by Brian King and Mark Gardner

A fun transit story goes like this; the year is 1850 and a group of traffic engineers are seated around a conference table in a government building located in downtown London, England. The men around the table have been working hard all day trying to create a long range plan to meet the growing transportation needs of the city. Finally, the fellow at the head of the table clears his throat and the others fall silent, waiting to hear what this man, apparently the most senior and respected of the group, has to say. "I say, gentlemen," he begins, "if the trends outlined today at this meeting continue for, say, the next 50 years or so, our grandchildren will enter the new century unable to move about at all in London, and they will be up to their ear lobes in horseshit besides." This spring, on March 14, the voters of King, Pierce and Snohomish counties will have the opportunity to vote on a rail transit proposal from the Central Puget Sound Regional Transit Authority (RTA). While we can't analyze the entire plan here, it is worthwhile to examine some of the fundamental questions it poses before the debate really heats up, and we're all knee-deep in it. Even while the discussion turns toward cost estimates, engineering specifications, ridership projections and other technical issues, a little common sense can still take us a long way in guiding our upcoming choice. Is the current plan a good deal for the average working person? Will it solve, or at least contribute toward a solution to our growing problems in getting from one place to another? Is it environmentally sound?

If it passes at the polls, we will have agreed to an increase of .4% in the local sales tax and .3% in the local vehicle licensing tax, in exchange for a light rail system for the Puget Sound Region. This will be the seed money for a $6.7 billion project that will take 16 years to complete.

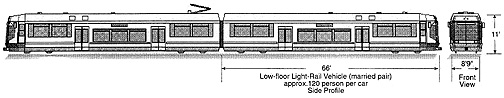

The heart of the RTA proposal is a plan to build a $4 billion light rail train system. Light rail means that the trains will, to some extent, operate on existing city streets. This differs from heavy rail systems, like BART in the San Francisco Bay Area, which are too heavy to operate on streets, requiring their own supporting bed. The line would run from Downtown Tacoma in the south to Lynnwood in the north. It would also follow I-90 across the lake, through Bellevue to Redmond.

Along with the light rail system, the RTA has included $574 million in its proposal for upgrading existing tracks (where freight and Amtrak now operate) and operating a commuter train between Lakewood - south of Tacoma - to Everett. Bus service would be improved, lines would be added and extended. Some money has been set aside to make use of public transit in the three county area easier by making it possible to transfer within the system using the same ticket you purchased at the beginning of your trip.

Will this new system end the frustration of that endless morning trip across the lake or the agonizing slowdowns on I-5? Not unless you are able to leave your car at home, which is what it is hoped the new system will enable you to do. For the unlucky commuters still in their cars, the best to hope for is that things will not worsen much over the next 15 years if the new system is built. These were some of the consensus views expressed at a meeting held in Vancouver, BC last October 22 & 23 attended by some 200 government and business leaders from the area covered by the RTA.

Since even supporters agree that this system won't actually eliminate congestion, critics are assailing it as an expensive boondoggle. But the appropriate question is: expensive compared to what? Critics ought to be held accountable for explaining how an expansion of the automobile and bus status quo will do a better job of getting us around. Consider the difficulties in expanding the current system. What communities will accept the new highways and bridges necessary to handle increased demand? How can the expansion of a bus-only system be accomplished without hopelessly fouling existing traffic corridors, thus slowing them down further? And, will the immediate expenses be any less than that of a rail system?

The light rail proposal is expensive, but these costs need to be put in perspective. Consider first the personal costs of auto travel. Most people are so used to shelling out enormous amounts of cash in steady increments to sustain their automobiles that they rarely pause to consider the total yearly out-of-pocket costs. The AAA has estimated the average costs per mile of car payments, insurance, gas, and registration for a relatively new, moderately priced car at about 39 cents a mile for 1993. If a person drives 5000 miles per year, this equals $1,950. Now multiply this by two for a two car family. This total of almost $4000 makes the $100 cost per household per year for light rail pale to insignificance.

