Light Up. Be Cool. Drop Dead.

Story by Mark WorthPhotos by Pete Lemaire

Research assistance by Mike Blain, Margaret Flynn, and Eric Nelson

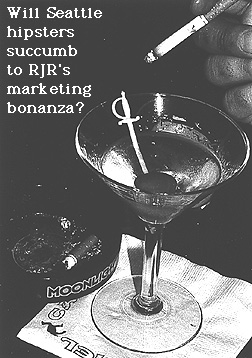

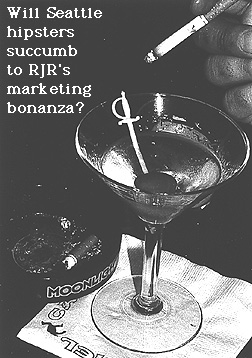

If Seattle is cool enough for lounge music, late-night espresso bars, retro fashion and body art, what's stopping cigarettes especially designed and packaged for Twentysomething hipsters from becoming the latest trend? It's a high-stakes question that RJ Reynolds Tobacco Co. has just begun to pose to the thousands of youthful smokers who live in Seattle. From full-color Moonlight cigarette ads in The Stranger and Camel merchandise catalogs distributed in the Seattle Weekly, to Moonlight martini glasses at Moe's nightclub in Capitol Hill and Camel ashtrays at downtown's Colour Box, RJR is deluging the city with a flashy public-relations campaign that is turning fad-driven, image-conscious smokers into marketing guinea pigs.

Club-goers in Pioneer Square and latte-sippers on Broadway may look hip while sucking on a Camel or fingering a Moonlight. But the fact remains that up to one-third of them will die from smoking-related illnesses. Ultimately, it will be up to these trendy smokers to decide whether they will become willing followers of RJR's propaganda, or if they'll see RJR's public-relations machine for what it really is.

It's the kind of campaign that has anti-smoking activists throughout the country worried. "Tobacco companies know that young people are trend starters," said Bill Novelli of the National Center for Tobacco-Free Kids in Washington, D.C. "Cigarette marketing has a really profound effect on them."

On closer inspection, RJR's advertising blitz is much more than just a marketing campaign. The company is not merely selling cigarettes. It's selling a lifestyle. Just as makers of cars, beer, soft drinks, movies, fashion, and, of course, rock 'n' roll have endeavored to define what is "cool" to America's impressionable youth, RJR and other cigarette companies have finally recognized that their very survival depends on having a hand in shaping Pop Culture. And that's exactly what RJR is trying to do, right here in Seattle - the Barometer of Hip.

On closer inspection, RJR's advertising blitz is much more than just a marketing campaign. The company is not merely selling cigarettes. It's selling a lifestyle. Just as makers of cars, beer, soft drinks, movies, fashion, and, of course, rock 'n' roll have endeavored to define what is "cool" to America's impressionable youth, RJR and other cigarette companies have finally recognized that their very survival depends on having a hand in shaping Pop Culture. And that's exactly what RJR is trying to do, right here in Seattle - the Barometer of Hip.

Though RJR's subtle tactics may be lost on the casual observer, experts know exactly what's afoot. "Tobacco companies are very shrewd," Gary Black of the Wall Street securities firm Sanford C. Bernstein told Newsday in March. "Camel is an alternative to Marlboro for 18- to 24-year-olds, and Generation X wants to be different."

Two P.R. firms with offices in Seattle are under contract with RJR to peddle and promote Camel, Moonlight, and soon-to-be reintroduced Red Kamel (which was discontinued in 1936). Orchestrated by Kevin Berg Associates and Dyce Friend Promotions, the high-budget campaign seems to be turning to The Stranger for its marketing research.

Dozens of nightclubs, coffee shops and restaurants that advertise in the weekly publication have been approached by smooth-talking P.R. agents, offering thousands of dollars in "promotional funds" in exchange for agreeing to allow their businesses essentially to become exclusive retail and marketing outlets for RJR cigarettes. The campaign has experienced only mild success thus far, though not for the lack of initiative by the two P.R. firms. Or, for that matter, for the lack of a little creative spin control (see related story).

