BC Natives Want Trees, Not Treaties

The governments of Canada and British Columbia refuse to own up to the promises of a colonial king

By Matt Robesch

The Free Press

To find a legitimate agreement made between the Native peoples of Canada and a colonial-era person of any kind, one would have to search among documents over 230 years old. There is, in fact, only one such document - The Royal Proclamation of 1763. Handed down by King George III in an era when the "New" World was being divided up by European colonial forces, this document was somewhat ahead of its time.

This proclamation, among other things, details at great length how British subjects anywhere were to treat indigenous people, particularly those of North America. A key portion of it states: "The several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom we are connected, and who live under our protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the possession of such parts of our dominions and territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their hunting grounds..."

The gist of this paragraph and the rest of the proclamation is clear. If you didn't buy the land from the natives, and they didn't give it to you . . . have some respect and stop stealing it from them!

Of course, Canada is no longer a British colony and may no longer be held to centuries-old British promises. However, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the "rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763."

Canada has, for the most part, granted greater autonomy to their native populations than has the United States. Compared to the US's 19th century policy of relocating or murdering Indians, Canada's treatment of its native peoples gives the impression that it let them live virtually unmolested.

But appearances can be deceiving, especially where capitalism is concerned. The profit motive has brought Canadian federal and provincial officials in direct conflict with sovereign Native Nations numerous times over the centuries. These clashes escalated in the 1990s, with the celebrated struggle over Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island, where native groups and environmentalists resisted clearcutting of ancient forests. Last year marked a series of actions designed to assert traditional rights to ancestral lands. Shuswap natives refused to leave a ceremonial Sundance site at Gustafsen Lake, BC last summer in order to resist encroachment by ranchers on their lands.

Also in 1995, the Little Shuswap, Adams Lake, and Neskonlith bands blockaded the site of an RV park set on top of a native burial ground. The Nanoose First Nation in Vancouver blocked a condominium development after developers removed 147 skeletons from a burial ground said to contain over 1000 remains - the largest native burial ground in British Columbia. The Upper Nicola band blockaded BC's largest cattle ranch in protest of violations of fishing rights and environmental despoilation caused by the ranch. Current struggles are raging now on King Island and along the coast of British Columbia.

These standoffs are markers of a growing native rights movement which rejects codified treaties which parcel out lands to incorporated tribes. The movement marks the divide between tribes willing to cooperate with the current treaty-writing process instigated by the BC government, and those unwilling to circumscribe their sovereignty in writing. According to Kim Goldberg, writing in the December issue of Canadian Dimension, "The split between hereditary and elected leadership is the leading edge of a much deeper divide separating traditional, Earth-centred natives from those more fully absorbed into the capitalist value system, and whose economic development plans can best be met through the current treaty process." The debate always boils down to one crucial question: Whose land is this?

Who Owns the Forests?

Who Owns the Forests?

North of Clayoquot Sound, on King Island, and on mainland British Columbia, stands the largest surviving portion of an old growth forest which once stretched from Northern California to the Alaska Panhandle. This is the Great Coastal Forest. There are no roads for more than 12,000 square-acres. According to Forest Action Network (FAN), this chunk of forest "is the only remnant of true wilderness large enough to support the biodiversity required to reforest the devastated Cascadian ecosystem."

This forest is also the traditional land of the Nuxalk Nation. Ed Moody is a hereditary chief of the Nuxalkmc (Nuxalk People). "We have a story of First Woman sitting upon the earth at Ista [on King Island in BC], the lady that was descended came down with a pearl blanket. There is a song from Ista, a woman's song, and a woman's dance with sweeping arms to clear the way for our spirits. We have recognized King Island as one of our sacred sites, we still hunt, trap and gather medicines there." One type of tree in this forest is said to hold the cure for tuberculosis.

International law specifies that governments must work out treaties with the indigenous peoples within their borders. "In BC there are many sovereign nations that have never signed a treaty with the government," says David Goldman, a member of the Seattle chapter of the Forest Action Network (FAN).

The British Columbia Treaty Commission is dealing with the lack of treaties and unceded lands within their province by engaging indigenous nations in treaty and land claims discussions. But many tribal members reject the notion of a treaty. They argue the commission is trying to construct one "blanket treaty" that will automatically apply to all nations.

