Professional Sports for the Professional Class

In the game of stadium roulette, the taxpayers and fans are the losers.

by Nick Licata

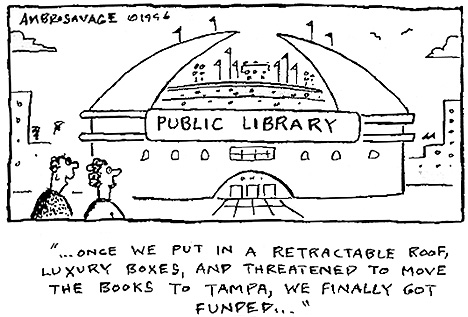

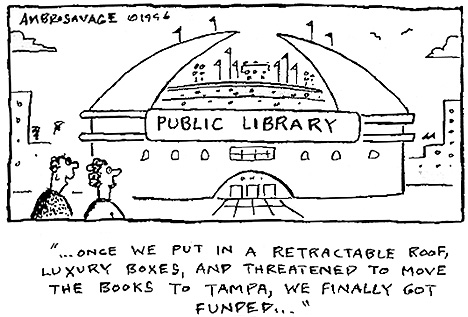

illustration by John Ambrosavage

Free Press contributors

Last year Seattle almost lost its professional baseball team, the Mariners. And as this article goes to press, its professional football team, the Seahawks, is making plans to nest elsewhere. Although the owners of the Mariners were anointed as good guys by the press while the Seahawks Ken Behring has been just about pilloried, they both played the same game: give me what I want or your team will be only a dream come next season. The same threats are echoing across the country as cities vie with each other in spending public funds to "save" or "lure" professional sports teams for their city.

Cities have been rushing to meet deadlines imposed upon them by teams threatening to leave if they don't get new and improved facilities. The Illinois Legislature literally turned back the clock at midnight by voting to build the $185 million Comiskey Park so the Chicago White Sox would not move to Florida. Similarly, in Cincinnati, public officials facing a midnight deadline agreed to raise the sales tax by 1 percent to build two new stadiums without a public vote to keep the Bengals from moving to Baltimore.

That's where the Cleveland Browns went after the Cleveland Indians successfully demanded and then got a new stadium, leaving the public coffers empty for the Browns when they wanted their new stadium. Which brings us to the Seattle Seahawks, who like the Browns saw their fellow municipal baseball team raid the local treasury first, leaving nothing for them. After the Kingdome's roof had been replaced the Seahawks wanted an additional $100 million in renovations. When the ballot measure failed and the state legislature refused to include money for Kingdome renovations, the vans rolled up and Behring proceeded to move the club office to Los Angeles.

That's where the Cleveland Browns went after the Cleveland Indians successfully demanded and then got a new stadium, leaving the public coffers empty for the Browns when they wanted their new stadium. Which brings us to the Seattle Seahawks, who like the Browns saw their fellow municipal baseball team raid the local treasury first, leaving nothing for them. After the Kingdome's roof had been replaced the Seahawks wanted an additional $100 million in renovations. When the ballot measure failed and the state legislature refused to include money for Kingdome renovations, the vans rolled up and Behring proceeded to move the club office to Los Angeles.

Follow the Bouncing Balls

These are examples of just a few local skirmishes that comprised the national war that has raged around the country among angry fans feeling rejected, frustrated municipalities being blackmailed, and money-conscious owners drawing fire. In 1995 alone, 38 other major league franchises were threatening to move unless they got a new arena or stadium. By the end of the year a record 5 NFL teams had moved.

Why all the movement? The answer isn't because professional teams have suddenly become greedy. Rather, club owners are following the dictates of a market place distorted through time by a continual infusion of public subsidies. If team A can get a new facility and attract higher attendance and obtain a greater profit, then they are more likely to be able to hire better players and win more games than team B which didn't have that public subsidy. So unless team B convinces the local public to dig into their pockets, they move to a community that will. The clubs have discovered that it is often more profitable to move to a new city because the new municipality will pick up a larger portion of their costs.

In addition, clubs have found that a new or renovated facility allows them to capture a new and most lucrative type of revenue stream: luxury boxes & club seats. Time ran a story on the phenomena in its July '95 issue with the heading, "Cities are winning and losing teams based on how many luxury boxes they can offer greedy owners."

Craig Simon, director of sports marketing for the Frankel & Co. consulting firm, provided the following quote, "Luxury boxes are critical these days. A stadium that doesn't have them is in danger of losing its team." The Raiders left Los Angeles for Oakland to get luxury boxes that the LA Coliseum promised but never provided. The boxes could net the Raiders an extra $7.6 million. But the Mariners could make twice that amount with the projected 78 luxury box suites and up to 6,000 club seats that the new promised stadium could accommodate. Meanwhile the general admission seats were shaved by 84 percent , leaving only 2,900.

What used to be a game that appealed to families is now marketed to an upscale clientele of business executives and professionals. As an example, Phoenix's new baseball stadium to be opened this season will have the entire second tier of its three tiered facility reserved for luxury boxes and full-season ticket holders. They get their own parking garage and wait-service at their seats.

Ironically it's the wage workers' taxes that build such facilities. Although Seattle's stadium financing scheme was an improvement over the one presented on the failed ballot, the general public still pays. And they may have to dig into their pockets again to "save" the Seahawks or to lure yet another football team to replace them. It's a never-ending story of professional sport teams claiming poverty.

The economics of professional sport teams is a conundrum to the public. The three prior owners of the Mariners have each claimed to be going broke. Yet when they sold this money losing team, each pocketed a receipt that ranged from 33% to 600% over their original purchase price.

How can teams that claim to be going bankrupt every year appreciate in value faster than the rate of inflation? The answer lies in the tax laws. When a team changes hands, Internal Revenue Service rules let the new owners depreciate what amounts to a big chunk of player contracts. As player salaries grow, so do the tax write-offs at sale time.

Club owners say that baseball players are being paid too much, pointing out that the average baseball salary doubled alone from '89 to '93 and is now over $1 million a year. However as a comparison of their salaries to the overall revenue of a team, the percentage that they make (just less than 60 percent of club revenue) compares favorably to what advertising agencies, law firms and consulting agencies pay their professional staff.

It's not that baseball players are greedy but that professional sport revenues have grown so much. For the past 90 years, prices paid for teams have doubled about every nine years, but the pace has accelerated-largely due to public subsidies flooding the market. Seattle has become just one more market swept away in this process.

Nick Licata is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the April/May, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.