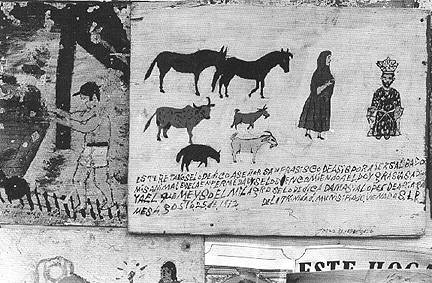

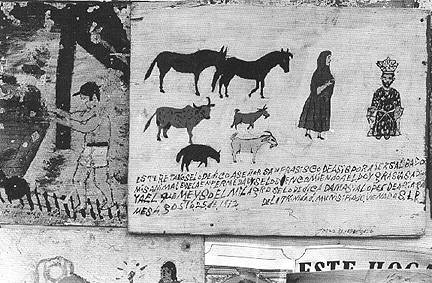

This photo by Seth Thompson cannot be sold as a postcard in Mexico without the express written permission of the Catholic Church

"The least greed is down at that author level. Whatever amount of money is involved, he's going to be more reasonable than publishers." -Bill Gates, in a 1993 meeting of Microsoft executives discussing how to get the material they need to provide the content for multimedia software. (From I Sing the Body Electronic by Fred Moody)

An artist's response to Gates's assessment of intellectual property can go two seemingly contradictory ways: 1) With his market share, profit margins, and penchant for snapping up the electronic reproduction rights to art the world over, he's the last person to call anyone greedy! and 2) What's so unreasonable about greed? While there's something inherently despicable about some tycoon owning and leasing out works done by artists who, in many cases, made little from their creations, the same laws Gates uses to acquire intellectual property can be used by artists to cash in on their own works.

For most artists, recent changes in U.S. copyright laws have made life easier. Simply make something and you hold its copyright. Of course, filling out Form TX (write to: Register of Copyrights, Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559-6000) and paying $20 to stake a claim on your own title is the best evidence in the event of a challenge. Also, since the Supreme Court clarified what constitutes Fair Use in the 1992 case of 2 Live Crew's "Oh, Pretty Woman," artists and others have been somewhat freer to quote, parody, and otherwise make use of copyrighted material than they were previously.

Attending these changes is an expanded awareness of the marketability of things which formerly might not have seemed to qualify as property. The naming rights to basketball arenas, a celebrity's right to control publicity, and the right to claim ownership of the DNA of an Amazon tribe wonderfully exhibit the possibilities generated by the drive to make a buck. Creative as these interpretations may be, they speak more to owners protecting their interests than to creators protecting their works.

While the richest man in the world praised authors who sold their work below market level, Seattle painter and photographer Seth Thompson also approached the problem of how to earn a living from art. He went to Mexico and took photographs of devotional paintings in churches. Back in the States he had the prints developed and made into postcards. And then, not to be greedy or unreasonable, Thompson went to the church in Real de Catorce, San Luis Potosi, where he had previously asked permission to take photos, and offered to pay for the rights to sell the postcards. He offered to let them sell the cards, since they already had a healthy trade in religious gewgaws, featuring their patron Saint Francis.

The Church said no. The local church in this town of 1000 referred him to the bishop, and after six months the ruling came down. They wouldn't sell the cards or allow him to sell the cards; plus, they wouldn't let him take any more photos of the inside of that church, or in any of ten other churches in the parish. He could exhibit his prints in a gallery, but the Church wouldn't allow any commercial reproduction of the photos as postcards or even in the form of a scholarly book.

"When I said, 'This is art!' the priest said, 'I don't see where the art is,'" Thompson refers to one of their more straightforward disagreements.

The Church's main objection was that commercializing these images betrayed their nature. After all, devotional paintings (retablos) are paintings commissioned by people to thank or honor a saint. These gifts from patrons to the local church are mostly painted by unskilled artisans, whose names are usually omitted from the plaque commemorating the act of devotion. A few of the paintings Thompson saw were quite good. The local church had even sent some of these to a museum exhibit in Mexico City, contradicting their dismissals of the works' artistic merit. Also, by removing the paintings the church violated their main objection to his use of the paintings, Thompson argued, since they were putting the paintings to a use the donors had not intended.

The contract Thompson signed with The Church can't prevent him from selling postcards in the U.S., so there's a slim chance his foray into intellectual property speculation won't be a total loss. He spent about $650 each for four print runs of cards he had planned to retail for about .75 a piece. Changes in the Mexican photo processing industry had created a need for good-quality postcards, and although Thompson's artistic compositions deviated from tourist shot standards, he had hoped to earn enough with his photos to be able to continue to live in Mexico, working on his art.

Thompson's photo reproductions of the work of unskilled painters succeed as artworks in their own right, but some might question Thompson's right to make even a reasonable living off these pieces. Ownership be damned, what about the artists' rights?

"If someone made a postcard of my work, I'd be hopping mad," he says. The difference he sees between his own paintings and those retablos is that his paintings are clearly authored works of art.

|

|

|

|

|