Ft. Lewis only logs about 15 percent of the standing timber per acre when it thins its forests.

(photo by Patrick Kylen-Mitchell)

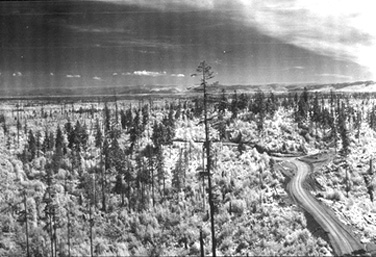

"This was all logged in January of 1995," forester Jim Rhode says, while walking in a steady rain and pointing to a stand of mature second growth forest beside a meandering gravel road in the middle of Fort. Lewis. There are no clearcuts, no big piles of slash, no fresh and muddy paths bulldozed into the woods. In fact, it doesn't look much different than areas on the Army base south of Tacoma that haven't been logged for 60 years.

As we walk back into the dripping forest, we start to notice a few stumps. They don't really stand out, as the tannish pink that marks the top of freshly cut Douglas Fir stumps has already weathered to muted grays and browns. Many of the stumps are already disappearing beneath the thriving plants of the forest floor. The soil shows no evidence of trees being dragged out to the road. If the logging left any scars on the landscape, they have disappeared less than a year later.

Welcome to forestry, Army-style.

While the timber battles have been raging in the Pacific Northwest's public and industrial forests, Ft. Lewis has quietly been running a forestry program that operates outside the political and economic pressure that drives the Forest Service and large commercial timber companies.

Much of what is now Ft. Lewis was clear-cut in the 1930s and 1940s, so most of the trees on the base are second growth that is at least 60 years old. When the base was established in the 1940s, the military decided it wanted to maintain a closed-canopy forest for training maneuvers, which essentially eliminated clearcutting as a forestry option. Ironically, this focus on military uses of the forest has fostered a unique - and thriving - selective logging program.

"The primary purpose of Ft. Lewis is for military training. That's what it's here for," explains Rhode, a civilian forester who has been working at the base since 1975. "We don't look at our forestry program as something that has some sort of priority, because it doesn't."

In spite of this, Ft. Lewis has put up some pretty impressive timber production statistics. The entire base covers around 87,000 acres, with 55,000 acres now covered in forest and 42,000 acres currently managed for timber production. When Ft. Lewis first inventoried its forests in 1965, the base harbored 426 million board feet of standing timber. In 1989, two inventories put the base's standing timber volume at close to 1 billion board feet. Over that time, from 1965 to 1989, Ft. Lewis harvested over 350 million board feet of timber, or close to the amount of timber that was there at the time of the first inventory.

"In other words," says Rhode, "we've taken out almost as much as we had to start with in 1965 and yet we've still managed to double what's out there now."

While the base's annual timber production - 10 to 11 million board feet - is just a drop in the bucket of Northwest timber harvests, the program is profitable and the value of the base's standing timber increases every year. In fiscal year 1995, Ft. Lewis grossed approximately $2.5 million dollars from its timber sales. Three counties - Clark, Pierce and Thurston - receive 40 percent of the net gross (the amount left after expenses are subtracted) on timber sales at Ft. Lewis .

Not only has Ft. Lewis doubled its standing timber volume while prodcuing a steady supply of lumber, it has also maintained critical wildlife habitat and a variety of rare ecosystems that have virtually been eliminated from the rest of Puget Sound.

"In the Douglas Fir zone, Ft. Lewis is unique," says Roy Keene, a forestry consultant and the former executive director of the Oregon-based Public Forestry Foundation. "There are no large forests the size of Ft. Lewis that can make the claims over the last 30 years that they can. Period."

Keene has worked with Ft. Lewis in helping to draw up harvest plans and says he's walked "just about every acre" of forest on the base. He claims that while Ft. Lewis has doubled its volume of standing timber per acre over a 30-year period, the Forest Service has lost from 20 to 30 percent of its timber volume in Northwest forests over the same period.

"Most of the federal agencies are very good at removing trees," says Keene, "but not very skilled at growing them. Ft. Lewis, by contrast, is very skilled at growing trees through a system of thinnings and partial removals. It takes timber to grow timber."

In the two decades since, in which battles over old growth forests and loss of wildlife habitat radically reduced the annual harvests on public lands and focused attention on harmful forestry practices on private lands, Ft. Lewis's logging program has quietly evolved into a model of sustainable forestry.