"The government is fooling a lot of Indian people today," says Nuxalk Chief Ed Moody. "They say we have to settle our land claims through the BC Treaty Commission. The Commission is set up by the white government to wipe out all our rights as Nuxalk People. We don't have to sign treaties with anyone.

"There has never been any treaty, agreement or consented arrangement made with us and them [BC or Canada]. Therefore, we know, through international law, that these two governments are practicing their jurisdiction illegally on our land."

The March of Greed

Despite an alleged adherence to the Royal Proclamation, and despite the fact the Nuxalk Nation has not ceded as much as one tree to any government, last summer the BC Ministry of Forests granted permits to several logging companies, giving them the green light to start clear-cutting in the area.

To the West, the forest is being logged by MacMillan Bloedel (Mac-Blo). To the North it is logged by Western Forest Products and Dean Channel. To the South and East the logging is being done by International Forest Products (Interfor).

The BC government issues logging permits to numerous companies large and small. Interfor, which began blasting roads through the forest last June, buys up many of these small companies, absorbing them into their clear-cutting juggernaut. In the Nuxalk situation, the company claims it made all logging arrangements with the Heiltsuk Nation, an indigenous neighbor of the Nuxalk. The Nuxalkmc agree the two tribes share the area, but insist no arrangements were ever made between itself and any political body or corporation.

Mac-Blo has financial ties to the BC government. A recent issue of Threshold, the newsletter of the Student Environmental Action Coalition asserts, "The British Columbia government is the major shareholder of Mac-Blo so each time they sell a permit to Mac-Blo they are making enormous profit. Each logging town that grows and then dies makes a small amount of money, but the BC government profits every time."

Mac-Blo has a reputation for destructive logging practices. Protesters dumped 800 pounds of horse manure on the steps outside the company's recent annual general meeting, chanting "Same old shit!" Last fall The New York Times severed relations with Mac-Blo, expressing concern over how the company conducts its business.

Logging companies are not the only entities applying economic pressure that is pro-plunder. Mining companies are also looking upon the Great Coastal Forest with dollar signs in their eyes. They share an interest in clear-cutting and logging roads, for they cannot move in and dig their mines until the trees are all gone.

Temporarily Halted

Ista (also known as Fogg Creek), the landing at King Island, is where members of the Nuxalk and Heiltsuk Nations and a small group of activists took a symbolic stand. One night in early September of 1995, the activists constructed a roadblock and set up platforms for sleeping 80 feet up in the trees. The next morning Interfor work crews reporting for duty were told to leave. On the second day the workers returned again but were not allowed off of their boats, except to gather personal gear from their trucks, which remained on the island.

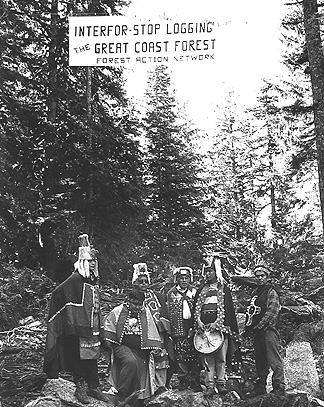

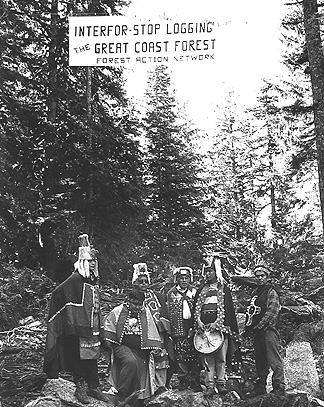

Nuxalk traditionalists stand in an area cleared for an

Interfor logging road at Ista in September of 1995.

Ista is the Nuxalk name for Fogg Creek, King Island,

along the mid-coast of British Columbia.

(photo by Kim Wolston)

|

The protest lasted just over three weeks. During the first week Interfor arrived on the island with an injunction to halt the blockade, threatening to charge the Nuxalkmc and other protesters with trespassing. The blockaders informed everyone present that the company reps were the true trespassers and promptly set fire to all copies of the injunction. This, evidently drew the ire of Canadian officials, as detailed this Fall in Earth First! Journal:

The burning of the injunction led to an angry response on national television

from the Attorney General and the dispatch of several Royal Canadian Mounted

Police (RCMP) officers to Fogg Creek, to remind the blockaders of the gravity

of their offenses and the potential consequences. Upon their arrival the RCMP

officers were met by Nuxalk and Heiltsuk traditionalists who went beyond their

long-standing disputes over claims to this area to stand together in asserting

sovereignty. In what may be an unprecedented gesture of recognition of that

sovereignty, the RCMP removed their weapons at the request of the tradition-

alists and left them behind in their boat before setting foot on Ista.

