FIRST WORD

FIRST WORD

IDEAS THAT

CUT THROUGH

THE BS

House of Bill

The lights go on, but is anybody home?

By Eric Nelson

The Free Press

Every mogul must build a mansion, and William H. Gates III is no exception. We've all heard about the $30 to $50 million price tag, the 40,000-square-feet, dining for 100, an underground 20-car parking garage, the underwater music system in the pool, and electronic pins that track occupants around the house. We've snickered over rumors of high-priced change-orders as the now-married Gates converts a tricked-out bachelor pad into a "family home." Clearly, Gates has not taken E.F. Schumacher's Small is Beautiful to heart.

But Gates is building more than a house. He is constructing an image and

placing an identity on his wealth. The House of Bill is the first chance

us outsiders get to probe the mind of the man; the first public expression

of Bill-culture. And Gates himself has helped us in this endeavor by

promoting it as the house of the future in The Road Ahead, his

paean to a techno-utopia.

Future Lord Bill

Almost a hundred years ago, the social theorist Thorstein Veblen examined

the practice of "conspicuous consumption" and "waste." Ostentatious

displays of wealth, Veblen noted, are the products of a "predatory

culture" where moneyed superiors lord over their inferiors. As they schlep

across the 520 bridge to the software mines every morning, the Microserfs

can take this to heart as construction cranes tower above Lord Bill's

lakeside property.

In this sense, Bill Gates "lords" over us just as surely as his pecuniary

predecessors -- the Vanderbilts, J.P. Morgan, and William Randolph Hearst

-- lorded over the 19th century masses with their own great temples of

marble, stone and ego. Bill Gates has joined the tycoon class.

As an added twist, Gates has coordinated the gradual unveiling of his

wealth display with a well-orchestrated marketing blitz to convey his

vision of the future. However, in so far as domestic culture is concerned,

Bill Gates' "Road Ahead" has been well-traveled. Take a look at Seattle's

1962 World's Fair, which featured a Space Age theme house of the future.

According to UW historian John Findlay, who recounts the fair in his book,

Magic Lands, "The shape, color, and lighting of the house could all

be changed quickly in order to meet shifting preferences, and the kitchen

seemed 'a miracle of push-button efficiency.'" In retrospect, the 1962

fair was a middle-class vision of compliant housewives, maximized

efficiency and the masculine thrust of the Space Needle into the future.

"At bottom," Findlay notes, "the fair's version of the future was not very

imaginative; it seldom took into account the possibility of fundamental

social and cultural changes."

Likewise, Gates' "vision" is disappointingly shallow. Frankly, the

Road Ahead reads as if Bill is beginning to believe his own

marketing bullshit.

Gates' house will be a palace of gadgetry. He writes, "When it's dark

outside, the (electronic tracking) pin will cause a moving zone of light

to accompany you through the house. Unoccupied rooms will be unlit." You

get the idea, the information age means we can't be bothered to use light

switches.

According to Gates, in the future your wallet PC will instantly tell you

the location of the nearest Chinese restaurant, and later he explains how

we will pay for things (presumably all those Chinese dinners) with an

electronic debit card. Now that's progress!

Computer futurist Paul Saffo of the Institute of the Future noted recently

in the Washington Post that, "If this really reflects Mr. Gates'

vision of the future, then his vision can only be summarized as one of the

bland leading the bland."

Money buys many things, but it has obviously not provided Bill with much

perspective. Bill does not realize that many people are still concerned

about a daily bowl of rice and have yet to go "on-line" for a diet of

"electronic efficiency."

Brother Bill?

Whether Gates really believes in this future or not, there's something

creepy about a guy willing to incorporate the dystopian aura of pin

numbers, data banks, and electronic surveillance into his own home.

Gates achieves a striking effect with his electronic tracking pins. He

writes: "The electronic pin you wear will tell the house who and where you

are, and the house will use this information to try to meet and even

anticipate your needs -- all as unobtrusively as possible."

"Someday, instead of needing the pin, it might be possible to have a

camera system with visual-recognition capabilities, but that's beyond

current technology," Gates notes. Don't swipe the towels at this house,

Brother Bill is watching.

Sound familiar? "The telescreen received and transmitted simultaneously.

Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would

be picked up by it; moreover, so long as he remained within the field of

vision which the metal plaque commanded, he could be seen as well as

heard." (From the opening pages of Orwell's 1984.)

The pins also illustrate a key theme in tycoon behavior: control. Gates

and William Randolph Hearst are control freaks of a feather. At Hearst's

epic San Simeon castle overlooking the Big Sur coast, guests could not

drink in their rooms and had to wear costumes to a nightly procession lead

by the publishing magnate and his mistress. Hearst maintained strict

control on access. Nobody got by the gate without his approval.