RJR's advertising blitz, which kicked into high gear in mid-June, comes at a crucial time for the entire tobacco industry. For RJR - along with the entire tobacco industry - the pressure to sell cigarettes, maintain cash flow and score P.R. victories is hotter than ever. Here's why:

- With millions of older smokers either dying to quit or just plain dying, Big Tobacco is fully aware that its future (if indeed it has one) lies with the younger crowd. RJR's own marketing plan from 1990 acknowledges as much, as do internal corporate memos dating to the early 1970s. It's a smart strategy: 80-90 percent of all smokers start before they turn 18, and studies show that teens are three times more susceptible to cigarette advertising than adults.

- Government agencies are cracking down on Big Tobacco like never before, most notably by investigating cigarette company CEOs for lying to Congress, threatening to regulate nicotine as a drug, and proposing to slap more restrictions on cigarette advertising.

- Lawsuits filed by several states to recoup cigarette-related Medicaid costs and by long-time smokers seeking damages have begun to receive favorable responses by judges and juries throughout the country. In June, Washington joined the growing number of states suing large tobacco companies.

- According to whistleblowers and leaked documents, Big Tobacco has known for decades that nicotine is highly addictive, and that some cigarette companies apparently have been manipulating nicotine levels to deepen smokers' dependence on the substance.

As government officials, children's advocates and medical researchers become less tolerant of the cigarette industry, RJR and its corporate brethren are stopping at nothing to tap into the youth market. Their strategy seems to be working: teen smoking rates are at a 20-year high.

It's little wonder that Michael Pertschuk of Washington, D.C.'s Advocacy Institute said of Big Tobacco: "This is an industry which is in the same moral and ethical category as the drug cartel."

"A Sparkle in His Eye"

Lisa Kender opened the Lux Coffee Bar on First Avenue in Belltown about two years ago. She had a partner in the beginning, but that changed and now she runs the business herself. "I'm the owner - that's it," said the Long Beach native. "I run it my way."

Lux is a nice place, with gold-and-black painted walls, high ceilings, soft lighting and understated decor. There's not an SBC or Coke sign to be seen. A visit from a local representative of Kevin Berg Associates nearly changed all that.

One day in May, KBA rep Dennis Masel walked into Lux with a thick binder full of flashy, full-color ads, flyers and other promotional material. A handsome guy in his early 30s, his mission was to persuade Kender to throw a Camel-sponsored party - perhaps a barbecue or something with a motorcycle theme - if she would agree for seven months to sell only RJR cigarettes and deck the place out with Camel signs, displays, ashtrays, beverage napkins, matchbooks and the like. Masel said he'd pay up to $1,500 for the party and handle all the promotions, including (for some reason) advertising in Chicago and New York.

One day in May, KBA rep Dennis Masel walked into Lux with a thick binder full of flashy, full-color ads, flyers and other promotional material. A handsome guy in his early 30s, his mission was to persuade Kender to throw a Camel-sponsored party - perhaps a barbecue or something with a motorcycle theme - if she would agree for seven months to sell only RJR cigarettes and deck the place out with Camel signs, displays, ashtrays, beverage napkins, matchbooks and the like. Masel said he'd pay up to $1,500 for the party and handle all the promotions, including (for some reason) advertising in Chicago and New York.

"He had an answer for everything. He was really sharp, charming," Kender said. "He had a sparkle in his eye. He looked like he could get a lot of women."

Maybe so, but despite his best efforts, he couldn't get Kender to sign on the dotted line. "At first it sounded great, especially because I'm really struggling right now. But I couldn't see being dictated by anyone. I didn't want my place to look like a mini-mart. It wasn't worth the trade-off."

A close look at the five-page contract Masel wanted Kender to sign shows just how much dictating KBA and RJR intended on doing. For starters, Masel wanted the right to go into Lux whenever he wanted to hand out Camel hats, T-shirts, and lighters, and to dole out free cigarettes. Kender's employees would have been prohibited from wearing anything with a competing cigarette's logo on it, or from allowing customers to see them smoke anything but an RJR product. Kender would have been barred from using anything but Camel ashtrays and napkins; even blank ones were forbidden by the contract.

