"Geographic Fragmentation" (WFP Issue 26 March/April 1997)

UNITED STATES. The Labor Party is calling for a constitutional amendment which would guarantee everyone a job and a living wage. The party in its November publication stated that "There is no way around the slow, bottom-up job of winning millions of Americans to our point of view." The article cites the 1945 Full Employment Act, which was supported by 83 percent of Americans, but was watered down by business lobbying. The Labor Party's strategy is to undertake a huge grass-roots lobbying effort to win the necessary approval of three-fourths of the 50 state legislatures. To get involved locally call (206) 382-1752 or 526-8169. (Labor Party Press)

NORTH AMERICA. A net total of roughly 400,000 jobs have been lost in the US due to NAFTA, according to the Economic Policy Institute. NAFTA took effect in January 1994, and is also responsible for a $25 billion increase in the US trade deficit. Particularly hard hit have been manufacturing jobs for autos, televisions, communication equipment, and computers. The US gained some jobs over Mexico, such as 10,000 jobs from selling electronic components to Mexico. (Northwest Labor Press)

WASHINGTON, D.C. The 40-year-old AFL-CIO News is being replaced by a glossy magazine, America@work, which seems to have an emphasis on hip graphics, but also includes more info on activism than its predecessor, as well as an angrier tone, and practical organizing tips for union activists. The October issue counsels union leaders to not tell their members how to vote (inform them instead about issues), and to resist using insider union jargon when talking with members.

|

|

|

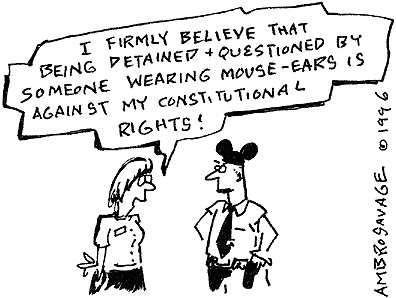

DISNEYLAND. 17-year old Erin Lewellen was detained by security officers at Disneyland because she forgot to check-in her uniform after leaving her job at the Carnation ice cream shop. Park Security and a Disneyland supervisor questioned the girl for two hours, refusing to let her call her mother. Recently, the Orange County Register has interviewed more than 30 people who reported what they thought was abuse by Disneyland security. Seven have filed lawsuits in the past two months. Many said they were held for up to four hours with no access to telephone or bathroom. In three cases, parents alleged that security offered not to seek prosecution of minors if the parents paid $275 in civil damages. California law allows merchants to hold shoplifting suspects as long as is "reasonably necessary" for questioning. (ACLU Newswire)

|

|

|

|

|

Contents on this page were published in the January/February, 1997 edition of the Washington Free Press.

WFP, 1463 E. Republican #178, Seattle, WA -USA, 98112. -- WAfreepress@gmail.com

Copyright © 1997 WFP Collective, Inc.