Clearcuts and Corporate Welfare

Sweetheart land deals and bailouts hide the true cost of corporate logging.

by David Atcheson

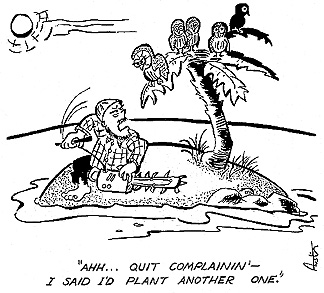

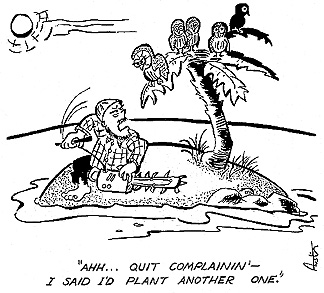

illustration by Ron & Emily Austin

Free Press contributors

When considering logging in Washington state as a form of corporate welfare, it helps to take into account the 1864 Northern Pacific railroad land grant.

In 1864, Congress granted the Northern Pacific 40 million acres of land (an area nearly as large as Washington state) to support the construction of a railroad from Lake Superior to Puget Sound. The lands were granted in a checkerboard pattern of alternating square miles within a swath between 40 and 80 miles wide (80 miles in Washington) and 2,000 miles long.

One of the conditions established in an 1870 revision of the grant was that the lands be sold to homesteaders within five years of the completion of the railroad, for not more than $2.50 per acre. This condition was not met, and most of the millions of acres of grant lands were sold instead to timber interests like Weyerhaeuser for bargain-basement prices.

A recent book, Railroads and Clearcuts, by Derrick Jenson and George Draffan, with John Osborn, M.D., underscores the significance of this grant in the Pacific Northwest forest crisis. The book documents the legal basis for private ownership of millions of acres of formerly public Pacific Northwest forests by logging concerns such as Plum Creek and the Weyerhaeuser corporate empire (which includes Weyerhaeuser, Potlatch, and Boise Cascade).

Within five years of obtaining grant lands from Northern Pacific in 1899, Weyerhaeuser gave Washington the dubious distinction of being the nation's leading producer of timber. Weyerhaeuser alone has cut four million acres total since 1900.

Below-cost Timber Sales

In 1984, the Forest Service established an accounting system to track costs and revenues for its timber sale program, known as the Timber Sale Program Information Reporting System (TSPIRS). The system has brought to light that the timber sale programs in many national forests lose money. Often, the costs to the U.S. Forest Service in preparing and administering the timber sales exceed sales revenues.

Janice C. Shields, of the Center for Study of Responsive Law, analyzed the 1994 TSPIRS report and found that 50 of the 121 forests (41 percent ) lost money in the "timber" component, and 63 of the forests (52 percent) lost money in the "stewardship" (read "salvage") component. The losses in these forests totaled $40 million.

Janice C. Shields, of the Center for Study of Responsive Law, analyzed the 1994 TSPIRS report and found that 50 of the 121 forests (41 percent ) lost money in the "timber" component, and 63 of the forests (52 percent) lost money in the "stewardship" (read "salvage") component. The losses in these forests totaled $40 million.

Under the Forest Service's accounting system, the overall timber program appears to make money. There is no dispute, however, that a large number of sales cost more than they return to the U.S. Treasury. To Senator Larry Craig (R-ID), a major proponent of "salvage" logging legislation, that's not a problem. In June of 1993, he enumerated his reasons for keeping the below-cost sales to a congressional subcommittee on conservation and forestry. He argued that besides being a tool in maintaining forest health, below-cost sales create jobs both directly and indirectly (which in turn generate tax revenue), and reduce our demand for foreign timber.

Opponents emphasize the indirect costs of these timber sales in the form of increasingly fragmented forests, habitat loss, and sedimentation of streams and rivers.

Roads to Ruin

Several watchdog groups do not buy Craig's arguments for maintaining below-cost timber sales. One of the most expensive and damaging elements of the timber sale program, road building, has been targeted for defunding. In June of 1995, Essential Information, together with the CATO Institute and the Progressive Policy Institute, released a Dirty Dozen list of federal subsidies to cut from future budgets. The groups recommended the elimination of the Forest Service road construction budget to curb sales of timber from public lands to private companies. Cutting the road budget would save roughly $600 million over five years.

It is difficult to overstate the impact that forest roads have on the landscape in Washington and throughout the Pacific Northwest. The sheer number of miles is staggering. A December 1995 report by Northwest Environment Watch (NEW) says that "national-forest roads have proliferated since 1960, more than tripling in Oregon and more than doubling in Idaho and Washington." In Washington, national-forest roads have grown from about 9,000 miles in 1960 to 22,000 miles today.

Alan Durning, executive director of NEW, remarked, "Perhaps the most surprising finding is that roads have surpassed streams as the most dominant feature of the landscape in the region....Today, outside of Alaska, more of the U.S. Northwest is accessible to four-wheelers than to salmon."