At the height of the stand-off, 60 people were camping at Ista in protest of the logging operations. The group erected a smokehouse, using trees felled by loggers, to begin processing fish at the site. Finally BC officials decided enough was enough. Interfor employees arrived with a platoon of RCMP, boats and helicopters. Twenty-two people were arrested, the smokehouse was smashed and the company picked up where it had left off - blasting roads through the forest.

Put On Trial

At the BC Supreme Court in Vancouver, all of those arrested who signed a promise not to return to the site were released. Three Nuxalk hereditary chiefs and a protester from the Ojibway tribe refused to sign on the grounds that to have done so would have been to acknowledge BC's claim of jurisdiction over them and the land. Tribal chiefs Lawrence Pootlass, Ed Moody, and Charlie Nelson spent the next 23 days in jail. When Chief Pootlass' wife fell ill with pneumonia, he was allowed to go to her side only after signing a note promising he would appear in court December 4. Amelia Pootlass died later that same day. Wanting to be with their elder during his time of mourning, Moody and Nelson signed similar promises and were released.

On December 5, Paul Hundel, lawyer for the Ista defenders, challenged Supreme Court Justice Smith to prove the court's jurisdiction over the land and tribe by providing official papers documenting a Nuxalk secession of all rights and claims. The court was unable to comply. Regardless, the Justice refused to recognize the tribe's sovereignty. In response, the Nuxalk chiefs and 19 other defendants walked out of the courtroom. Hereditary Chief Moody stated that the Nuxalkmc, "have exhausted all domestic efforts.. our only recourse is international opinion."

Justice Smith refused to issue arrest warrants for the defendants opting instead to reschedule the trial. The next act in this drama occured on January 22, 1996 when court reconvened. None of the 20-plus defendants appeared at court. The court issued warrants but the RCMP could not locate anyone of the accused. At press time, the defendants were in hiding.

What Lies Ahead...

Recent bad weather has kept Interfor from making much progress into the forest, but the company plans to continue logging on King Island in February. This relentless foray into one of the last stands of old growth forest left in North America has garnered worldwide attention.

According to FAN's David Goldman, during the blockade, "There were rallies all over the world: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Pittsburgh, three cities in Germany, and England." These protests are likely to continue and grow in scope as the trees continue to fall.

John Quigley, also a FAN spokesperson, adds "The international environmental movement sees this as the sequel to Clayoquot Sound." Two years ago international media focused on BC when another major logging battle took place over a considerably smaller forest on Vancouver Island. "We're fighting for the last large piece of self-sustaining coastal temperate rainforest and it's just not going to stop . . . so it would serve Interfor well to begin preparing to shut down operations," said Quigley.

The Nuxalk fight to save the Great Coastal Rainforest goes beyond the issue of one native nation's sovereignty. It concerns everyone in the region, tribal or not.

Clear-cutting practices ruin wildlife habitats, forcing animals to flee or be killed. Without trees to absorb water and hold the ground in place, hillsides slide into rivers. Silt and mud build-ups in rivers cause flooding which, in turn, cuts off salmon runs. When salmon runs die, the livelihoods of fisherman up and down the West Coast are affected. When flooding occurs, the delicate chain which exists in this large undisturbed watershed could eventually reach farming communities and, finally, those who are dependent upon the farms for food. As the forests continue to fall, even distant city dwellers will eventually feel it.

The BC and Canadian governments appear ready to allow profiteering to prevail over environmental common sense. Thankfully, the various Canadian governing bodies, in all the years since the colonial period, never drew up official treaties with many of the native nations within their borders. The overlooked sovereignty of one native nation may well save this important forest from becoming devastated in the name of toilet paper, newsprint and, above all, greed.

This story was updated in the July/August 1996 issue of Washington Free Press. Please see:

"Nuxalk Sovereignty Ignored"

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the February/March, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.

Who Owns the Forests?

Who Owns the Forests?