by Andrea Helm

The Free Press

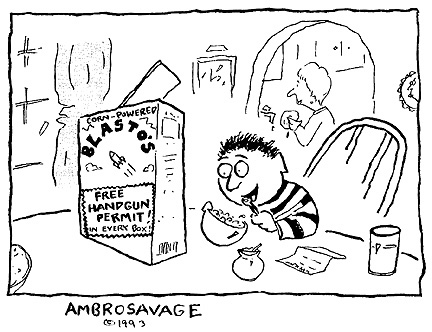

illustration by John Ambrosavage

Life in rural Mississippi, where I'm from, meant guns: hunting rifles, shotguns, pistols, BB guns. Boys carried cap guns or pellet rifles. My dad taught his three daughters to shoot, as well as to aim a compound bow and arrow.

Elmer Fudd chased Bugs Bunny with a shotgun on Saturday mornings. On Sunday-afternoon spaghetti westerns (after church where we'd just been told to love thy neighbor as thyself and thou shalt not kill), someone always got shot, but no guts ever oozed onto the floor.

Guns were just a way of life deep in the heart-a Dixie; albeit, they were taken for granted in a different way than they are today. Shooting one of my family members was never an option, although my alcoholic, wife-beating father offered enough motive and opportunity. Happens all the time now.

What's changed so drastically in the past 15 years? Plenty, according to "The Face of Violence: Washington's Youth in Peril," a May 1993 report by the Washington state Department of Community Development. First and foremost is our increasing appetite for and tolerance of violence.

Consider some statistics: in Washington state, nearly half of all murders, rapes, robberies and assaults are committed by people aged 10 to 17. Almost 3,000 youths were arrested in 1991 for violent offenses. This figure has doubled in the last 10 years.

In 1992, 54 of the state's 260 homicide victims were aged 15-24, giving that age bracket a homicide rate more than double that of the general population. Many homicide victims were younger still - 23 were under 14, and 15 of those were under 5.

"Kids these days grow up in war zones," says the Community Development department's Liz Mendizobal. "They grow up in domestic violence situations; they see violence on TV, watch Rambo movies and hear violent talk from their peers."

Our society spends hundreds of millions of dollars treating the end result of a lifetime of negative influences, yet skimp on life skills early on. "You can't rehabilitate someone who has never been habilitated," Mendizobal said. "We have to set a new example of behavior they have never seen before."

These "habilitation" programs being tested in pilot schools and communities include after-school activities to combat boredom, along with counseling. The focus, she said, is on developing stable, working relationships with good role models - a "slow integration into help."

More than 4,000 Washington state school children are getting health, nutrition, job training, parenting, anger management and conflict resolution skills through this innovative, grassroots program funded with $378,000 from the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance.

"Most people, especially kids, have never been taught that it's OK to walk away from a fight," she said. "We're teaching decision-making skills. We're developing trust. We're building a sense of grounding, a sense of future, of hope and a way to break the cycle of violence ... not just for 'at risk' kids but for society as a whole."

Anger management and other programs already are part of the curricula in some Seattle schools, and more may be on the way if Gov. Mike Lowry's "Youth Agenda" proposals succeed in the Legislature this winter (see main story.)

This kind of forward thinking also is going on in places like North Carolina, where the privately funded North Carolina Education and Law Project has come up with a 13-point plan to "stem the tide of violence in our schools and move on with the task of better educating all of our children." Released last March, the Project's "Time for Action" report calls for a wide range of progressive reforms, including peer mediation programs in schools, multicultural education, stronger gun control, behavior improvement programs and enhanced dropout-prevention measures.

And in Oceanside, Calif., students at Roosevelt Middle School - acting as mediators - are helping each other settle feuds that in the past have been resolved with fists or weapons. Other school-based programs like this no doubt will crop up if funding measures pending in Congress survive. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the midst of trying to show quantitatively what so many people have seen first hand - that the programs are working.

Here in Western Washington, an organization that's probably best known for its opposition to nuclear weapons is broadening its mission in hopes of reducing the amount of violence that occurs in our own communities. SANE/Freeze, which has 17,000 members statewide, has just launched its "Peace in the Streets" campaign to convince policy makers - and the rest of us - that the time has come to end the wars being fought within our own borders.

"There was a tremendous neglect of social concerns during the 12 years of Reagan/Bush," said SANE/Freeze's Lance Scott of Seattle. "Communities were not supported. And the violence industry was. So it's no big surprise that we're finding more violence in our communities."

Scott said that fellow progressives are not only battling the government to shift its priorities and spend more money on social programs, but they're also butting up against their ideological opposites.

"If we leave it up to the law-and-order types to solve our problems, we'll be on a path to martial law," he said. "People are scared, and there are a lot of people who would be willing to give up their rights to allow for police-state sort of solutions."

Like the DCD's Mendizobal - and the governor, for that matter - Scott is pushing for anger management and non-violent conflict resolution programs to become more pervasive in schools. The way he sees it, such a strategy is critical to changing the consciousness of today's youth.

"We have a history of using violence as a first resort instead of a last resort - whether it's in a foreign country or in the neighborhood," Scott said. "If young people see the government choosing violence, what sort of example does that set?"

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the December/Jan, 1994 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1993 WFP Collective, Inc.