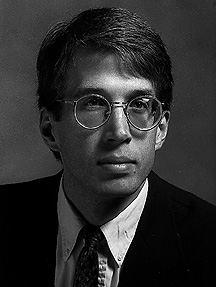

ALAN DURNING

OF NW ENVIRONMENT WATCH

INTERVIEWED BY MARK GARDNER

THE FREE PRESS

The businessman looks ahead to the next quarter's profits, the politician to the next election. Who looks out for the future of the earth? Northwest native Alan Durning has spent his entire career focusing on the trends, positive and negative, that are shaping our future. Durning joined Washington, D.C.-based Worldwatch Institute right after college, and helped call our attention to the connection between social injustice and environmental degradation, and to the costs of overconsumption. In 1993, Durning returned to the Northwest to start Northwest Environment Watch (NWEW) to do for our region what Worldwatch does for the world.

The businessman looks ahead to the next quarter's profits, the politician to the next election. Who looks out for the future of the earth? Northwest native Alan Durning has spent his entire career focusing on the trends, positive and negative, that are shaping our future. Durning joined Washington, D.C.-based Worldwatch Institute right after college, and helped call our attention to the connection between social injustice and environmental degradation, and to the costs of overconsumption. In 1993, Durning returned to the Northwest to start Northwest Environment Watch (NWEW) to do for our region what Worldwatch does for the world.

What was your role at Worldwatch, and what brought you back to Seattle?

In high school I decided I wanted to be a professional trombonist and sit in the back of the orchestra counting rests. In college in Ohio where I was studying music I heard a guy named David Orr, an environmental educator who was at the time setting up an environmental education center in the poorest county in Arkansas caused Meadow Creek. Orr gave an Earth Day speech in 1981 saying that we need to create a new culture because the current one was going to go down in flames. So that sounded like a call to action. I went off to Central America for a few months to learn Spanish better, which ended in my getting an immersion in third world poverty. I then flew straight to Washington D.C. to start a research assistantship at Worldwatch Institute.

You've talked about our descent into a new dark age.

That's if we don't make some changes. At Worldwatch for the first several years I basically earned my doctoral equivalence by researching everything from nuclear power to third world agriculture, with a variety of senior researchers on the staff there. I then graduated into doing my own research, and I tended to focus on economic and social inequalities on the one hand and environmental degradation on the other. I've always been obsessed by the question of how to reconcile our relationship to natural systems while we're treating people more fairly. So I did studies on poverty and economic inequality, on indigenous cultures, and I did a study on grassroots development and environmental protest movements all over the world.

I looked at the social justice conflicts that were going on in the tropical rainforest regions, and helped to cast a bright light on those issues at a time when the debate in the North was framed around the preservation of biological diversity, without an understanding of the social context of gross inequality and maldistribution of land. While I believe that things are going to get substantially worse if we don't make major changes, I've always ended up being inspired by the individuals and groups of individuals who in the face of great adversity create good alternative models to the status quo. I found examples of that in just about every realm, certainly in developing countries. I came back inspired and with a renewed faith in humanity after traveling to dirt-poor parts of developing countries and finding people who could speak much more eloquently than I could about how to protect our inheritence while attending to our true needs.

Around 1991 I turned my attention from the bottom to the top of the economic ladder, and looked at the question of consumption of natural resources. The result was the book How Much is Enough?, a study of the consumer societies of the world - really the top fifth of the world's economic ladder - roughly one billion people who cause the overwhelming majority of the damage to global common resources like the climate and the oceans, and that consume an overwhelming majority of all natural resources. That was pretty influential in my own work because it became a frame for much of what I've done since. That book was a success and was widely read, putting me on the lecture circuit and in enormous demand to travel around the world talking about it. There was a terrible paradox of burning thousands of gallons of jet fuel to talk about overconsumption. I went to the Netherlands for 36 hours once and Germany for 18, and that started to suggest to me it was time to move from being a jet setter for future generations, to being more settled in place, and to work more specifically in the society and the place in which I grew up and to which I remain connected by emotional and family bonds. I wanted to try to facilitate change in one place, in the hopes of making this place a model in the industrial world, or at least in North America.