Logging roads hasten erosion and damage fish-bearing streams. New road construction techniques are having some success in mitigating negative effects, although these improvements may be canceled out as roads are built into increasingly steep and fragile areas to get at remaining timber.

Moreover, new techniques don't mitigate the legacy of existing roads built to outdated specifications. Declining budgets for road maintenance makes the problem worse. The Forest Service has allotted only $22 million for road maintenance in the Northwest for 1996, compared to $71.2 million in 1985.

According to the Oregonian, the Forest Service estimates that the current budget is half of what's required. Without adequate funding to clear culverts and ditches and correct other problems, the Forest Service is unable to prevent slides and wash-outs in heavy rains.

Flood Damage Bailout

In Washington, the November '95 and February '96 floods caused a combined $385.5 million in damage, dwarfing the $77.6 million in damage done by the November 1990 floods. Estimates of damage to the national forests in Washington and Oregon exceed $60 million.

The heavily-logged Gifford Pinchot National Forest was hit particularly hard. According to New Ground, newsletter of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, "preliminary damage estimates range from $10 million to $14 million....Numerous roads, bridges, trails and recreation sites Forest-wide were damaged, and access into the Forest is limited" due to washouts. The damage to flooded hatcheries and spawning grounds of wild salmon was equally extensive.

With the ground saturated from the November storms, flooding and mudslide activity from the February storms were inescapable. However, evidence abounds that heavily logged areas fared much worse.

A 1980s study in the North Cascades by University of Washington hydrologist Dennis Harr stated, "In conditions similar to the 1996 flood, characterized by heavy rains and warm winds on snowpack, clearcuts produced 10 times the runoff of mature forests. And younger forests pumped out 40 percent more water than older forests."

Immediately after the February storms, members of the Association of Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics (AFSEEE) flew over the Oregon Coast Range's Mapleton Ranger District of the Siuslaw National Forest to inventory slides. The Mapleton District makes an especially relevant study site because in the mid-1980s it was subjected to the same kind of suspension of environmental laws that is now the rule with the "salvage" rider. The AFSEEE Activist reported, "We counted 185 slides, 114 from clearcut areas, 68 from logging roads, and 3 natural, in-forest slides...."

Environmental groups have responded to the evidence linking logging to flooding by calling for a General Accounting Office (GAO) study of the issue. Many feel that clearcutting continues because the timber industry is allowed to externalize environmental costs of logging and to transfer costs of flood relief, municipal water filtration, and fisheries restoration onto taxpayers.

Victor Rozek, general manager of the Native Forest Council in Eugene, told Eugene's Register-Guard, "If the timber industry was forced to bear its fair share of the cost of this year's flood damage, you could be sure that massive clear-cutting on steep slopes would cease."

Lax Laws

A GAO investigation could ultimately result in new laws that would force the industry to internalize the environmental costs of logging. Meanwhile, the industry benefits from a relaxation of laws already on the books. A prime example is the infamous "salvage" logging rider, which opponents have called "Logging Without Laws" for its suspension of environmental laws.

Others have pointed to the dissolution of the highly successful Timber Theft Task Force to suggest that the government is not fully committed to enforcing laws governing timber corporations. The task force was founded by the Forest Service in 1991 to crack down on timber companies suspected of stealing trees from public lands in California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska. In 1993, efforts by the task force led to eight felony convictions and $3.5 million in fines.

But in 1994, agents felt that their efforts were being thwarted by regional managers, and ten of the seventeen agents sent a written complaint to Forest Service Chief Jack Ward Thomas. In April of 1995, Forest Service law enforcement director Manuel Martinez informed the task force that it was dissolved and "integrated into the regular law enforcement program." Andy Stahl, executive director of AFSEEE, remarked, "Now we're returning to precisely the same model that proved itself incapable of working."

In the context of the 1864 Northern Pacific railroad land grant, lax law enforcement applied to the timber industry is nothing new. The "salvage" logging rider and the dissolution of the Timber Theft Task Force are recent manifestations of a continuing pattern in which public lands are used to subsidize industry in ways the public never intended. Redressing the 1864 land grant, the mother of all timber subsidies, would signfiicantly reduce the subsidies we currently pay in the form of below-cost timber sales and flood costs created by roads and clearcuts.

The writer, David Atcheson, is active with the Pacific Crest Biodiversity Project.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the July/August, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.

Janice C. Shields, of the Center for Study of Responsive Law, analyzed the 1994 TSPIRS report and found that 50 of the 121 forests (41 percent ) lost money in the "timber" component, and 63 of the forests (52 percent) lost money in the "stewardship" (read "salvage") component. The losses in these forests totaled $40 million.

Janice C. Shields, of the Center for Study of Responsive Law, analyzed the 1994 TSPIRS report and found that 50 of the 121 forests (41 percent ) lost money in the "timber" component, and 63 of the forests (52 percent) lost money in the "stewardship" (read "salvage") component. The losses in these forests totaled $40 million.