In his book, Gates pointedly dismisses any similarity between San Simeon

and his house. But like Hearst, he seeks the immediate: news, visual

entertainment, or information on the whereabouts of his guests.

Patron of Virtual Art

Like all rich people, Gates is expected to be a patron of the arts.

Traditionally, European nobility supported the arts through stipends and

acquisitions. The American nouveau-riche just acquired, but with a vengeance.

Historian Stewart Holbrook, who detailed the rise and fall of the robber

barons and tycoons in his 1953 classic, The Age of Moguls,

described the Vanderbilt mansion as a mish-mash of treasures:

"The new impulse turned out to be glorious hash of styles and periods from

much of the known world -- French tapestries, Florentine doors, African

marbles, English china, Dutch old masters. These were mingled happily with

Oriental magnificence..."

Bill has proven himself more discriminating.

For instance, Gates indulged himself to the tune of $30.8 million for the

Leonardo DaVinci manuscript known as "Codex Leicester." (When

industrialist Armand Hammer owned it, he dubbed it "Codex Hammer.") But

this acquisition, representing a fraction of Gates' $13 billion in paper

wealth, is an investment in symbolism. By aligning his image with

DaVinci's, Gates casts himself as a renaissance man and seeks to enter the

pantheon of great thinkers and tinkerers. "DaVinci, Jefferson, Edison,

...Gates."

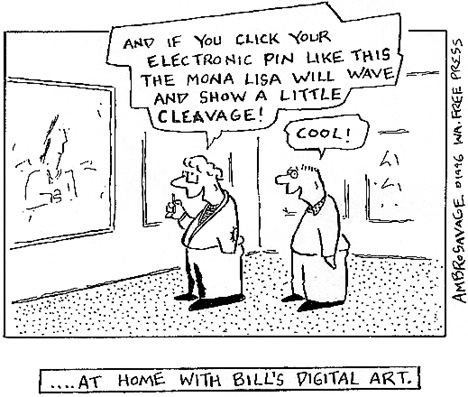

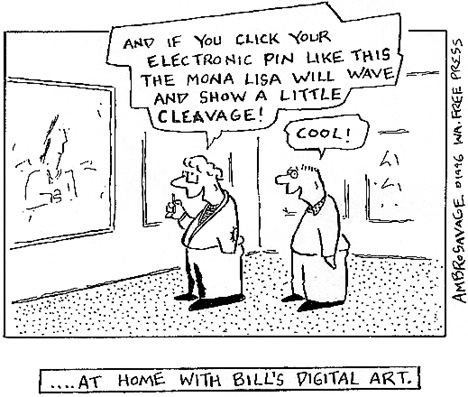

But Gates' experimentation with virtual art in his own house -- really a

test market for selling his licensed stock of images into your house --

reveals that he follows in the footsteps of another great inventor and

marketer, Henry Ford.

Ford was a new kind of mogul who scorned art (and history for that

matter.) Ford's middle class sensibilities prevented him from conspicuous

consumption of art. But Ford knew a good idea when he saw one and refined

mass production into an art.

As a "Fordist", Gates is concerned with product, distribution, and mass

consumption. In his house, high resolution video screens mean that "your"

art will follow you via your electronic pin as you move about the house.

Tired of your unruly, chaotic Jackson Pollock day? Change it to a more

peaceful French Impressionist day. Art becomes the object of immediate and

coldly technical gratification. In Bill's house, empty signifiers replace

the real thing.

Environmental Waste

Like the arts, Bill's house confuses the real environment with the

imagined. Moreover, Bill does not tread lightly with his massively

wasteful house. He pays lip service to environmental harmony, but there

appears to be no effort at solar technology or energy efficiency. The

house faces west to the sunset, not south to the sun.

Bill writes, "A small estuary, to be fed with groundwater from the hill

behind the house, is planned. We'll seed the estuary with sea-run

cutthroat trout, and I'm told to expect river otters." Otters, eh? Let's

hope they don't have to wear electronic pins too.

The upshot of all this is that until now Bill Gates has been a cypher to

the public. Now, through his house, we know him as we know Microsoft.

Both Gates and Microsoft have taken some heat for "dominating" the

personal computer industry. Conservative prophet of profit George Gilder,

writing in the Dec. 4, 1995 issue of Forbes, says we've got Gates all wrong:

"Blinded by the robber baron image assigned in U.S. history courses to the

heroic builders of American capitalism, many critics see Bill Gates as a

menacing monopolist. They mistake for greed the gargantuan tenacity of

Microsoft as it struggles to assure the compatibility of its standard..."

The fact remains, Bill's business and Chez Bill share some unsettling

characteristics: they are both big, unfriendly, sometimes threatening, and

mostly concerned with image over substance. The fact that Gates chooses to

live in the same way he conducts business is hardly surprising, but

certainly disconcerting.

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the February/March, 1996 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1996 WFP Collective, Inc.