What seemed to be an attractive offer eventually made Kender wonder whether she'd be selling her soul. "I'm really non-corporate. And I don't smoke - I never have. I didn't want Lux to be labeled a big smoking place."

Masel also flopped at the Lava Lounge, just one block over from Lux on Second Avenue. There he gave the hard-sell to manager Sylvia Wiedemann. For her, the decision was a no-brainer. "Our clients are very conscious of corporate America. They are more politically active than a large majority of the population," Wiedemann said. "One thing we love about the Lava Lounge is that people aren't being sold here. It went against everything we believe."

Wiedemann said several things about Masel's pitch rubbed her the wrong way. He said KBA reps would be stopping in three times a week to make sure Camel accouterments we being displayed properly. "I didn't want someone coming in and saying, 'You don't have enough Camel ashtrays sitting out'," Wiedemann said. And, it was clear to her that Masel wanted bartenders to serve as de facto RJR salespeople by conspicuously smoking Camels. "It was a little personal," she said, adding that she saw through RJR's not-so-veiled marketing strategy. "They're obviously targeting the 'alternative nation'."

KBA's cutthroat tactics come as no surprise to people like George Dessert, chair of the American Cancer Society. "Competition among tobacco companies is primarily a battle of the brands for market share among youth."

Like Lux's Kender, the Lava Lounge's Wiedemann sent Masel packing without a signed contract. Masel was also snubbed by Gretchen Apgar, a co-owner of the Speakeasy, a Belltown cafe that features Internet access, live music, and political roundtables.

Masel was also shown the door by Moe's Mo' Roc'n Cafe, a popular music club on Capitol Hill. Moe's publicity director, Mickey Wright, did agree to allow Moonlight's P.R. firm, Seattle-based Dyce Friend Promotions, to put up a neon Moonlight sign and donate martini glasses with the Moonlight logo. Wright says that it's just a coincidence that the club's upstairs room is called the Moonlight Lounge, where hipsters listen to old Ann-Margaret and Dean Martin records and sip martinis.

Despite his involvement with Moonlight, Wright doesn't have kind words for RJR's latest campaign. "They brought in Moonlight stickers, playing cards, and other stupid stuff - to the point that it was getting annoying," he said. "Tobacco companies are like Mafiosi."

"Are You Writing Something Negative?"

Masel did manage to find friendlier audiences at several other trendy businesses (most of which, coincidentally or not, are run by males). At the Colour Box, co-owner Steve Johnson said he's agreed to distribute Camel lighters, hats and T-shirts, and that he's "providing KBA with a place to sell cigarettes." Johnson wouldn't say how much he's getting out of the deal.

Also working with KBA are the Alibi Room (a beer/wine bar at the Pike Place Market), the Buckaroo Tavern (a beer bar in Fremont), Ileen's Sports Bar (formerly Ernie Steele's on Broadway), Kid Mohair (a gay club in Capitol Hill), and Sit & Spin (a coin laundry, cafe, performance space in Belltown). Owners and managers of these businesses either refused to comment about their deals with KBA or didn't want to talk about the details. That's not surprising - there's a confidentiality clause in the KBA contract.

Managers of some of KBA's clients seemed downright paranoid when asked about the Camel campaign. "Are you writing something negative?" asked Kid Mohair co-owner Mike Klebeck. "Is there a problem?" asked a Sit & Spin manager, who identified himself only as Ed.

There's certainly nothing legally wrong with selling or advertising cigarettes, but some of KBA's tactics raise ethical questions. For example, KBA's Masel has apparently been less-than truthful in his pitches to would-be clients. He told Kender of Lux that Capitol Hill's Bauhaus Books and Coffee had come on board. However, Bauhaus owner Joel Radin said he has never even been approached by KBA. Masel has also dropped the name of the Nitelite, even though the drinking hole at the Moore Hotel downtown has not joined the promotion.

When contacted, Masel would not talk about his activities. He did had this to say when asked about his apparent misstatements: "I have definitely not told people anything that wasn't true," said Masel, who is being paid by a corporation whose CEO has sworn under oath that nicotine is not addictive. "When you talk to people, you have to be honest."

Attempts to reach officials at RJR in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, were unsuccessful. Phone calls placed to KBA's home office in Chicago went unanswered.