So in 1993 I came back home to Seattle and started Northwest Environment Watch with the assistance of lots of people, and began a series of publications that would help give Northwesterners the information they need to make informed decisions about sustainability.

What do you see as NWEW's primary mission?

Our mission is to foster an environmentally-sound economy and way of life for the Northwest and thereby set an example for the world. It's a modest mission. Our function is to be a purveyor of accurate and change-making information. There's too much information in our world, we're bombarded and lambasted with information, and our minds have not evolved quickly enough to keep up with the information age. So we're not just trying to add more information to the stream, we're trying to be an antidote to information overload - distilling, synthesizing, and analyzing available knowledge about the relationship between people and this place, and providing some guidance on what are the highest priorities and the next steps toward a way of life that works within the design of nature.

We do it in three different types of publications, one is a book called This Place on Earth, it'll be out in October, published by Sasquatch here in Seattle and distributed all across North America at least. This Place on Earth is a serious book about public policy and our future and our culture, and it's also my personal story about coming home and trying to figure out what permanence really means in the mid-1990s in North America, when connection to place is at most a distant memory.

Second, we do shorter books that are policy- and action-oriented. We just put out the third called The Car and the City that looks at how to build cities where cars are adjuncts to life rather than substitutes for our feet. Before that we did a book called Hazardous Handouts, authored by our research director John Ryan, which provides a scathing indictment of current public policies, showing that it is not just that the free market isn't respecting the environment, but also that taxpayer dollars by the billions are spent to encourage resource-wasting, polluting economic activities. We subsidize people to drive, to mine, to clear-cut, to build houses in floodplains, and at the same time we tax people for working and saving money.

Before that we did a book called The State of the Northwest which is a physical health exam of the Pacific Northwest bioregion. It's about 200 years since light-skinned people arrived here and it seemed like a good time to take stock of the health of the natural underpinnings of the economy.

Our third publication series is called "New Indicators" where we try to provide an antidote to the Dow Jones Industrial average and the Consumer Confidence Index. Every few months we release data on a trend of enormous significance to this region. We track sustainability by the numbers. In the first we looked at what share of jobs in the region come from resource-extraction industries. It's not many, about four percent of all jobs in the region now are in logging and mining, one seventh as many as are in service industries.

We looked next at the car population in the northwest - there are now more cars than licensed drivers by a million. Then we looked at the region's emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, and showed that the region is well on the way to violating the climate treaty signed in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. And most recently we released an indicator showing that the Northwest now has more miles of roads than it has miles of salmon streams, enough roads to wrap around the equator 29 times. Five-sevenths of those roads are logging roads, most of which should probably be closed and ripped out.

From your analysis of "Hazardous Handouts," what would you say are the most egregious forms of corporate welfare for polluters, or tax incentives for waste?

There are probably 50 or 60 examples in the book. We subsidize farmers to not grow crops while subsidizing irrigation water for those crops, and then we pay for the Corps of Engineers to dredge out the channels where the soil that runs off of those fields ends up, and then we pay for fish hatcheries to try to replace the salmon that have been demolished by river basin developments including dams and irrigation. And then we have to pay millions of dollars for salmon recovery efforts - fisheries biologists and multimillion dollar taskforces to try to figure out how to save the fish from the fish hatchery salmon that are outcompeting the wild salmon.

We're paying every step of the way, it always ends up back on the taxpayer. The book ends up sounding like a conservative tract - small "c," old-fashioned conservative, fiscally-conservative, prudent, pinch pennies. We could save tax dollars, improve the business climate, and protect the environment at the same time. It's distressing how far the public policy discussion is from that.

WFP's Previous NWEW Coverage

and...

"The Consequences of a Cup of Coffee"

(co-written by Alan Thein Durning)

|

|

|

|

|