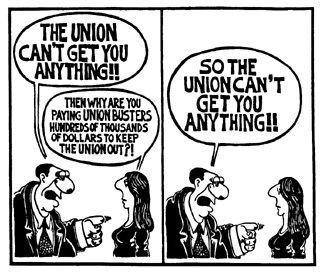

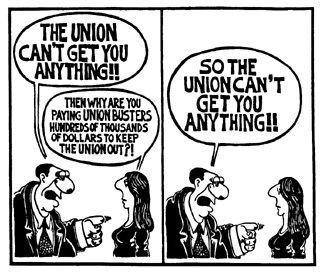

How management battled the union effort and successfully undermined its support is a case study in union busting. While this push for union representation failed, it is a prime example of how the economy of the '90s may be planting the seeds for a resurgence of organized labor.

Nouveau Blue Collar

Most Daniel Smith employees are in their 20s or early 30s. In the warehouse, where about half of them work, many workers are artists in their spare time and most of them have a college degree. Starting pay for warehouse workers is $6 an hour, with more experienced workers making up to $9 an hour. ILWU, Local 9 representative Tony Hutter said that Daniel Smith employees had the lowest average wages of any warehouse workers the union had encountered in Seattle.

While not quite starving artists, many of the workers say they live paycheck to paycheck. If you are paying off any student loans, $6 an hour might by be enough to just scrape by on. These warehouse workers are representative of a growing sector of the American work force: college-educated young people who work full time but can barely pay the bills. Mix over-educated, underpaid workers with capricious and unresponsive management and you have fertile territory for union organizing.

Many employers have responded to the recent recession by hiring a succession of temps, thereby avoiding the need to give any of them raises. In addition, many full-time jobs with medical benefits have been transformed into multiple part-time jobs without any benefits. Daniel Smith is no exception.

Jenny Schmid was hired at Daniel Smith in December of 1992 as a call-board person, meaning she would work a flexible part-time position. When she was hired she was told she would receive part-time benefits, including paid time-off and some medical benefits.

After a couple of months on the job, she asked about the benefits and was told that she would receive them after she'd worked 500 hours. Once she had worked 500 hours she asked where her benefits were and why she wasn't getting paid time off. Personnel gave her the runaround, said Schmid, and could not decide whether she would get part-time benefits at all. After the company found out that employees had signed union cards, all of the call board employees began receiving benefits.

"They're just really cheap," Schmid said. "They've been hiring more and more temps. They wanted to give this call board position even less benefits than a part-time person, even though I was working 30-plus hours a week, and working a flexible schedule which is harder to do."

Soon after Schmid was hired, the company instituted a wage freeze. Then managers cut workers' break time from 15 minutes to 10 minutes, with no explanation, and told workers in the warehouse that they could no longer play music because they were "abusing" the privilege.

"There's no point in cutting a 15 minute break to 10 minutes," Schmid said. "They wanted to save money. They just multiplied five minutes times 90 employees or whatever and came up with some profitable total. Then the next day they brought in cake for everyone because we'd earned a million dollars for the company that month."

While they may have been able to have their cake and eat it too, they had five minutes less in which to do it. (The company has since restored 15 minutes breaks and allows music in the warehouse).

Various Daniel Smith employees criticized the company's lack of a grievance procedure. Other allegations against the company included unjust firings, refusal to pay some overtime and one situation in which a woman who had worked for the company for several years trained all the new male employees in her department and within a couple of months they were making more per hour than she was.

When contacted at home, Daniel Smith's president and CEO Bill Crumbaker refused to discuss the company or the union vote. "I just don't have any comment to make at this time." Employee services director Greg Martel did not return phone calls.

Who Ya Gonna Call? Union Busters!!

The beginning of the Daniel Smith employee handbook has a full page describing the company's "union-free work environment." Before it discusses scheduling or overtime or leaves of absence it addresses why the company does not need a union: "When it comes to problem solving, no one knows better than you and your fellow workers at all levels. Problems should be discussed with people inside Daniel Smith who can get them resolved."

Of course, disgruntled employees contend, that's exactly the problem solving approach that has left them banging their heads against the brick wall of management.

