by Eric Nelson

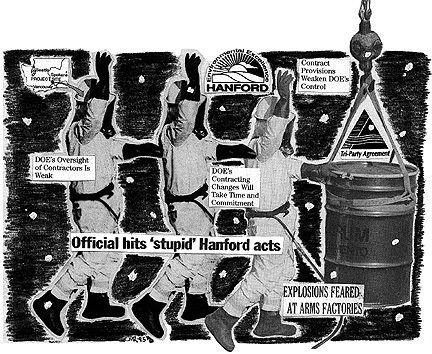

illustration by Matt Robesch

The Free Press

Two years ago Bill Clinton and his frontman Al Gore promised us a new era of environmental awareness and restoration. The ensuing Clintonian compromises resulted in backpedaling on pesticides, pollution, and little cleanup of toxic waste. Today, the Department of Energy's nuclear weapons sites, among the most toxic and dangerous in the world, are in jeopardy of losing their cleanup funding when they pose a greater risk than ever.Activists who follow Hanford have long worried that one day Congress would lose patience with DOE's ineptitude, put a fence around the place, and walk away. That fear is close to reality with a good chunk of Bill Clinton's proposed "middle class tax cut" coming out of DOE's cleanup budget. The new Republican Congress didn't even have to ask for the cuts. Clinton offered them up on silver platter.

Of course, Clinton's tax cut, to be funded with budget reductions, is just a proposal. However, a report by Mark Crawford of the trade journal Energy Daily suggests that DOE's budget is all but "locked up" for the next five years. The numbers look like a return to an austere Cold War: $10.6 billion dollars in cuts to DOE's budget, but a $2 billion increase in DOE defense spending. Where do the cuts come from? The biggest is a $4.4 billion whack out of DOE's $6 billion environmental budget.

The implications for sites like Hanford are profound. Right now, Hanford is a disaster waiting to happen.

Site of the world's first production reactor which produced plutonium for the Manhattan Project, Hanford encompasses a 560-square mile area strewn with nine decommissioned weapons reactors, trenches filled with radioactive materials, a radioactive water table that threatens to seep into the Columbia River, and 177 leaky underground waste tanks filled with mysterious "witches' brews" of plutonium and mixed organic solutions. Those tanks' contents are poorly understood and highly unstable. With a half-century legacy of accidents and environmental irresponsibility, Hanford is regarded as the most toxic site in the Western hemisphere.

Of course, bemoaning Hanford's budget woes is politically difficult when taxpayers have poured $7.5 billion into Hanford since 1989 with few results, other than the enrichment of bloated contractors who bill taxpayers for chauffeur services and $300 dollar-an-hour legal services to defend against whistle blowers. Estimates by Hanford watchdog groups and the General Accounting Office suggest that as much as 67 cents out of every dollar spent at Hanford is wasted.

Cutting the environmental budget for the nation's nuclear complex may trim some pork. But such cuts do little to answer how Hanford and its sister sites can ever be cleaned up, or at minimum be maintained safely. Clinton's proposal appears to be a full-blown retreat from the most ambitious, but necessary, environmental project in history.

Hanford watchdog groups say Clinton's budget proposal is a dangerous omen for safety and the environment. Earnest efforts to reform the complex's priorities and the way it is managed ran into a fiscal "train wreck," said Bill Mitchell, former director of the Nuclear Safety Campaign, a Seattle policy group.

Mitchell notes that Washington state has been left with an impotent congressional delegation incapable of fighting for funding when it seems that the complex is moving back to a budget system where each site fights for its own money. Given the power of South Carolina's delegation, Savannah River is a sure bet for more cleanup dollars.

"We're saying 'If you are going to cut the budget, don't do blanket cuts, target them (to eliminate inefficiencies),' " said Cynthia Sarthou, counsel for Heart of America, a Seattle Hanford watchdog group.

As Clinton attempted to stave off criticism from the Republicans who swept Congress in November, DOE's environmental restoration and waste management budget represented a tempting target. According to reports, presidential advisor George Stephanoupoulos wanted to eliminate DOE entirely, turning over control of nuclear weapons maintenance and dismantlement to the Department of Defense. In an effort to save her department from the ax altogether, say observers of the nuclear complex, Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary was given little choice but to surrender her agency's environmental budget.

Two years ago, Clinton got off to a good start with the appointment of O'Leary and backed her up with good people. Ambitious plans were drafted by her advisors from the Natural Resources Defense Council who had studied nuclear waste issues, and at times sued, DOE under previous administrations. Secretary O'Leary has spent the last two years implementing an "open door" outreach policy with concerned citizens, and declassifying secret documents about DOE operations, including illegal medical experiments involving radiation exposure.

But O'Leary has also spent two years engaged in running battles with the entrenched bureaucrats who, along with a cabal of bloated contractors like GE, Westinghouse and Battelle, run the DOE sites and would rather go back to the days of making bombs and making waste. A 1992 report of the federal General Accounting Office summed up O'Leary's dilemma:

"DOE's efforts to clean up the legacy of weapons production have been hampered by technological, compliance, and management problems that have led, in turn, to missed milestones and escalating budgets. In the quest for weapons supremacy, DOE and its contractors placed an overriding emphasis on weapons production and relegated environmental, safety, and health issues to a minor role."

