern" a transcendently absorbing experience. His latest film, "Shanghai Triad" (1995), is his first failure.

It concerns Shuisheng (Wang Xiao Xiao), a 14-year-old country boy who, because of his family ties, is taken in by a powerful gangster (Li Baotian looking conspicuously like Chiang Kai-shek) to be the servant of his mistress Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), a singer in his lavish nightclub. After a rival's attack wounds the boss, the gang is forced to flee to a remote island where Shuisheng's abhorrence for Xiao Jinbao softens when she begins to reveal and pine for her own rural past. Zhang achieves a measure of poignancy as we begin to see how their tragic fates compare and intertwine, but through most of the film, Shuisheng is little more than an observing cipher while Xiao Jinbao's vanity and contempt make it difficult for her to win our sympathy.

Zhang intends an allegory, identifying the contemporary Chinese Party as a government by gangsters that absorbs and crushes its people, but it's a schematically drawn connection. Zhang seems enthralled with the superficial machinations of gang conflict, and though the film has been lauded for its cinematography, the exquisite sheen it captures is emptily beautiful.

"Raise the Red Lantern," on the other hand, is a nearly perfect wedding of style and substance, marrying its fundamental premise with every twist and turn of the plot. The film's interior meanings become synonymous with its visual imagery. While retaining a skillful stylistic vitality, it never detracts from the story's quietly evolving inevitability. Though color continues to play an important role, the absence of color is equally significant, and both draw our attention to meanings rather than surfaces.

The film transports us to a foreign time and place, yet its universal messages, that there can be no meaning without freedom, that oppression not only destroys individuals but transforms them into destructive entities, make it significant and heart-rending. The great depth to which this tragedy has been illuminated could only be accomplished by someone with an extraordinary sense of the preciousness of freedom. We can only hope that Zhang will return to nurture this sense and courageously continue to bring his vision to the screen.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the November/December, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.