"Our program has always been based primarily on individual tree selection and periodic entry into the stands," says Rhode. "Now we're thinking more along the lines of ecosystem management."

Although the base is heavily forested, many of the timber stands are now in a "stem exclusion" stage, which is characterized by a closed canopy, few trees larger than 8 to 10 inches in diameter, scant understory vegetation, and very little natural regeneration of shade intolerant Douglas Fir due to a lack of sunlight on the forest floor.

Trees that don't keep up get very little sunlight and are "excluded" and die. This type of forest is typical of dense second growth forests that grow back in clear-cuts and is believed by some foresters to be the poorest in terms of wildlife habitat because there are few large trees that are homes to animals and fungi, and little understory vegetation for deer and elk to browse.

With maintaining and improving wildlife habitat now a primary goal at Ft. Lewis, foresters are working to break up the even-aged character of the base's second growth timber stands. By helping the forests to progress more quickly into a "late successional"or old growth stage, the base's foresters hope to create a healthier and more diverse forest.

Rhode employs two types of harvests, depending on the condition of the stand, to try and open the forest up and allow more sunlight into the understory. In one method, called "uniform density thinning," trees are selectively logged evenly across a timber stand.

In the second method, called "variable density thinning," tree removals are more clustered, creating holes in the forest canopy. The same amount of timber is taken out with both methods - about 15 percent of the standing timber per acre - but variable density leaves the forest with more of a patchy character.

Creating these open areas provides shade intolerant Douglas Fir seedlings with a better chance to get started, and speeds the growth of young trees that were once below the forest canopy and saw little sunlight.

In 1990, Ft. Lewis was designated as critical habitat for the northern spotted owl. Although no spotted owls have ever been found on the base, scientists believe it could be a critical "stepping-stone" between owl habitat in the Cascades and habitat in the Olympic Peninsula. Because of this designation, Ft. Lewis has worked closely with wildlife biologists and the state Department of Fish and Wildlife to assess any planned timber sales.

Although Rhode says he has his doubts about the ability of spotted owls to fly across miles of urban and suburban development to get to the base, and says that nobody knows if spotted owls ever lived in what is now Ft. Lewis, he says that the base's forests are being managed with the owl in mind.

"We're trying to maintain not only the forests themselves," he says, "but also trying to actually create a diversity of species and diversity of structure and all of the things that might be important from the standpoint of the owl."

For example, five years ago foresters at Ft. Lewis decided to stop removing dead wood from the forests during logging operations. "In terms of a healthy ecosystem," says Rhode, "we need coarse woody debris out there." Snags and downed trees provide vital wildlife habitat and are a key component of old growth forests.

In addition, Ft. Lewis no longer allows loggers to take trees that have to be cut down when putting in a road to access a timber stand. They are now required to drag them back from the road, into the woods. In this way, loggers are encouraged to put in access roads that do the least amount of damage to the stand.

"If (loggers) can say they need the stuff cut and then they can haul it out on a truck, then that's kind of an incentive for them to say they need this to come out of here," explains Rhode. "So by saying they're not getting it even if they cut it, it's kind of like 'Well, do I really need to cut this tree down?' "

In November of this year, Ft. Lewis initiated a certification program for all loggers who wish to work at Ft. Lewis. The course will educate loggers about the above-mentioned policies, as well as the base's desire that loggers keep an eye out for young Douglas Firs when deciding which direction to drop a tree. "It's kind of getting the loggers in on the reasoning behind what we're doing out here," he explains. "It's a learning process and they start to catch on."

Selective forestry can pose a lot of problems in the woods for loggers not used to this method of forestry, as they can't go in and simply cut down everything like in a clearcut. "We've got trees that we want to remain out there," says Rhode. "If we're talking about growing these different sizes of trees and we're busy dropping other trees on top of them and just smashing them up, then we're kind of defeating our purpose."

Although some loggers have previously expressed dismay over the practice of leaving behind dead wood and trees cut when building roads, Rhode says most of them have logged at the base for many years and understand that Ft. Lewis does its forestry to the beat of a different drummer.

Forest Service Study

Ft. Lewis has also been host to a Forest Service research station since 1991. The station is conducting a long-term ecosystem study which focuses on ways to accelerate the creation of old growth conditions, and the spotted owl habitat that comes with it.