With offices also in New York, Los Angeles and Dallas, KBA specializes in "trend marketing." According to a December 1995 article in the South Florida Business Journal, KBA has "honed the art of integrating thought-out advertising campaigns with eye-catching promotions."

Agency president Kevin Berg encourages his employees to party with the young, hip crowd to keep tabs on what is cool (read: what sells). Besides RJR, Berg's client list includes Spin and Interview magazines, Spirit Water, and Amerifit/Strength Systems (a Vancouver-based sport nutrition company).

Give The People What They Want

Hyperbole has and always will continue to be the bread-and-butter of cigarette advertising. During the 1930s, ads claimed that smoking was good for the digestive system. In the '40s, one brand boasted "each puff is as cool and refreshing as a frosty drink."

In the decades that followed, as medical evidence debunked such claims while revealing that tobacco actually wreaked serious physical harm, Big Tobacco began espousing the social benefits of smoking. You could meet a handsome husband or a gorgeous wife, land that perfect job, and meet the right friends - just based on the brand of cigarette that dangled from your mouth.

Now, in the late 1990s, RJR and its minions are pushing this evolution to the next level. The messages are more vague, complex, postmodern, though no less persuasive. "Cigarette companies are the world's best marketers," said Joel Cohen of the University of Florida's Center for Consumer Research.

Take Moonlight, for example. With names such as Politix, Planet, Metro and City, RJR is tossing around cultural buzzwords to attract youthful smokers. The Politix package has a peace sign with the slogans "Join the Party" and "Lighten Up." Planet, launched as a Twentysomething competitor to the Native American-made American Spirit brand, boasts "No Additives - 100% Tobacco."

Fittingly, the offering of superficial political and environmental messages on cigarette boxes seems to cater to what has become a fleeting political concern among Generation Xers. Like bumper stickers, Moonlight boxes very well may become a quick-and-dirty way for youths to proclaim their political leanings.

It's a brilliant marketing technique. Big Tobacco, like all other large industries, are fully aware of how to romance youthful customers by appealing to psychological needs, such as autonomy, self-reliance, and independence. Key to capturing many young puffers are "microsmokes," such as RJR's Moonlight and Dave's by Philip Morris, both of which are being test-marketed in Seattle. Inspired by the microbrew craze, the shallow yet effective marketing messages of these two brands espouse a radical, anti-corporate spirit that resonates with young men and women.

Despite the obvious irony of Big Tobacco marketing microsmokes, the propaganda seems to be working. "The tobacco industry has a continuing interest in capturing the youth market, where virtually all smokers start on the road to life-long additions," said Richard Pollay, marketing professor at the University of British Columbia and curator of the History of Advertising Archives.

The Younger The Better

The transformation of cigarette advertising during the past half-decade certainly bears out Pollay's conclusion. World War II-era ads primarily featured men and women in their 30s-50s "enjoying" cigarettes. Since the 1970s, an accelerated trend has seen younger and younger people featured in ads.

Big Tobacco certainly didn't pursue hippies in the '60s or punkers in the '80s, but the industry sure is making a play for Twentysomething trendsetters of the '90s. And while cigarette ads may not picture tattooed, nose-pierced hipsters puffing on butts, RJR and other tobacco companies are reaching them another way: through a line of merchandising that strikes at the very heart of youth culture.

Big Tobacco certainly didn't pursue hippies in the '60s or punkers in the '80s, but the industry sure is making a play for Twentysomething trendsetters of the '90s. And while cigarette ads may not picture tattooed, nose-pierced hipsters puffing on butts, RJR and other tobacco companies are reaching them another way: through a line of merchandising that strikes at the very heart of youth culture.

Inserted in recent Stranger and Seattle Weekly editions was the "Camel Cash Groove Blender Mixers Guide." The glossy, full-color pamphlet offers Camel smokers the opportunity to buy shot glasses, playing cards, poker chips, trippy T-shirts, aviator jackets, even lava lamps emblazoned with the Camel logo.

Leaping onto the music bandwagon, Camel has produced compilation CDs called "Alternative," "True Blues," "The Best of Classic Rock," and "A Little Bit o' Country." They're even offering subscriptions to several Pop Culture magazines, including Spin, Interview, Ray Gun, US, and Rolling Stone.

