REGIONAL WRITERS

IN REVIEW

|

by Ursula K. LeGuin Harper Collins, 1996, 207 pp., $22 |

Le Guin has become a master of all the literary tenses: realistic fiction that takes place in the possible past or the possible present; science fiction set in the possible, or sometimes impossible, future; fairy tales situated squarely in the impossible past; and myths that range dangerously across time and probability.

The impossible present, however, is particularly slippery. It flows into more styles and wears more names than any of the other literary tenses. The satiric 18th century travelogues "Candide" and "Gulliver's Travels" certainly take place in the impossible present. But by the next century, the impossible present had moved on to individual hallucinations in the stories of Edgar Allen Poe and Lewis Carroll.

Then in 1837 the impossible present became science as well, when the Russian mathematician, Nikolai Lobachevsky, published his historic paper "Imaginary Geometry," which describes a new, alternative geometry based on imaginary numbers. The square root of negative one can't exist. It is an imaginary number. And it proves to be quite useful.

The impossible present proves useful to 20th century writers as well: to Luigi Pirandello and his theater of the absurd, to Franz Kafka and his prophetic surrealism, to Jorge Luis Borges and his urbane incantations. Now at the end of the millennium it is being stretched in wondrously different directions by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, Thomas Pynchon, and Ursula Le Guin.

In the opening story of Unlocking the Air, Le Guin makes a card deck of five people: Stephen, Ann, Ella, Todd and Marie, and plays out all the possible hands. Stephen is Ann's father; Ella is his new wife; Marie is his ex and Ann's mother; Todd is Ella's retarded son; and Ann is pregnant. But wait, Todd is Ann's retarded brother; Stephen is their father; Ella is their mother; Marie is Stephen's new wife; and Ann is pregnant. Six more times Le Guin shuffles and deals the characters across the spectrum of possible roles and loves. Each time she poignantly draws them in their pleasures and pains, capturing, for a moment, love itself in fiction, just as Claude Monet captured, for a moment, light itself in his painting series of haystacks and cathedrals.

In Le Guin's hands the impossible present is funny and illuminating. The story "Ether, OR" is about a town of that name, a name that's a joke and a choice, a town that up and moves itself all over the state. "Ether itself never has been in the Cascades, to my knowledge. Fairly often you can see them to the west of it, though usually it's west of them, and often west of the Coast Range in the timber or the dairy country, sometimes right on the sea." The Ether townspeople are confused, not by their town's dislocations, those they've gotten used to, but by life's dislocations. "They're all strange, men are," Edna thinks to herself; and she should know, she's had most men in town. "I guess if I understood them I wouldn't find them so interesting." On the emotional other side of town, Thomas says to himself, "When I first came here I used to take some interest in a woman [namely Edna], but it is my belief that in the long run a man does better not to. A woman is a worse hindrance to a man than anything else, even the Government."

Decades younger and just entering the human confusion, Starra is practicing love so she can be a great lover. She is falling in love with Lt. Worf, the Klingon on TV, and wondering about loving an alien, about loving a black man in a lily-white town, about loving a character who is actually a real person living in an entirely different universe.

Le Guin also creates ominous impossible presents, like "In the Drought," where one day all the same-sex couples in town find their water faucets run "a thick, strong, bright-red rush," while their neighbors' water stays clear and drinkable. Living in Oregon and writing about the West, Le Guin knows how this can happen.

"Unlocking the Air," the title story, begins by saying, "This is a fairy tale," but it is a realistic history too, of a central European nation, and a square in its capital, and the stones of that square that have worn blood and been worn by bare feet, boots, tank treads, and the 55,000 people that gather in the snow at night to end an evil enchantment on a Thursday in 1989. Le Guin prepared the ground for this story ten years earlier in her historical novel Malafrena, which invented this country of Orsinia as it passed through the time of liberal revolutions in the 19th century. Malafrena was full of important ideas, but was only an average novel. Yet when what was unimaginable happened once again in Berlin and humanity overcame the wall, Le Guin was ready to write a definitive story of that moment-how the air of earth itself was once again unlocked.

With this collection Le Guin has catapulted over the boundaries that separate contemporary fiction into different genres. She is a wise wizard spinning and mixing realism, fairy tales and impossibilities. One of her stories might be about anything: a woman on the bus, Sleeping Beauty, a dying beetle, an abortion, a naked poet in a forest pool, a girl who never stops growing. The great range of her ability fills her fiction with surprise. Everything might happen, and more.

|

A Memoir of Seattle in the Sixties by Walt Crowley University of Washington Press, 1995. 352 p/16 p of illus. |

|

Apathy and Action on the American Campus by Paul Rogat Loeb Rutgers University Press, 1994, 460 p. |

Though I was still learning how to tie my shoes around the time heads were getting bashed in at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, I feel more affinity, more connection, and, well, more loyalty to the Youth Movements of the 1960s and '70s than those of the '80s and '90s.