Researchers initially plotted out eight 20-acre grids in two separate areas (for a total of 16 grids totaling 320 acres). They then subdivided each grid into 40-meter squares. Plant and wildlife populations were surveyed to provide baseline information before any logging was done, with the intention of looking at the effects of different degrees of thinning over a 20-year period.

Each 40-meter square was then slated for one of three different logging treatments: light-thinning, heavy-thinning, or "open-cut." By doing this, researchers hoped to open up the forest - in much the same way that Rhode's variable density thinning does - and then study the effects on everything from soil composition to flying squirrels. The main difference between the study and what Rhode is doing on the rest of the base is that the study areas will be logged a bit heaver - due to the use of the "open cuts" - in an effort to get the forests out of the stem exclusion stage more quickly.

"We would like to take more trees out in a more patchy fashion than they do to get the understory to come in quicker," says Dr. Andy Carey, who is heading the research.

Carey says that traditional timber management creates a mixture of clear-cuts and stem exclusion phase forests, which can sustain only about 35 percent of the potential biodiversity of a landscape. By limiting clearcuts (or open-cuts), to less than 15 percent of the forest acreage and selectively thinning the rest, says Carey, foresters can virtually eliminate the stem exclusion phase. In additon, he adds, this healthier "working" forest can then harbor about 85 percent of the potential biodiversity of a virgin forest.

As part of the study, researchers have built flying squirrel "nests" by drilling holes into some trees and by mounting boxes on some others. They hope these nests will help to stimulate the natural decay process at the top of some trees, creating cavities that will provide homes for even more squirrels, which are a major source of food for spotted owls.

Carey is also working with private landowners and the state Department of Natural Resources to help them to learn about ways in which they can use this type of forest management to both produce wood products and protect fish and wildlife habitat.

Rare Ecosystems

Because Ft. Lewis sits atop layers of glacial till, the soils are relatively permeable and dry out quicker than soils around much of Puget Sound. These drier soils, combined with an average annual rainfall of about 40 inches - or less than half of what falls in much of the Cascade foothills - have fostered a variety of unique ecosystems at the base. Ft. Lewis is home to the only natural stands of Ponderosa Pine west of the Cascades and contains some of the largest remaining expanses of Puget Sound prairie. The base also harbors extensive oak woodlands, which were never common in Western Washington, but which are now quite scarce.

Ironically, these weather patterns and other soil conditions also make the base a relatively poor area for growing Douglas Fir. The style of forestry practiced at Ft. Lewis could be even more productive when practiced on lands with better soil, according to Curt Soper, the director of agency relations for The Nature Conservancy in Seattle.

"They have a very lucrative forestry program," says Soper. "The fact that they are doing this on soil that isn't that great makes it even more impressive."

The Nature Conservancy has been working with Ft. Lewis for several years in a cooperative effort to help the base identify and manage its rare wildlife habitat. The Army has established five "Research Natural Areas" on the base (unrelated to the Forest Service's research plots), totaling a little under 5,000 acres. These preserves all contain areas of high ecological significance, including the Ponderosa Pine forests, the Puget Sound prairies, the oak woodlands, small pockets of old growth, and some wetlands.

"Ft. Lewis is the site of some of the best, and last, natural remaining habitat in the Puget Sound lowlands," says Gordon Todd, another spokesman for The Nature Conservancy.

The photo above was taken from Rainier Fire Lookout at Ft. Lewis in 1942. The photo below shows the same general area of the army base in 1989.

(photos courtesy of Ft. Lewis)

When large timber companies and the Forest Service drew increasingly vehement criticism during the late '80s and early '90s for the habitat destruction wrought by clear-cuts, they initially tried to dodge the bullet by arguing that large clear-cuts were based on sound forestry and their critics were simply misguided.

As an increasingly incensed public brought political pressure to bear on the timber companies and the Forest Service, the industry gradually began to change its tune. Companies like Plum Creek Timber, once deemed the "Darth Vader" of Northwest timber operators, began to admit that, yes, perhaps they had overdone it "a little" in the past, but things were different now. They vowed that they had changed their ways and asked the public to let bygones be bygones.

At the same time, foresters and wildlife biologists were rapidly rewriting the rules for what was considered appropriate and sustainable forestry. Most notable among them was Dr. Jerry Franklin, a forestry professor at the University of Washington, who has been called the guru of "new forestry."