It's a hell of a job to turn around the legacy of 50 years of bomb-making and O'Leary has said repeatedly she would only stay on for one term. Now, after two years, O'Leary's boss has pulled the rug out from under her and the various stakeholder groups that pushed for cleanup at sites like Hanford.

Few of the Hanford projects described in the Tri-Party Agreement, the compact between DOE, the Environmental Protection Agency and the state Department of Ecology have begun. Among DOE's various obligations under the agreement is a pledge to maintain necessary funding for cleanup. Paragraph 138 of the Tri-Party Agreement states: "DOE shall take all necessary steps to obtain timely funding in order to fully meet its obligations under this Agreement." Now states with polluted DOE sites are bracing for protracted legal wrangling to hold the federal government to its word.

Jerry Gilliland, a spokesman for the Department of Ecology in Olympia, said there has been no official request yet by the energy department to rework the Tri-Party Agreement. "We don't know what the budget cuts mean, and it's OK if they make deep cuts through efficiencies. But we don't want to re-do the milestones," said Gilliland.

The milestones set timetables for completion of huge projects at Hanford by 2018. These include construction of a low level radioactive waste treatment plant, research on the 177 unstable and leaky liquid waste tanks, glass vitrification of waste, and protection of the Columbia River (slated to receive 10 percent of Hanford's cleanup budget.) Plans for the Columbia restoration project are supposed to be produced within the next 18 months. "We hope to see a lot of cleanup there," said Gilliland.

However, Cynthia Sarthou of Heart of America believes the state will have a hard time holding the federal government to its promises. "Department of Ecology's position is that (the Tri-Party Agreement) is enforceable, but is it?" she asked. The legal certainty of the Tri-Party Agreement has yet to be tested in court. Already, the National Associations of (state) Attorneys General, representing states with polluted DOE sites and cleanup agreements similar to the Tri-Party Agreement, has fired off a letter to the federal government demanding that it stick to its commitments.

So far, DOE's rhetoric under the Tri-Party Agreement has not been matched by its actions. According to budget analysis by Heart of America, DOE has promised speedy cleanup of the Columbia, but has budgeted only 13 percent of 1995 cleanup funds on actual environmental restoration. DOE spends much of the money producing studies and last year spent more money on Westinghouse's "overhead" than actual environmental restoration. (A report produced last year for DOE noted that cost over-runs on DOE contracts average 48 percent by the time the work is completed.)

Meanwhile, mysterious budget items continue to appear. Rumors are circulating among Hanford activists that DOE is planning an environmentally dangerous mixed waste incinerator for the site. A reference to it appeared in another site's budget, although Hanford officials deny any incinerator is in the works for their site.

Given this track record, it's easy to conclude that DOE is hopelessly adrift in a culture of secrecy and inefficiency. Among the most vexing issues that must be resolved is the disposition of 26 metric tons of plutonium at 35 sites which could "potentially threaten the public and the surrounding environment," according to a DOE report released last year. Hanford has 4.4. metric tons. Rocky Flats, not far from Denver, has even more.

How to classify the plutonium and where to store it has been a matter of intense debate as it is recovered from various facilities and removed from nuclear warheads. Defense-minded DOE officials and the Pentagon consider it an "asset." DOE's high-level environmental administrators consider it "waste." In 1992, a bureaucratic battle developed over the dangerously unstable plutonium scrap left in Hanford's decommissioned Plutonium Finishing Plant. Westinghouse officials proposed restarting the dangerous plant in violation of federal environmental laws to further refine the scrap into usable plutonium, but that plan appears to be forestalled for the moment.

One high-level DOE official, in charge of planning cleanup projects from DOE headquarters in Washington D.C., told the Free Press at the time, "We've got a serious problem with the defense mentality out there."

On the defense side of Clinton's proposed DOE budget is $1 billion for the National Ignition Facility (NIF), a replacement for older lasers at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratories. The NIF, to begin construction in 1997 and be completed by 2002, will serve weapons physicists and fusion energy research. Its operating costs will be $60 million a year.

Other defense items in the budget include funding to produce tritium - a necessary ingredient for nuclear warheads - which DOE has been lacking due to reactor problems at its Savannah River site. According to a report in Energy Daily, DOE will explore a new method of producing tritium with particle accelerators, which bombard targets with protons.

With less spending on environmental cleanup and more on defense, the old guard has accomplished a fait accompli. Observers believe the administration's early attempts at reform resulted in a backlash among entrenched powers within industry, the DOE and Department of Defense.

"Fundamentally, the insiders are outmaneuvering the newcomers," said Saul Bloom, director of the Arms Research Center, a San Francisco group focusing on the cleanup and conversion of military bases. The process took shape in 1993 when the EPA's Office of Federal Facility Enforcement was eliminated. "What's going on now is that the bureaucracies are consolidating within the agencies themselves."

-Eric Smith, a Seattle writer who follows Hanford issues, contributed to this report.

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the February/March, 1995 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1995 WFP Collective, Inc.