by Brian King

We seem to be on quite an anti-crime binge these days. The United States has become the #1 per capita jailer of all the countries in the world and Attorney General Reno is promising to speed up prison construction to accommodate the additional Federal prisoners that are expected to land in the nation's jails as a result of Bill Clinton's recently passed crime bill.

We seem to be on quite an anti-crime binge these days. The United States has become the #1 per capita jailer of all the countries in the world and Attorney General Reno is promising to speed up prison construction to accommodate the additional Federal prisoners that are expected to land in the nation's jails as a result of Bill Clinton's recently passed crime bill.

Here in Seattle, anti-crime programs have been received by the public with a little less enthusiasm. People in the Northwest, especially African-Americans, don't seem to be quite as anxious to jump on the "lock em' up" bandwagon as some in other parts of the country. The federal Weed and Seed program, operating in Seattle for the last couple of years, offers some interesting history.

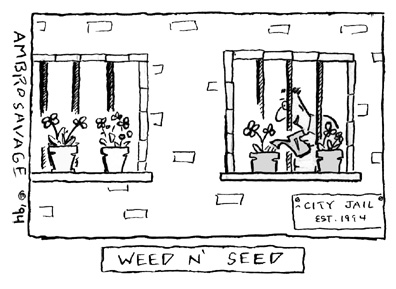

3 years ago, in the wake of the Los Angeles riots, Weed and Seed originated as one of the Republicans' principal domestic programs designed to address what they saw as the social and economic deterioration of America's inner cities. In March 1992, Seattle City Council member Margaret Pageler said, while commenting on growing opposition to Weed and Seed, "the name of the program is enough to raise anybody's hackles", and many Seattleites agreed. Looked at closely, however, the name sums up fairly well the intent of the program. Weed out, through arrest and stiff federal sentences, the bad guys in high crime areas. Then plant social program seeds to involve all the innocent folks in wholesome activities designed to prevent them from deciding on lives of crime and thus becoming new bad guys.

Many in Seattle's African-American community didn't see it as all that simple when the federal proposal documents for Seattle's Weed and Seed program were leaked in January 1992. Street sweeps, where everybody on public streets in an area designated as "high crime" would be taken into custody and forced to prove their innocence, frightened many Black community leaders.

Arresting everybody on a public street just because they happened to be out at the time of the sweep would completely ignore the long established tradition in our country of due process before the law. Who could say that many innocent young folks wouldn't be caught up in these sweeps, possibly having their lives damaged by being marked as having been in jail?

Other causes for concern were the stiff sentences that first time offenders would be receiving as a result of arresting people on federal charges, and the overall federal control of the program in the city to be exercised by then US. Attorney Mike McKay. To many, this program appeared to be a long step on the road toward loss of civil liberties and toward federal control of police activities in Seattle, hardly an inviting prospect.

The "Seed" portion of the program wasn't very appealing either. Many of the proposed social programs in the leaked document appeared to be planned as police department programs that could easily be seen as being a source of information gathering, and recruiting informers in the targeted communities.

Weed and Seed programs were offered by the federal government to 16 cities, including Seattle, in early 1992. Many of these cities, like Trenton, New Jersey, quietly went along with the wishes of the Feds and instituted programs with much of the increased police activity intact, including the constitutionally questionable street sweeps. Not so Seattle.

When word of the proposal for Seattle reached Community leaders like Arnette Holloway, president of the Central Area Neighborhood District Council, and Harriet Walden of Mothers Against Police Harassment, a determined effort was set in motion to derail the federal initiative. Press conferences were held, lively public demonstrations took place, and the Seattle Coalition Against Weed and Seed was organized, which met weekly and had an active membership of approximately 100 people. The Puget Sound Coalition for Police Accountability held a news conference where a list of 55 community groups opposed to Weed and Seed was distributed.

The public opposition to Weed and Seed had a dampening effect on the support the proposal had initially received from members of the Seattle City Council. Council member Pageler announced in September of 1992 that Weed and Seed was "dead for this year." It appeared that grass roots opposition to this plan for increased police activities in our city had caused it to be dropped from the local agenda.

But Weed and Seed was adopted in Seattle at a meeting of the city council in December, 1992. What had changed? Just a presidential election where the heartless Republican, George Bush, was replaced by a Democrat, Bill Clinton. It seemed that Clinton's election had made it possible for council members to vote for increased police activity, since there wouldn't be a Republican president in charge of things after January.

The effect of the grass roots opposition does, however, appear to have been lasting. Dan Fleissner, manager of planning and finance for Weed and Seed in the Seattle police department says, "There haven't been any street sweeps in Seattle, or federal arrests, resulting from this program." Martin Mungia, of the American Civil Liberties Union agrees. "Public opposition to Weed and Seed caused the city council to insert provisions in the Seattle program prohibiting the constitutionally questionable parts of the federal plan from being implemented here. The sweeps were canceled in this city." This stands in contrast to other Weed and Seed cities, such as Chicago, where street sweeps have been used, according to Fleissner.

Harriet Walden warns, however, that some aspects of the Weed and Seed program, like the organizing of neighborhoods by the police and appointing block captains, amount to "nothing but a police spy program." She strongly feels that community organization should be led by the "grass roots, not the police."

According to City of Seattle budget documents, the first year of Weed and Seed, now completed, was a 1.1 million dollar program overseen by the Seattle Police. The weed, or law enforcement, portion of the program accounted for $530,000, with the seed portion receiving the remaining 570,000. Mungia says that "it appears that most of the weed funds have been folded into already existing police activities, making it hard to determine the actual effect of the program here in Seattle on such things as numbers of arrests."

In the seed, or social, portion of the program is a $200,000 allocation-almost half of the total- to Seattle Team for Youth, which is an existing city program that brings young people considered "at risk" together with police officers who act as case managers for the young people. The officer-counselors help their clients look for work, secure drug counseling or other services needed by the at risk youth.

Seattle Team for Youth Activities involving more than a hundred Seattle kids, such as helping youngsters gain entry level job experience, basic job skill training and hiring ex-gang members to help others leave the gangs, can hardly be faulted. One does wonder at the advisability of involving police in this process, with their penchant for keeping records and passing along information.

Often times, during the discussion of public safety issues these days, one is left with the feeling that most government officials only want to deal superficially with crime. "Let's just lock em' up and throw away the key" they often seem to say. Maybe a more thoughtful approach would include the question of hope in people's lives. Give a person a decent chance at landing a secure, skilled job and he/she would probably try pretty hard to avoid drugs and gangs. If private business is not able to provide people with valuable work and economic opportunities, perhaps the government should. Coupling needed social programs to an increase in police activities sends the wrong message. If the social programs work, and everybody has a decent job, it's hard to imagine there would still be much of an argument for more cops.

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the October/November, 1994 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1994 WFP Collective, Inc.