While the term "new forestry" is now often used quite loosely - so loosely that some say it differs very little from "old" forestry in some of its incarnations - it does have components agreed upon by most foresters. Generally, it is an approach to forestry that looks at logging's effects on an entire ecosystem, and tries to adapt logging techniques so as to minimize the adverse effects on habitat and wildlife, without significantly reducing timber yield. These include, among other things: leaving a buffer zone of standing trees along rivers and streams in order to slow and filter erosion coming off clear-cuts, leaving a certain number of trees per acre - some scattered and some clustered - to provide seed trees and retain some wildlife habitat, and feathering the edges of clear-cuts to follow topographic boundaries rather than straight lines and thereby reduce the visual impact of the logging.

"New forestry is just kind of a prettied-up clear-cut," says Jean Stem, who runs the Forestland Management Committee in Olympia. The committee is involved with efforts to establish guidelines and processes for "certifying" sustainably harvested lumber, just as vegetables can be certified as organically grown (see "Coming Soon to a Store Near You: 'Certified' Wood," page 9).

"Everybody uses the term 'new forestry' differently to try and justify what they're doing," says Ft. Lewis' Rhode. "Someone could say they're 'thinning' and still be removing 90 percent of the trees."

Plum Creek Timber Co., Weyerhaeuser and the Washington Forest Protection Association (the state's major timber industry lobby) regularly run newspaper ads telling readers about their belief in "new forestry" and inviting them to write for informational brochures, or, better yet, arrange to visit some industrial timberland and see for themselves the changed face of the timber industry.

"I would debate what they call forestry," says forestry consultant Keene. "What they call 'new forestry' is the last 40 years of clear-cutting and regeneration harvesting, which is technically DE-forestry. First they deforest, then they replant. It has nothing to do with forestry."

"Let's make sure to compliment them for the first tiny steps away from sheer deforestry," he adds. "Let's make sure to recognize when they start leaving trees and leaving wider buffers - even though it may not by a long shot be perfect - it's still a lot better than what they were doing."

Rhode says Ft. Lewis' forestry program can attribute much of its success to the fact that he and his colleagues have been able to do what they thought was best for the forest, without being subject to the political and economic pressures to cut faced by the Forest Service or timber companies.

"There are different goals. We don't have to generate X number of dollars income from our program here," says Rhode, adding later "Let's face it, Weyerhaeuser has to pay stockholders."

One can try to loosely estimate the economics of selective logging with "new forestry" clear-cutting by comparing the yield of a stand over a long period of time using the two methods. For example, first calcuate how much a forest owner would make by cutting an entire stand at once and simply putting the money earned in a savings account for 30 years. Then compare that to how much a forest owner would accumulate - including interest - by selectively logging the land each year over the same period.

More likely than not, the clear-cutter will have a little more money in the bank at the end of 30 years. However, when you calculate the value of the standing timber at the end of that time, the selective logger will have an abundance of mature trees, whereas the clear-cutter will have only a stand of skinny 30-year-old trees - and therefore have less "equity" in the forest.

More importantly, as Keene points out, when people start to talk simply in economic terms, they are leaving out the value of all the other benefits a healthy forest provides: fish, wildlife, improved water quality, and human enjoyment, to name a few. If these were all given a monetary value and added to the balance sheet, the selective logger would come out far, far ahead.

"Money does not provide the amenities that a forest provides," Keene adds. "The problem is the only amenity we value is the value of the timber."

Forestry professor Franklin cautions that comparing Ft. Lewis' methods or production levels with other timberland is not valid for a number of reasons, among them soil conditions and the Army's training needs. While he thinks that the base's foresters have created an important model of how partial cutting can be used in Douglas Fir forests, he says that Ft. Lewis-style forestry is simply not well-suited to large industrial landowners. However, he does believe that small private timberland owners and the Forest Service can learn a lot from the Army.

Keene agrees, saying that the whole idea of annual Forest Service cut levels being dictated by Congress is a "bastardization of earlier directives." He says the wording of the original legislation establishing the national forest system stressed maintaining the forests as reserves, to be used by generation after generation. "I would argue that where private lands may be held for quarterly profits, public lands are held for long-term inheritance and they're to be maintained in a perpetual state of productivity and diversity."

If Ft. Lewis is to serve as a model for doing just that, Keene concludes, then forest managers must escape from a mindset that only focuses on the immediate economic value of a forest. "If you're going to practice ecosystem management, you're going to have to get rid of the forest economist. Boom, they're out of here. We don't need beancounters. We need caretakers. We need stewards. That's the only way you can manage a forest."

|

|

|

|

|