Turning the pages of Walt Crowley's Rites of Passage and Paul Rogat Loeb's Generation at the Crossroads , I found no reason to change directions. I wanted to find one, but I didn't.

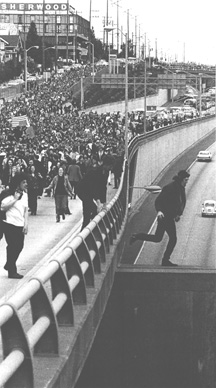

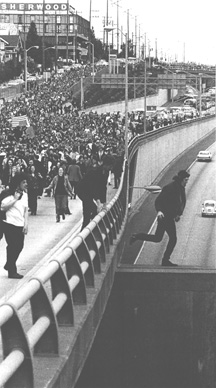

Both are marvelous works. With heart and humor, Crowley chronicles political and social upheaval in the Emerald City through the words and images of the Helix , a quintessential underground-lefty rag that published 125 issues from March 1967 to June 1970. A writer and illustrator with the Helix (and a 1968 state Legislature candidate from the Peace and Freedom Party), Crowley drops the reader squarely into the middle of police riots and thronging rallies without the ideological fanaticism that tarnishes many such histories. It's unalienating storytelling at its finest.

Loeb, a prolific writer and tireless lecturer whose past works include Nuclear Culture and Hope in Hard Times , presents a relentlessly enlightening analysis of the current state of political expression on our country's college campuses. The effort is the product of six years' worth of in-depth discussions Loeb undertook with hundreds of students from Brown to Berkeley.

While he ends on a note of tempered optimism (". . . we should be heartened by renewed student involvement. . . we honor their resurgent commitment. . ."), Loeb opens his book with an excruciating portrayal of a hopelessly self-absorbed student-body politic that is almost too painful to read.

Young adults Loeb encountered left no stone unturned in their search of excuses to disregard matters political. Ignorance: "We need to know so much just to understand what people are talking about." Intimidation: "I feel life I'd have to take on the whole world." Individualism: "The world would be lots better off if people attended to their own work." Resignation: "We've been taught that God is in control, our leaders are in control, and there's nothing we can do." Peer pressure: "It might separate me from the right kinds of friends, the ones I'm supposed to hang around with." Insecurity: "If I make an action, then I'm responsible for it. I'm risking my comfort zone." Futility: "I look around, and I feel I can't do anything about it." Selfishness: "I want to be able to say, 'Buddy, buzz off. This is mine. This is what I've paid for.'" Greed: "I came to college so I could be rich in the future."

|

|

|

Dubious assessments, to be sure, from a generation of youths who, according to public-opinion surveys, know more about ex-President Bush's dog, Millie, than such recent events like the tearing down of the Berlin Wall, the Tiananmen Square massacre, or the events leading up to the Gulf War.

I suppose what irked me the most were students' blind assertions that '60s and '70s activists "sold out" later in life. "Now they're all a bunch of yuppies. . . They talked a good line when they were young. . . In the '60s those people were pushing peace. Now they're not doing anything."

For as much that Loeb explores young people's misconceptions of the '60s, Crowley shoots these distortions out of the sky - particularly on the great myth of the '60s "sell-outs." Crowley traces the formative years of many Seattleites who, instead of selling out, bought into the system.

"Buy-in" Jim McDermott, for example, in 1967 helped start the Open Door Clinic, a place where people strung out on PCP and other hard drugs could get help. Today, McDermott is using his seat in Congress to crusade for a universal, single-payer health care system.

Then there's William Dwyer, who, as an ACLU attorney in the late '60s, represented Black Panthers and defended a bookstore clerk arrested for selling the Kama Sutra. Today Dwyer is a progressive-minded federal judge whose rulings included a landmark decision protecting the spotted owl.

Larry Gossett cut his political teeth as a co-founder of the UW Black Student Union and a courageous dissenter who went to jail for protesting the expulsion of a classmate from Franklin High School. Many years of community activism culminated in his recent election to the Metropolitan King County Council.

During the late '60s, Lembhard Howell helped force local unions to hire African-American apprentices, and represented the family of a black Viet Nam veteran shot to death by a Seattle police officer. Today Howell, who continues to battle police brutality, is one of the nation's most celebrated civil rights attorneys.

Of course, a symbol of political commitment himself is Crowley, who, as a researcher and writer has helped champion dozens of progressive political and environmental causes during the past 25 years. (Plus, he helped spare the Blue Moon Tavern from the wrecking ball.)

Many local institutions also grew out of the '60s counterculture, including Bumbershoot, the UW Experimental College, and the Country Doctor clinic on Capitol Hill.

If the '60s taught us anything, it's that making excuses for indifference is nothing more than an admission of personal weakness. Youth is the time for experimentalism and risk-taking. Sadly, so very many of today's college-aged men and women have chosen to abandon political challenges and opportunities. Now, who are the real sell-outs?

|

|

|

|

|