In April, Schmid and several other employees decided that the only way to get management to respond was to try to unionize. Two days after their first meeting with the union, the company found out and held a meeting that all employees were required to attend. This was the beginning of their rhetorical assault upon the union.

Soon after, employees were being paid to sit in meetings with Susan Ogden, a "management consultant" from Mercer Island, who had them take personality tests and explain why they were not happy with the company. Employees were encouraged that someone was finally listening to their complaints. "She seemed very sympathetic," Schmid said, "but we knew it was a lost cause the day we saw her get into the CEO's gold Lexus and play with the controls."

Ogden did not return phone calls from The Free Press.

Apparently Ogden did not pan out, because then the company brought in the big gun. Bill Armstrong had a proven union-smashing record, having worked on the decertification of the Nordstrom's union. He was flown up from California to tell employees why joining a union was the last thing they wanted to do.

F rom April until the union vote, Daniel Smith employees sat in more than 20 hours of meetings with the two union busters. The company handed out "fact sheets" on the ILWU, raising every possible argument against unionization, urging employees to vote against "this union thing" and telling them to "see your supervisor if you have any further question. VOTE NO!!"

Most of the employees had never had any contact with a union before. Few of them even knew someone who was in a union. The seeds of doubt that the company was sowing easily took root among workers who only had vague ideas about unions based upon knowledge of the Teamsters and its mafia connections or anecdotes about abuses of union dues. Nonetheless, the union busters' hard sell almost backfired. Armstrong walked out of one his last meetings in disgust, as employees became openly antagonistic and unresponsive to his tactics. "I've never met such a snake," Schmid said.

"I thought (Armstrong) was a jerk," said catalog sales representative Roxy Darice, "but so was the union rep. It was all shuffle your feet and blow smoke." Although she voted against the union, she said she changed her mind several times prior to the vote and the consultants almost had the opposite effect of getting her to vote for the union.

While the overall vote was 52-18 against the union, the election was divided into two units by the company - retail/phone sales in Seattle and the warehouse in Tukwilla. Each unit could have approved the union separately. The union was routed in the retail store 37 to 4, but the warehouse voted 15 to 14. The union needed 50 percent of those who voted, plus one, for certification.

The Company's Trump Card

At the beginning of the effort to unionize, the company's rarely seen owner, Daniel Smith himself, wrote a letter from his ranch in Eastern Washington explaining that he was not going to involve himself in the dispute. In the week before the vote, he obviously realized the extent of the problems at his company and he made a personal appearance.

"The union buster told him he had better get his ass in here," said Bob Jordan, a frame cutter in the warehouse. "(Daniel Smith) came riding in on his white horse and schmoozed and people ate it up."

While every employee contacted for this story (including one manager who preferred to remain anonymous) felt Smith's appearance was part of a last-minute strategy to defeat the union, few of them doubted his sincerity when he promised that changes were going to be made. Some were more cynical about what those vague promises of change would translate into when addressing employee grievances.

"People believe Daniel Smith," said Jeff Ebel, a warehouse employee. "He's an artist himself, a no-nonsense cowboy-boots-and-jeans kind of guy. He doesn't put himself on a pedestal and says he was kept in the dark by the CEO."

But Ebel argues that the changes that Smith is promising will be limited to revamping the catalog, lowering some prices and improving customer service. Ebel feels that as long as the CEO and certain managers remain, nothing will change. "We've been manipulated so many times," he said. "It's still a bunch of bullshit, they're not going to change anything. Daniel Smith could care less about the way employees are being treated. He's losing customers. He's worried about his name."

After the election, Schmid said that she would give her two weeks notice. "I see no future here, especially for me," she said. She attributed the union's loss largely to employees' fears of confrontation and change. She said that prior to the union organizing effort employees complained incessantly about the company and management, but when it came time to put their money where their mouth was they took the easy route out - not changing anything.

"At least we got management to face up to the fact that they made a lot of mistakes, she concluded. "At least we fought."

This story was updated in the Sept 1993 Issue of WFP

Please see "Union-Busting Boss Loses His Perks"

[Home]

[This Issue's Directory]

[WFP Index]

[WFP Back Issues]

[E-Mail WFP]

Contents on this page were published in the September , 1993 edition of the Washington Free

Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1993 WFP Collective, Inc.