Taking a page out of the beer industry's marketing strategy, Camel is giving away 500 trips to Las Vegas for its "Big Vegas Groove Blender" concert in late November. Curiously, no bands are listed; the pamphlet only says the entertainment will be "the newest of the new, the alternative to the alternative ..." (Sweepstakes entrants, beware: if you enter and you're under 21, you could be breaking law - apparently because Camel intends on sending free cigarettes to people who send in the entry form.)

What cannot be overlooked is the similarity of RJR's Twentysomething marketing campaign to the co-opting of youth culture by the corporate music, beer, fashion, and movie industries.

Creative, young entrepreneurs such as those who opened Moe's, Sit & Spin, and Kid Mohair may have initially intended to create fun places for people in their age and cultural groups to hang out, and maybe to make a few bucks along the way. But by accepting money from and joining forces with RJR to essentially become an ally of Big Tobacco, these and other local businesses are contributing to the selling out of youth culture to the highest bidder. And bids don't get much higher than those from the cigarette industry, which has a $6 billion annual marketing budget.

Whether Moonlight and Dave's go the way of O.K. Cola remains to be seen. The question remains: If hipsters saw through Coca-Cola's marketing campaign, why can't they see through RJR's?

Please see: Reader responses to this article.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the July/August, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.

On closer inspection, RJR's advertising blitz is much more than just a marketing campaign. The company is not merely selling cigarettes. It's selling a lifestyle. Just as makers of cars, beer, soft drinks, movies, fashion, and, of course, rock 'n' roll have endeavored to define what is "cool" to America's impressionable youth, RJR and other cigarette companies have finally recognized that their very survival depends on having a hand in shaping Pop Culture. And that's exactly what RJR is trying to do, right here in Seattle - the Barometer of Hip.

On closer inspection, RJR's advertising blitz is much more than just a marketing campaign. The company is not merely selling cigarettes. It's selling a lifestyle. Just as makers of cars, beer, soft drinks, movies, fashion, and, of course, rock 'n' roll have endeavored to define what is "cool" to America's impressionable youth, RJR and other cigarette companies have finally recognized that their very survival depends on having a hand in shaping Pop Culture. And that's exactly what RJR is trying to do, right here in Seattle - the Barometer of Hip.  One day in May, KBA rep Dennis Masel walked into Lux with a thick binder full of flashy, full-color ads, flyers and other promotional material. A handsome guy in his early 30s, his mission was to persuade Kender to throw a Camel-sponsored party - perhaps a barbecue or something with a motorcycle theme - if she would agree for seven months to sell only RJR cigarettes and deck the place out with Camel signs, displays, ashtrays, beverage napkins, matchbooks and the like. Masel said he'd pay up to $1,500 for the party and handle all the promotions, including (for some reason) advertising in Chicago and New York.

One day in May, KBA rep Dennis Masel walked into Lux with a thick binder full of flashy, full-color ads, flyers and other promotional material. A handsome guy in his early 30s, his mission was to persuade Kender to throw a Camel-sponsored party - perhaps a barbecue or something with a motorcycle theme - if she would agree for seven months to sell only RJR cigarettes and deck the place out with Camel signs, displays, ashtrays, beverage napkins, matchbooks and the like. Masel said he'd pay up to $1,500 for the party and handle all the promotions, including (for some reason) advertising in Chicago and New York.  Big Tobacco certainly didn't pursue hippies in the '60s or punkers in the '80s, but the industry sure is making a play for Twentysomething trendsetters of the '90s. And while cigarette ads may not picture tattooed, nose-pierced hipsters puffing on butts, RJR and other tobacco companies are reaching them another way: through a line of merchandising that strikes at the very heart of youth culture.

Big Tobacco certainly didn't pursue hippies in the '60s or punkers in the '80s, but the industry sure is making a play for Twentysomething trendsetters of the '90s. And while cigarette ads may not picture tattooed, nose-pierced hipsters puffing on butts, RJR and other tobacco companies are reaching them another way: through a line of merchandising that strikes at the very heart of youth culture.