Now consider the tax subsidies going to auto travel. The World Resources Institute estimates that direct fees such as the gas tax and tolls pay only 60% of the true costs of driving. The remaining 40% comes out of general revenues, 90% of which comes from local taxes. The Institute for Transportation and the Environment estimates that the city of Seattle alone spends about $13 million a year for construction and maintenance of roads over what is generated by auto fees.

Then there is the environmental cost of autos. According to People for Puget Sound, run-off of various petroleum products associated with cars pollutes our waters to the point where autos can be said to be contributing significantly to the decline of Salmon runs. Everybody is aware of the extent to which car use pollutes the air while also undermining our local quality of life in numerous ways such as noise, congestion and actual physical danger.

Even those who are too individualistic to ride public transit ought to consider another point which almost never gets raised in the debate: failure to provide those who would ride transit with that option forces virtually everybody to own a car and crowd onto the highways. With a good transit system, many households may forego a second car, or drive the ones they do have significantly less. Presently, we're at the point where bus travel just doesn't cut it on many corridors, which is forcing more and more people to rely on cars. It's a vicious circle, and a good reason for even the most die-hard auto lovers to vote for the system.

Pierce County Executive Doug Southerland pretty well summed things up at the Vancouver meeting saying, "If it can't be done now, it's going to be 20-25 years before the traffic crisis is of such a nature that there's nothing left to do but do it."

Will residents of Puget Sound actually get out of their cars and support the new system? According to a recent poll by the RTA, 79% of the people said they would use the new system. Evidence in other cities shows that once such systems are built, support for rail tends to expand. Communities usually experience considerable difficulty in getting local voters to approve the first step, to lay track and run the first trains. Once a system is up and running, , it becomes much easier to go back to these same voters and gain approval for expansion of already existing systems.

Over and over, up and down the West Coast the pattern is repeated. Voters in San Diego, Los Angeles, Sacramento, Portland-Vancouver, WA and Vancouver, BC have all passed ballot measures to raise taxes to fund extensions to existing rail systems. According to Puget Sound RTA spokesperson Denny Fleenor, controversy in the Portland-Vancouver, WA area centers around where the new transit extensions will be placed, not whether or not to build them. Most folks want the trains to be close to where they live so they can use them more. [Fleenor also notes that we stand to lose $300 million in Federal funding that probably won't be available again for the foreseeable future, should the measure fail in March.]

Perhaps as important as any efficiency gains is one intangible result of a great transportation network: the potential of transit to help build community. Most people in around Puget Sound use their cars for much, if not all, of the travel they do for work, visiting family or friends, etc. Many people have never experienced the pleasure of making their way to work every day with a group of people who ride the same bus or train. Driving alone in a car contributes to the all too prevalent feeling these days that it's "every person for themselves." Having a large percentage of our population using public transit would help us knit our social fabric back together, and help us remember that we're in this life together.

But ultimately, the light rail system should be looked upon as only the beginning of a solution to our current transportation mess. For now, citizens need to question the tendency of some in local government and the RTA to create an extensive rather than an intensive transit system. That is, they wish to link together disparate population centers and reduce peak congestion through central corridors primarily as an economic development tool, not as a means of getting a large proportion of the population out of their cars. But from an environmental and land use perspective, it is better that we create more extensive links between existing high density areas, and to encourage more density in those areas, rather than to create more north-south links for a giant Tacoma-Seattle-Everett megalopolis. From this perspective it is good that Everett has for the time being been left bereft of a light rail station, temporarily preventing it from becoming a bedroom community for Seattle.

We also need to create policies which will put non-auto forms of transportation on equal footing. How about a policy that calls for safe bicycle commuting corridors for every area of the region? What about creating more pedestrian-only zones served by transit throughout the city? What about aggressive transit pass and ride-sharing programs being adopted for all businesses in the region, such as has already occurred successfully at the UW? Future issues of the Free Press will explore these and other ideas for a more balanced and environmentally-sound transportation system.

WAfreepress@gmail.com

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the February/March, 1995 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1995 WFP Collective, Inc.